A couple of years back, I asked a roomful of college freshmen and women to name the world’s most famous living Muslim.

“Barack Obama!” stage-whispered one wag.

“Osama Bin Laden,” shouted another.

Eventually, after some muttering and perhaps even surreptitious Googling, somebody offered Muhammad Ali.

“Oh yeah,” piped up a voice at the back, suddenly feigning knowledge of the subject.

“He’s that boxer who bit the other boxer on the ear.”

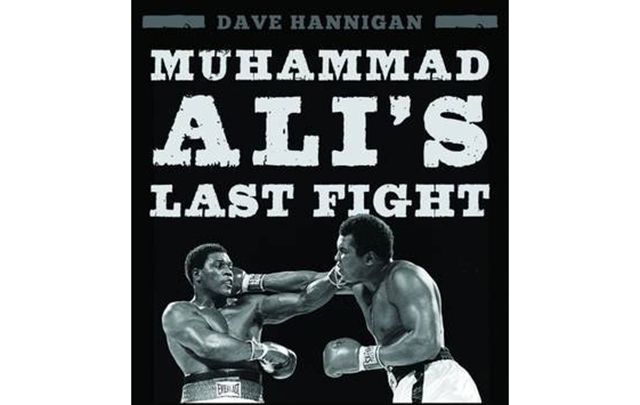

A few days before Ali died last June, I signed off on the proofs of “Drama in the Bahamas – Muhammad Ali’s Last Fight,' a book about his final bout against Trevor Berbick in December, 1981.

It was the culmination of fifteen months’ work.

When people asked me why devote so much time to a long-forgotten entry on the most storied resume in sport, I’d reel off the above anecdote.

Two generations have come of age since Ali fought his last. Somebody has to educate these millennials about Ali’s wider cultural significance.

Of course, that reasoning rings a little hollow.

Read More: The Greatest, Muhammad Ali, was very proud of his Irish roots

If you type Muhammad Ali into Amazon there are almost 17000 titles about him, or in which he is heavily featured.

That’s way too many books even for the greatest.

Since perhaps a dozen of them are also among the finest non-fiction works available, the canon is already rich enough for anybody seeking enlightenment about why Muhammad Ali still matters.

In truth, my justification for adding to the slush pile was way more selfish than spreading the gospel or simply telling what I think is a fascinating untold story about the final moments of Ali’s fistic career.

I also wanted to immerse myself in the world of Ali because, for a writer, there is no more enjoyable place to spend time.

I know this because I’ve been there before.

In 2001, I wrote a book about Ali’s fight in Croke Park and the magical week in Dublin surrounding that bout.

I have never had more fun on professional endeavor.

Until now.

See, when you call somebody up to talk about their experience with Ali, whether fleeting or long-standing, you are asking them to revisit one of the genuinely epic moments from their own life.

They are thrilled to take the call or answer the email, excited to reminisce about that cameo when they too were, however briefly, touched by greatness.

Then, when you delve into the newspaper archives, snaffle fraying old magazines on eBay and sift through the available literature, you are exposing yourself to the very finest writing and photography.

Which can be good and bad.

The difficulty when trying to recreate the story of the Berbick fight is that Hugh Mcllvaney’s poignant contemporary report on the contest for The Observer newspaper is near enough a work of journalistic art.

YouTube offers other dangers because here, truly, was a life lived in front of the cameras.

You might set off on a quest to find televisual evidence of Ali slurring his words in a 1981 television appearance and suddenly you are knee-deep in a particularly demented episode of (talk show) Parkinson with comedian Freddie Starr using the boxer as his comic foil.

Read More: Exclusive: Liam Neeson on the greatest of them all, Muhammad Ali

Tremendously entertaining, but before you know it you are off down the rabbit hole, half the night is gone and there isn’t a sentence in the house washed.

The joy of the journey is you never know where the research will take you.

One minute Ali is in Las Vegas fighting to keep his boxing license, the next he’s in London promoting “Freedom Road,” an NBC television movie in which he plays an ex-slave turned U.S. senator.

He pops up in Portland, Oregon talking to a freeze dried food company about initiatives to feed the hungry in the Third World, then he’s name checking the hunger strikers in the Maze Prison as an inspiration at a Chicago press conference.

Running my finger along the index, among the entries are Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Leonid Brezhnev, Deng Xiaoping, John Travolta, Muammar Gaddafi, Liam Neeson, Eddie Murphy and Bobby Womack.

When you are charged with knitting together a narrative with a cast of characters that rich and diverse, you gain heightened appreciation of the term passion project.

Not to mention you stumble upon quotes that remind you of Ali’s enduring relevance.

The same week Donald Trump was ludicrously claiming there were no great Muslim athletes, I found Ali trying to sell the Berbick bout as a sporting jihad: “I am a warrior of Islam. This is Holy War. I am fighting for Allah. Look what I’ve accomplished. People don’t think twice about Muslim names. Look at all the ballplayers with Muslim names.”

In the moments after losing to Berbick, Ali was stretched on a locker-room table looking every aching inch a man a few weeks shy of 40.

Then a journalist asked if in retirement he might become a goodwill ambassador to improve relations between Gaddafi and the White House.

Who else, in the waning minutes of his sporting life, could spark a geo-political discussion about concerns Libya was bent on assassinating Reagan?

One more bizarre measure of the man.

One more illustration of why many had tears in their eyes watching him suffer unnecessarily in the ring the night the curtain finally, thankfully, belatedly, came down in the Caribbean.

Between this book and “The Big Fight” I’ve now spent 30 months of my career researching and writing about Muhammad Ali.

Thirty months and not a single minute of it ever felt like work.

Read More: Rare footage of when Muhammad Ali did an Irish tourism promotion (VIDEO)

---

This article first appeared in the Irish Echo. For more stories, visit their website.

Comments