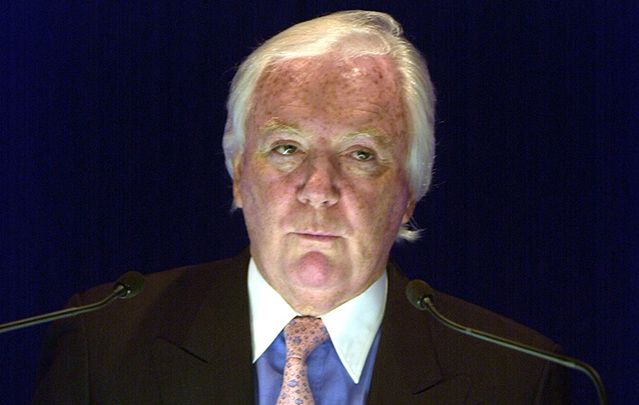

In July 2001, the Pittsburgh Post Gazette headlined a story on the former Heinz CEO and Chairman Tony O’Reilly to the effect that he was "Living large; Anthony O'Reilly rules a global business empire, enchants all those in his sphere and is now addressed as 'Sir'."

The adoring article reflected a lot of the coverage of Ireland’s golden boy at the time. He was simply The Greatest, the business equivalent of Muhammad Ali in Ireland and indeed elsewhere too. For good measure he was a founder of the Ireland Funds, which have raised hundreds of millions since for worthwhile Irish charities and peace process projects.

While O'Reilly was in charge – 1971 to 1998 – Heinz's valuation rose from $908 million to $11 billion. But the first cracks in the Heinz love affair started to appear in the early 90s.

Heinz shareholders had allowed O’Reilly private business interests in Ireland and truth was even Superman would have been stretched by the alarming schedule he kept. Shareholders complained and he stepped down from Heinz in 1999 leaving many with mixed feelings and others believing he was next to God when it came to business. He was in his early sixties by then (he is now 79) with a seemingly glittering new career ahead as entrepreneur and international businessman.

Yet fast forward a decade and a half and the O’Reilly empire was in ruins. Huge gambles like Waterford Crystal, oil exploration, and the Independent newspaper chain had gone awry. He was forced out of his beloved Irish Independent group, which had worldwide holdings, and he was forced to sell off companies like family jewels to stave off the banks. It all culminated in a Bahamas bankruptcy.

Matt Cooper, an excellent editor and journalist in Dublin has written the definitive work on O’Reilly, and while it comes in at close to 564 pages it is still an extraordinary read. The title, “The Maximalist: The Rise and Fall of Tony O’Reilly,” pretty much explains the context.

I will voice some disagreements first, mostly with the Irish American sections. Cooper, like many in Ireland, view O’Reilly and his work with the Ireland Funds as blocking the work of the IRA-supporting Irish Northern Aid organization. The Funds took many would-be donors to violence from Noraid he says.

Not true. The fund did marvelous work bringing Irish American business leaders together and aiding with the peace process when it happened, especially bringing leaders on all sides to South Africa for critical meetings. But they never had the slightest impact on Noraid.

As FBI files that showed up in numerous IRA court cases I covered showed, the main actors in Noraid were overwhelmingly wealthy emigrants from Ireland, usually from the North. The best known leader, Martin Galvin, ran a small law practice in The Bronx.

The best known gunrunner was George Harrison, a Mayo man who once convinced a jury the CIA made him do it. He walked. George was so much to the left he fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Noraid people were hardly likely to be impressed with the Ireland Funds goals.

Likewise, I disagree with Cooper's description of O’Reilly as a constitutional nationalist. Constitutional nationalists do not take British knighthoods or allow the leader of constitutional nationalism, John Hume, to be regularly savaged in his newspapers as Hume was by the Sunday Independent. Neo Unionist is a far more applicable appellation.

Those quibbles aside, the Cooper portrait is multifaceted and deeply researched. He reveals there were many dark shadows in O’Reilly’s otherwise charmed life. O’Reilly found out at 15 that his parents weren't married, that his father John had left his wife for Tony’s mother, Aileen.

Quite how that reverberated throughout O’Reilly’s life at a time in Ireland where such extra marital situations were not just frowned on but cruelly opposed, often publicly, is one of Cooper’s lines of investigation.

Did the hectic lifestyle, the constant seeking of attention and courtiers, the flamboyance and the charm, the much criticized taking of a knighthood from the queen stem from the massive insecurity of that childhood secret?

It seems possible. If so it certainly drove him like a demon. There is no doubt he was an extraordinary talent at whatever he turned his hand to.

He was on the Irish rugby team at 17, made the Lions team made up of the best players in Britain and Ireland, and became a young red haired God during a Lions tour of South Africa where he revealed extraordinary potential.

His rugby career subsequently sputtered through injuries and his workaholic habits (rugby was still an amateur game), but he found himself at a very young age making a hugely significant discovery as marketing head of Bord Bainne, the Irish Dairy Board, that Irish butter subsequently packaged as Kerrygold could become an enormous international hit. He was right and to this day Kerrygold is one of the best known Irish exports.

His extraordinary work with Erin Foods, his next employer, led to a deal with Heinz, the American giant, who quickly recognized the young man’s marketing genius and incredible energy.

He found himself in his late thirties running one of the major corporations in America, and successfully too.

Amazingly, the company allowed him continue his Irish interests and it made for a hectic time back and forth across the Atlantic. It is obvious from his Heinz success that O’Reillys greatest skill was in management and from his subsequent business failures that entrepreneurship, or lack of it, was what led to his downfall.

He carried off one amazing coup, buying the Irish Independent, Ireland’s leading newspaper title, for a little over $2 million, and turned it into an international empire with newspapers in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, The Independent in Britain, and numerous regional papers in Ireland.

If O'Reilly was slow to see the internet boom shaping up, he was not on his own. One can hardly blame him for being caught unawares, like every journalist and proprietor was, with how devastating the impact was on the print market.

O’Reilly lost out on his Independent titles to a takeover bid by Denis O’Brien, his closest equivalent, wealth wise, from the next generation. The O’Reilly papers had been incredibly negative to O’Brien, who finally lost patience and out-maneuvered O'Reilly, who by that time was so highly leveraged that he lacked the funds to fight back.

O’Brien cited the attacks on John Hume as one of his chief beefs with the paper.

Cooper points out repeatedly that O’Reilly borrowed and leveraged far too much in most of his companies and then became a casualty of the perfect storm when the world economy almost collapsed.

Incredibly, a man who bestrode the world as one of Ireland's richest men, worth over $3 billion, was reduced to horrific debts as the storm raged on.

Several banks, notably Allied Irish, itself kept afloat by $21 billion from the Irish taxpayer, gathered like vultures around O'Reilly and very publicly revealed his financial shortcomings.

For his service alone to Ireland, as Cooper says, he deserved much better. But as Waterford Crystal went to the brink of collapse, his exploration for oil off Ireland's shores failed and his newspapers got taken over. O'Reilly, a wounded lion in winter, was there for the taking.

He declared bankruptcy in the Bahamas thereby giving himself some respite.

At 79 now, O’Reilly’s glory days are gone. But Cooper imagines a more generous and complete picture of O'Reilly emerging in the future than just a man who made and lost a fortune.

This book will certainly help balance the scale.

Comments