Editor's note: In May 2022, our sister publication, Ireland of the Welcomes, celebrated its 70th anniversary. To mark the occasion, we dipped into our decades of archives and found incredible articles like this and others written by famous Irish figures such as Patrick Kavanagh, and the beloved Irish artist, Paul Henry, and renowned photographer, John Hinde. Here, in a 1952 article, author Brendan Behan revels in the County Kerry accent and its characters.

At Listowel the man in the pub told us to wait while he went for a poet, left his goods in our custody for a quarter of an hour and came back with John, a young chemist’s assistant. The publican ordered him to get out there on the floor and give us a good one. This John refused to do, but once the intercession of his employer he showed us some of his verse.

It’s not every place a publican will run out in the street for a poet, in the full confidence of finding one. That’s Kerry for you.

Take the opposite end. Stand up on Slea Head. The heart will strain after the eye, to the far edge of the world, and a lone eagle in the last ray of the sun. The huge, high arms of the peninsulas, Dingle and Iveragh, muscled and mountainous, stretched out towards the glory of God, and the Blaskets, almost in their grasp, where the smoke rises from the last chimneys between here and America, and the last of the fishermen sit at the turf-fire of an evening, telling stories that Homer heard from his grandmother.

Robin Flower came over from the British Museum and stayed with them so long and so often that he was mourned, like a neighbor’s child, when the news of his death was brought to the islands from far away London.

But a good story is never lost, in death or time. “Où est la neige de l’année passée?” quoted Robin to the King of is island and the people gathered one night in the kitchen.

“What is that,” asked the King in Irish, “is it the Gaelic of the West or of Ulster?”

“It’s French,” said Flower, translating it into Irish: “Ca bhiuil an sneachta gheal bhi ann anuiridh?”

“Right,” said everyone together, “we have that here: ‘where is the bright snow from last year?’ “

Said Robin Flower: “The man that said that in French was a poet.”

“I’d have no doubt he was,” said the King, “and a good one. And I wouldn’t be surprised if he had it before us, for the French are a great people.”

“Francois Villon was his name,” said Flower, “and he was sentenced to be hanged.”

“Many a good poet’s case,” said the island poet, that could write a verse to cut the ground from under you, and scatter the ashes of your ancestors, if you wouldn’t stop on your way to cut turf or dig potatoes, to listen to his latest fifty lines. “Wasn’t Pierce Ferriter, a poet and a nobleman, hanged from the walls of his own castle over across there,” turning in his chair and pointing the stem of his pipe in the direction of the mainland, “for the love of Ireland?”

“This French poet,” said Flower, “was sentenced for the love of women and a great interest in other people’s money. But the King let him go, on account of his uncle being a priest and he wasn’t hanged at all in the heel of the hunt.”

“Praised be the King of Graces,” said the island poet.

“Amen, amen, oh God,” the people added quickly, to keep the right side of him and his satirical muse far from their own half-door.

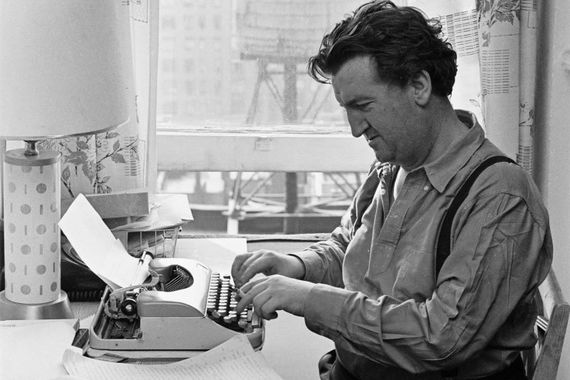

Irish author Brendan Behan.

In Tralee, they debated football, politics and the genealogies of great clans. These heirs of old nobility sat and drank pints of stout in the back smug, whose fathers held court in castles and gave the bard a hearing over the wine.

“And aren’t we every bit as comfortable?” said Dickeen, and continued his story of a faithless wife, killed in a hunt, who after death, for some reason, continued to eat her own shoulders.

The principal leader, of the area, in the guerilla times, gave details of his plan for a memorial to fallen comrades.

“We will have for a bae, a big green mound, and on top of that, an Irish rock, from a local quarry . . .”

“And,” asked Dickeen, “what other sort of a rock would you expect to get in a local quarry?”

“. . . The Maid of Erin on the top of that, and on top of that again, a fallen soldier of Ireland, his head in her lap, his revolver still smoking.”

The Pikeman statue, in Tralee, County Kerry.

“In Irish granite?” asked Dickeen. “Why, with one thing on top of another like that, John Joe, ‘tis not a sculptor you’ll be wanting at all, but a juggler.”

In Caherdaniel, you’ll be bedded like a prince and fed like his father for a half nothing and the quarter of that again, if you can sing a song.

Down the road is the beach of Derrynane, and the old home of The Liberator, Dan O’Connell. Many’s the time he must have galloped that two miles in the night, and the roar of the Atlantic growing faint behind him, while he rode on to the old coach road over Coomakista, towards Cork Jail, and the condemned cell, and the anxious face at the window, watching the West.

Derrynane Beach, Caherdaniel.

Micheál is there and his fine house the heart of hospitality, where you might meet anyone, a lord, who is also a poet, with a Tommy, a hunter before the Lord, with gun and line, discussing spinners and the best ways of getting bass and pollock to bite them. I didn’t know much about this, so I listened to the man of the house telling of the last great fight of the Fianna on the white strand of Ventry opposite, and heard read an old poem from his manuscript collection, his wife contradicting on the origins of it, while the maids made bold to join the argument.

I drank a bottle of champagne at Killarney. The others had one apiece, too. I recommended it on the strength of my being an old client (and the only Caucasian) of Les Clochards café in the Place Mauber, since closed by the police. I was also celebrating the lakes. The only way to do it. All the songs have been already written. Like champagne, it is vulgar to praise that beauty that squeezes the heart at the first sight.

Killarney National Park.

I talked to a man and so as not to seem uppish in my Gordon Rouge, told him that we didn’t always drink it.

“No,” he said, “but only when your friends have done well at the races.”

They were bookies all right, but I asked how he could tell that they were.

“I know friends of yours at Tiernaboul, and know that you wouldn’t have the wit for it– God help you, and as for your friends, haven’t I passed thousands through my hands?”

So he had too, from Saratoga backwards, and come home at last, with but enough to live on.

“Amn’t I lucky,” he laughed, “to have that much without working. And living in the sight of the lakes of Killarney?”

“I wouldn’t have thought you’d have thought about it that much, and you born here,” I said. “I was afraid to say I thought them that beautiful in case you might smile and say you were listening to that every season in the year.”He looked at me and said, slowly and very earnestly.

“A mhic, the day God made Killarney He was in good humour.”

Ballybunion is stylish and the strollers on the Atlantic Walk are a cut above buttermilk, holiday frocks and gents drapes– but it has a good heart behind its smooth exterior, and it beats strong till late in the evening.

Ballybunion Beach.

As the American said to the Garda Siochana: “And what time do the pubs shut round here, officer?”

“Fairly late in September, sir.”

The summer sun goes highest at Killorglin, at Puck Fair, when the goat reigns Lord of all, in his box forty feet over the main street, nibbling quietly a rib of the royal lettuce, and watching with cold eye, the antics of his subjects down below. Melodeon and mouth-organ and the tinkers swinging wild in a jig in the moonlight.

“Laughing, love and life swung round,

And the drumbeat lifts her high from the ground,

And the roar goes up, and her screech is drowned,

At Puck Fair in Killorglin.”

Are you planning a vacation in Ireland? Looking for advice or want to share some great memories? Join our Irish travel Facebook group.

Or as Joyce said in "Finnegan’s Wake", regarding this matter of Kerry, and the high mountains and round the Atlantic, and the fuchsia wild as a weed, and red by the roadsides, lining the length of them, and the silver beaches, and the high Castilian brogue of the people, and the mad delights of Puck, and the peace of God at Innisfallen:

“Come all you sweet nymphs of Dingle beach,

To cheer from Brinabride from Sybil surf-riding,

In her curragh of shells and daughter of pearl

And her silvery moonblue mantle round her,

Crown of the waters, brine on her brow,

She’ll dance from a jig and jilt them fairly.

Yerra, why should she bide with Sig Sloomyside,

Or the grogram, grey barnacle gander?”

Why, indeed?

* Brendan Behan was an Irish poet, playwright, novelist, and memoirist. He was born on February 9, 1923, in Dublin, Ireland, and died on March 20, 1964, in Dublin as well. Behan is best known for his play "The Quare Fellow" (1954), which depicts the lives of inmates in Mountjoy Prison in Dublin. The play is renowned for its dark humor and exploration of social and political themes.

** This article was originally published 71 years ago in our sister publication Ireland of the Welcomes, 1952.

Comments