An extract from the book "Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland" by Cormac Moore.

Partition was seriously considered as a way out of the impasse between Irish nationalists and unionists for the first time in 1912 with the introduction of the third Home Rule Bill. Many options were considered thereafter relating to the kind of partition, the area to be partitioned and for how long. A number of attempts to solve the Irish question were made, up to and during the First World War to reach a solution, all falling short.

The concept of creating two Irish parliaments was first introduced by the decisive Government of Ireland Bill in 1919. It was opposed by almost all, including Ulster unionists, who had never asked for devolved government. Eventually, many within Ulster unionism realized the benefits of having their own government and voted in favor of the bill. As the bill was making its way through the houses of parliament, the British government was fighting a war with Sinn Féin and its military wing, the Irish Republican Army (IRA). The Government of Ireland Act was totally rejected by Sinn Féin, by almost all within the south and west of Ireland and by one-third of the population designated to belong to the territory of Northern Ireland.

With very little templates to work off, Sir Ernest Clark, assistant under-secretary for Ireland, located in Belfast, was primarily responsible for ensuring that a functioning government and administration existed once Northern Ireland came into being in May 1921. Since the Act of Union of 1800, Ireland had been administered as a separate entity with almost all government and non-government bodies headquartered in Dublin. The breaking up of bodies into two was a gargantuan task, often met with resistance.

This article was originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes magazine. Subscribe now!

Sinn Féin and the nationalist minority in the north boycotted the northern government and its institutions. From its rise in popularity after the Easter Rising to the truce of July 1921, Sinn Féin had no clear policy on how to deal with the unionist minority in the northeast of Ireland. The negotiations with the British in late 1921 forced Sinn Fein to address the issue of partition realistically for the first time. The resulting Anglo-Irish Treaty included a boundary commission to determine the size of Northern Ireland. Sinn Féin naively believed this would transfer much of the northern territory to the Irish Free State. Much to the shock and bewilderment of many nationalists, the boundary commission report was shelved in 1925, with the status quo being retained.

Sectarian violence engulfed the north from 1920 to 1922, particularly in Belfast where some of the most brutal disturbances throughout Ireland occurred. Over 550 people were killed violently during this period. Heavily armed loyalists, aided by the British, were pitted against the IRA, aided by Michael Collins’s provisional government during the first half of 1922 in a civil war in all but name. The start of the civil war in the south from June 1922 intervened to ease the pressure on the beleaguered north.

Two new justice systems for Ireland were created under the Government of Ireland Act, which perfectly illustrated the complexity and confusion surrounding partition. Whilst the Irish Free State was presented with justice systems of the past (British and the homegrown Dáil Courts), the northern judiciary had to start from scratch, with no courthouse, no staff, even no books. The one area where there was cooperation, the education of barristers from all parts of Ireland at King’s Inns in Dublin, only lasted for a short period, with both jurisdictions eventually diverging in all aspects of law as in politics.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

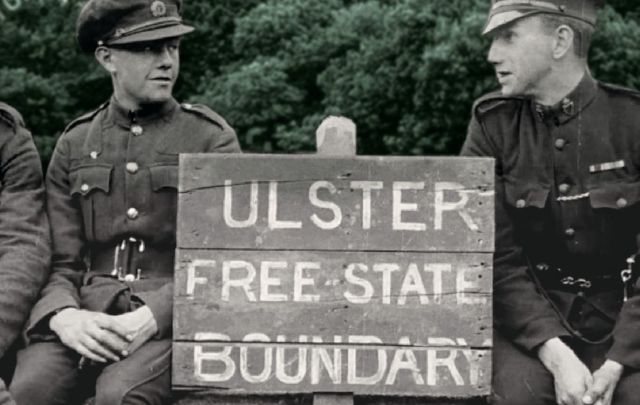

Arguably, the cementing of partition came with the imposition of customs barriers on the border in 1923, a decision made by the Free State government. This decision, following on from the Belfast Boycott of 1920 to 1922, resulted in psychological and physical divisions, some that had never existed before.

Despite the upheavals that led to partition, many organizations and groups continued on as before. With no obligation to divide based on the political division, most organizations, trade groups and charities that were all-Ireland bodies before 1921, remained so afterward. Most religious organizations remained all-Ireland entities, regardless of the central role of religion to the Irish question. They did so under very changed circumstances, though, having to operate within two widely different jurisdictions. This was most clearly demonstrated through the issue of education within both states, where the major religions played a pivotal role. Divisions in education that existed before, were worsened by partition. Both jurisdictions adopted very different approaches to education, the north looking to democratize it whilst the south looked to Gaelicise it. A striking example of Irish nationalism’s non-recognition of the northern jurisdiction was the payment of Catholic teachers based in the north by the provisional government in the south.

The labor movement consisted of a divergent group of people; Protestants and Catholics; nationalists and unionists; and internationalists. The political division of the island led to great pressures on the movement. Many trade unions and the Labour Party looked to retain union by focusing on areas of common interest and by offering degrees of autonomy to northern members.

This article was originally published in Ireland of the Welcomes magazine. Subscribe now!

The disruption caused by partition was clearly seen through changes required to parts of Ireland’s infrastructure and services. The creation of the border impacted greatly on railways, roads, fisheries and postal services, as well as many other areas. Changes required to the Irish infrastructure and services, to accommodate the creation of two jurisdictions affected people more on a day-to-day basis than almost anything else.

All sports were affected by partition, some more so than others. Many sports such as rugby, cricket, horse racing, hockey and boxing remained or became all-Ireland bodies after partition. Football and athletics stand out by being partitioned along political lines. Those that are governed on an all-Ireland basis navigated the difficult political terrain by accommodating diverse interests and compromising on areas of symbolic importance such as flags, anthems and emblems.

Great uncertainty surrounded Northern Ireland’s status for many years after its birth, with this uncertainty feeding into decisions made by many bodies, political and non-political. A unique feature of the partition of Ireland, compared to other jurisdictions, were the number of organizations across most spheres of Irish life who were allowed to, and chose to, ignore the new international frontier, and continue on as they had before, as all-Ireland entities.

* "Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland" by Cormac Moore is available on Amazon.

Comments