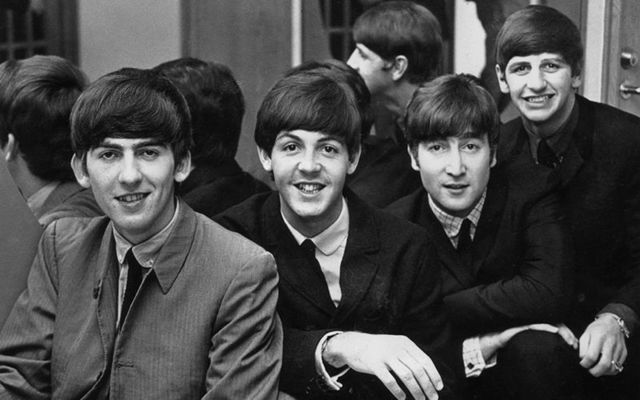

An extract from poet Gerald Dawe’s memoir about growing up in Belfast during The Beatles era.

I was eleven when The Beatles started their inexorable rise to global fame in 1963 and eighteen when they split up. So there’s a slight hitch in the way one thinks about that past because it isn’t separate or ‘other’; it is, as Stewart Parker, Irish playwright and one-time ‘High

Pop’ columnist for The Irish Times, had it, ‘bred in the bone’, remarking in 1976 on the re-release by EMI of all The Beatles’ singles – ‘it is a new and sobering experience, to see the music of your adolescence revived as though it were something historical and unfamiliar rather than something bred in the bone’.

To think aloud about Rubber Soul or Revolver or Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is to take in the time when one first heard the albums, and with whom and where. An emotional mosaic unselfconsciously surfaces through the lyrics and the music, along with the unmistakable merging harmonic of the voices. It all adds up to an indefinable atmosphere of what it felt like once to hear the words that one knew, we knew, by heart. Because The Beatles’ songs were all known by heart.

This article was originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes magazine. Subscribe now!

It amazes me to this day just how many songs, moves and air-guitar moments reside in all my sixty-plus-something friends’ heads and gestures half a century on. We watched the at-times snowy black and white TV screen or listened, as pop-pickers, to the radio (and transistors) and obsessed over LPs, singles and EPs in the record shops of Belfast’s city center and hung out in the casbah known as Smithfield, before taking the step into one of the many clubs and dance halls that were such a feature of downtown Belfast before the desperate days of the Troubles.

In passing, it might be worth noting that when Rubber Soul came out at the beginning of 1965, that year also marked an auspiciously hopeful – albeit short-lived – moment in local history with the first meeting since December 1925 of an Irish Taoiseach, Sean Lemass, and the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O’Neill. The meeting took place on 13–14 January. Not that it caught the imagination of the teenagers with whom I was hanging out in downtown Belfast.

"Looking Through You: Northern Chronicles" by Gerald Dawe.

Listening to The Beatles was part of listening to a widening circle of groups for my part of that sixties generation – slightly too young to see The Beatles perform live in the Ritz cinema in 1963 or the following year in the King’s Hall; listening to their albums was what we did. Indeed, I have a notion – which could well be completely wrong – that this is what we mostly did with The Beatles’ music, throughout their ascendency and into the post-Beatles decade of the seventies and beyond: listen and not dance to it.

For though dancing was such a part and parcel of our social life, there were few enough Beatles songs that I can recall actually dancing to other than with the slower ‘smoochier’ numbers. This was distinctly different to the free-forming individualistic moves that accompanied The Rolling Stones’ records, or the shifting macho showings-off to all the excellent R&B bands that performed in Belfast, as well as the personal favorites of my own cohort of friends, such as the Small Faces, who got everyone going, even at their so-called sit-down ‘concerts’, from the very first beat of Stevie Marriott’s pouting, knock-kneed skip across the stage of the Ulster Hall. Magic.

* "Looking Through You: Northern Chronicles" by Gerald Dawe with photographs by Euan Gebler, is available now.

Comments