One of the things I’m always on the alert for while driving along the roads of Ireland is any roadside historical markers.

The Irish have populated their cities and countryside with both simple and ornate markers to commemorate their rich history. Perhaps this is because a foreign government did not allow them to celebrate their history for centuries. And since I’m always the one who’s driving, it’s not always possible for me to look for them, especially on Irelad’s narrow country roads. So, to keep us a bit safer, my wife, Lindy, also serves as a lookout for these monuments.

We were traveling south through the Wicklow Mountains (Dublin Mountains to some) on R-115, also called the "Military Road," on our way to Shillelagh on our June 2014 foray to Ireland.

Suddenly, Lindy noticed a monument to our left, high on the eastern side of the road.

Looking back from the monument toward the "Military Road"

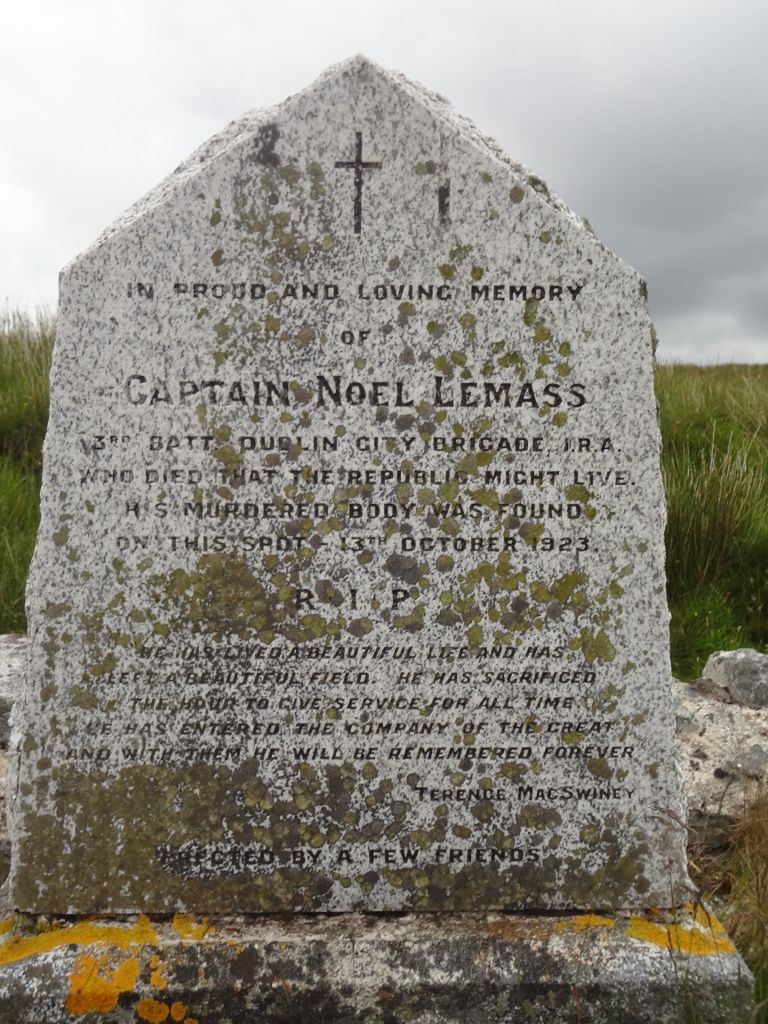

A path of 100 yards or so led to it through the beautiful, serene heather fields leading up the hill. Looking out over the majestic Wicklow Mountains, with a few white balls off in the distance denoting the location of wandering sheep, it would be hard to find a more peaceful spot on Earth. But the monument had little connection to the peace its location presented to those who walked up to it. On the front, it read:

IN PROUD AND LOVING MEMORY

OF

CAPTAIN NOEL LEMASS

3rd BATT DUBLIN CITY BRIGADE I.R.A.

WHO DIED THAT THE REPUBLIC MIGHT LIVE.

HIS MURDERED BODY WAS FOUND

ON THIS SPOT - 13TH OCTOBER 1923

RIP

It then has a quote from hunger strike martyr Terence MacSwiney, and at the bottom, it says, "Erected By A Few Friends."

The date seemed curious, as I knew it was months after the ceasefire that ended the Civil War. The last name, Lemass, was famous in the period. Was Noel related to the well-known Republican of the period and later Taoiseach, Seán Lemass? As is so often the case when we stop at these roadside monuments, it creates questions that make you want to know the full story of what happened there.

As soon as we got home, I began to research the story of Noel Lemass.

The first thing I found out was that Noel was, indeed, Seán’s older brother. In fact, Seán had named his first child after Noel. Seán was one of the founding members of Fianna Fáil in 1926 and was Taoiseach from 1959 to 1966. Seán and Noel fought in the Imperial Hotel during the Easter Rising of 1916 and with the 3rd Battalion, Dublin Brigade Irish Volunteers (later Irish Republican Army) during the War of Independence. Noel was wounded in the Easter Rising and spent time in Dublin Castle Hospital before recovering.

Noel later helped train Volunteers in south Dublin County.He later commanded E Co., 3rd Battalion of the Dublin Brigade. In November 1919, he was arrested by the British for possession of firearms and served a year in prison. As was becoming common among Republican prisoners, he went on hunger strike twice. He was arrested again in May 1921 and spent the remaining months of the war in their custody.

When the Civil War began, Noel and Seán supported the anti-treaty side and were in the Four Courts when it fell. Seán managed to escape, but Noel was captured. Noel escaped, was captured again, and escaped again. He then made his way to England, where he remained during the remainder of the Civil War. He returned after the ceasefire ended or was supposed to end, the Civil War in May 1923.

Noel returned to his job as an engineer at the Dublin Corporation, no doubt thinking that he’d now live out the rest of his life in peace. And perhaps he would have, had his last name been something other than Lemass. Some suffer for the “sins” of their fathers. Noel may have suffered for what someone on the Free State side perceived as his brother’s sins, though it may also been for something he did during the War of Independence. Like most aspects of his death, that remains unknown.

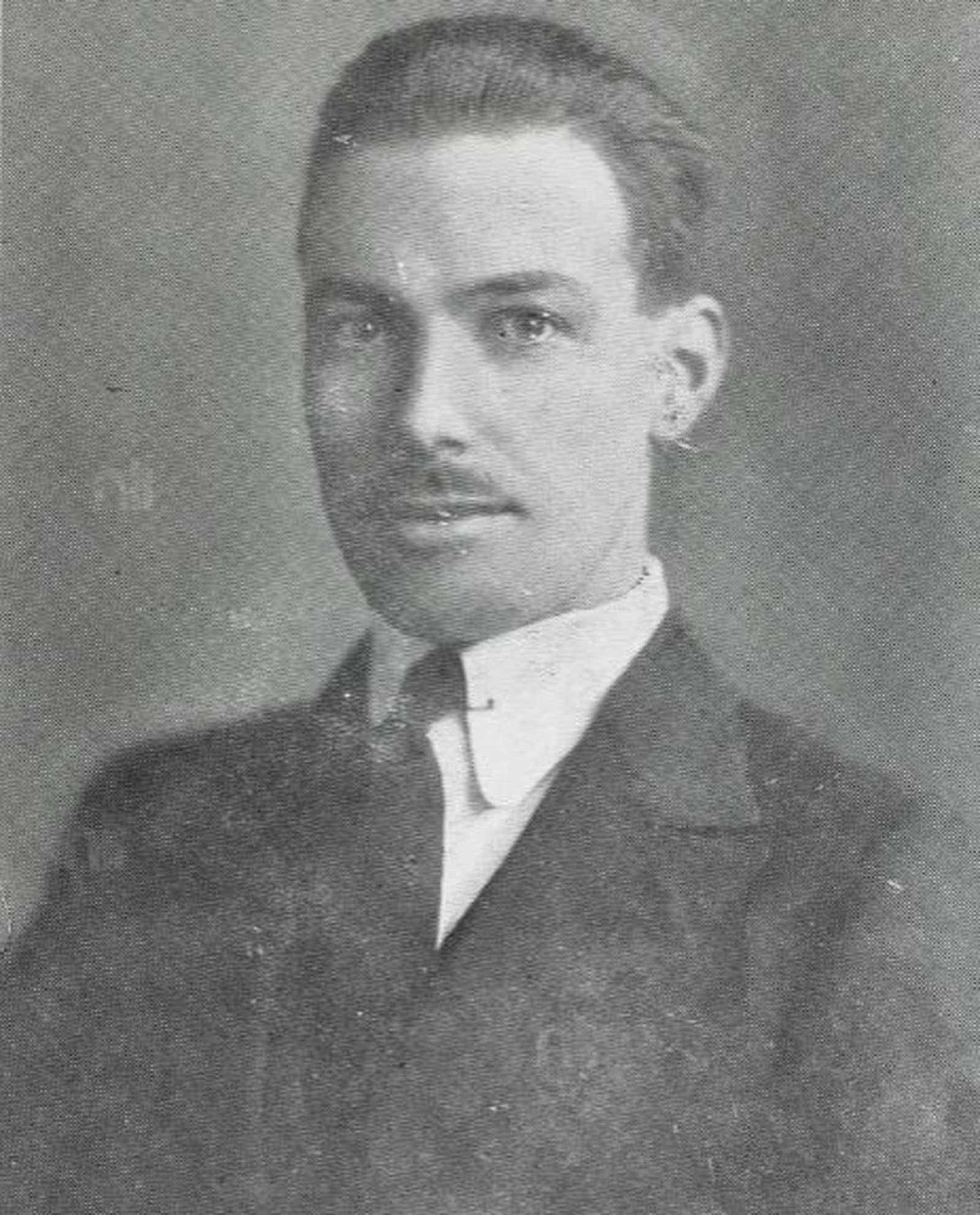

Noel Lemass.

On July 3, 1923, having just finished lunch with friends on Wicklow Street, he was kidnapped outside of MacNeils Hardware shop at the corner of Exchequer and Drury Street. Unless someone who was involved in abducting and killing him over 90 years ago wrote a confession that comes to light sometime in the future, we’ll never know exactly when he died or who killed him.

Civic Guards found his body on October 13 near the spot where the monument now sits, on Featherbed Mountain. He had likely been brutally tortured during his time in captivity, as he had a fractured left arm, missing teeth, and his right foot was missing. He had died from three gunshots to the head.

Like many Irish nationalists before him, Lemass was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery. The Irish Times called the funeral “one of “the largest seen in the city in recent years.” Many well-known Republicans of the era, including Constance Markievicz and Maud Gonne, were in attendance.

Nearly all sources about the murder point to a kidnapping by Free Staters. Supreme Court judge Adrian Hardiman, who died in 2016, did an inquiry for the family and concluded that the evidence pointed to Captain James Murray of the Free State Army intelligence department. Murray had supposedly bragged to someone that he murdered Lemass. He was later convicted of murdering a military police officer. During interrogation about that crime, he said he did so under orders and that “I thought that the job was one of the usual unofficial executions.” However, with the passage of 100 years, it’s unlikely we will ever know the whole story of the murder.

The original monument on Featherbed Mountain had a Celtic cross on top, which vandals destroyed. It was replaced and destroyed again, showing that the memories of those awful days for Ireland are not forgotten. From the 1930s to the 1970s, a commemoration of Lemass’ life was celebrated at the monument.

monument

In October 2023, that tradition was revived with a centennial commemoration at the monument. Unfortunately, they found that the monument had been defaced. Tánaiste Micheál Martin condemned the “desecration” of the stone marker, which had red paint poured over it. It was “very difficult to comprehend why a person or group of people would desecrate a monument like this,” Martin said.

No matter what side one may come down on regarding the issues that caused the Irish Civil War, deaths like that of Noel Lemass can’t be considered anything other than a tragedy, not just for his family but for the nation of Ireland as a whole.

In the name of the lost, the disinherited

All who never came back from the dead

To tell their story, make their peace

And lay me down, in the Featherbed

By a memory-stone, a fouled lair,

Bog-cotton whispering in my ears,

The sound of a car, a light somewhere

In the silences, the years

- From “The Winter Sleep of Captain LeMass” by Harry Clifton

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments