Seen by most as a fun-filled 1960s romp, "A Hard Day's Night" is in fact a Beatles movie with an anti-British undercurrent filled with pro-Fenian rhetoric.

I have found the Fountain of Youth. It’s called watching The Beatles in "A Hard Day’s Night."

Not only do you get to hear several of their early ’60s hits, but you get to laugh at all the absurdities of the world through the eyes of youth. It is a comedy in the spirit of the Marx Brothers and with a wink of the eye casts a cold stare against the Cold War, future stupid wars, austerity, and the general political bulls--t of the time—which is the general political bulls--t we’re all still living through today.

This is a subversive film, very dangerous in its own way. Ironically, it came out the same year, 1964, that gave us "Dr. Strangelove," the ultimate subversive film and maybe the best statement of the century on the stupid politics of the century. It’s like the kids of the time—and I was one of them—are telling the world through this Beatles flick that we are sick and tired about listening to the politicians and all their fearmongering about nuclear bombs, communism, and their everlasting Cold War.

There is a scene on the train at the beginning where they are trapped in this compartment with a regular commuter—armed with bowler hat and ubiquitous umbrella—the symbolic backbone of Britain. First, he closes the window. The boys protest. Then they turn on their radio nice and loud and he turns it off. “I fought the war for your sort!” he finally says.

And Ringo has the perfect reply, “I bet you’re sorry you won!”

Fenians Unite!

There is also something else that delighted me about "A Hard Day’s Night"—it's wonderful anti-British, pro-Fenian rhetoric. This is manifested in Paul McCartney’s supposed grandfather, John McCartney, played by Dublin-born actor Wilfrid Brambell, perhaps best known for his appearances on "Steptoe and Son" on British television. He’s a disruptive, scheming, lecherous old bastard capable of anything. People are always saying what a “clean” old man he is. Actually, he is the opposite—a dirty old man.

Wanting to go to a casino where sin is sure to be on duty, he swaps his clothes for the tuxedo of the room service waiter and is soon bending over a gaming table. He spies a well-endowed young woman and comments, “I bet you’re a great swimmer!”

He is known in the casino as “Lord John McCartney, a millionaire Irish peer. Filthy rich, of course!” After losing nearly £200 pounds, he is rescued by the boys.

Grandfather McCartney is rounded up by the police for selling forged Beatle autographs and goes right after the poor police desk sergeant: “Ya ugly great brute, ya got sad-ism stamped all over your bloated British kisser!”

Not to be outdone, he invokes an Irish weapon of war: “I’ll go on hunger strike…I’m a soldier of the Republic!” He then sings several choruses of “A Nation Once Again”!

The boys do some anti-British mocking of their own, led mostly by John Lennon. While Lennon is being measured by a tailor he turns around, scissors in hand, and cuts the measuring tape, declaring regally, “I now declare this bridge open,” a clear mocking of the Royal Family and their civic contributions of the day—ribbon cutting.

Lennon also recreates the sea battles of World War II in the bathtub with a toy submarine, alternately singing “Rule Britannia” and “Deutschland Uber Alles.” This is a long way from the heroic British naval films of the day such as "Pursuit of the Graf Spee" and "Sink the Bismarck."

Then there’s Lennon dressed up as a disheveled Abe Lincoln admonishing: “This older generation is leading this country to galloping ruin!” The younger generation will be heard!

A tip of the hat should go to screenwriter Alun Owen, who received an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay. Owen was from Wales, but his mother was of Irish descent, perhaps explaining the many nationalist proclamations in the production.

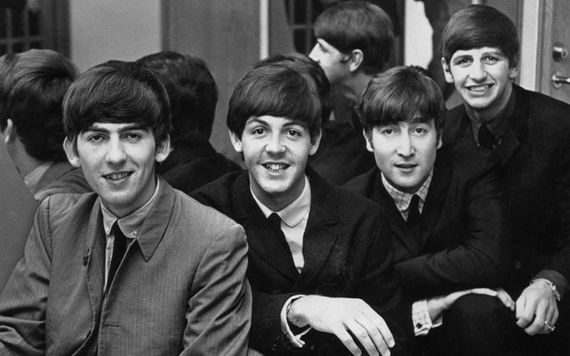

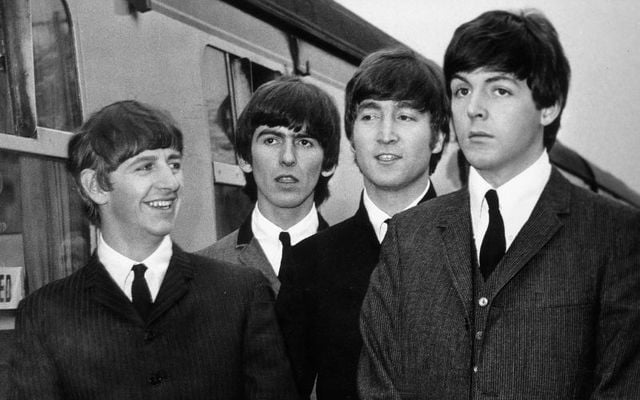

The Beatles. (Getty Images)

How Irish were the Beatles?

“We’re all Irish,” John Lennon famously declared when the Beatles toured Ireland in the fall of 1963.

There was, indeed, a lot of Irish blood in The Beatles. The guy with the most Irish name, Paul McCartney, was the product of a union between Jim McCartney and his wife, Mary Patricia, née Mahon. McCartney’s maternal grandfather was born in Ireland and was Catholic, while he had a Protestant great-grandfather who was also born in Ireland.

John Lennon’s father was a merchant seaman of Irish descent. “I’m a quarter Irish or half Irish or something,” Lennon declared in 1971, “and long, long before the [Northern Irish] trouble started, I told Yoko that’s where we’re going to retire, and I took her to Ireland. We went around Ireland a bit and we stayed in Ireland and we had a sort of second honeymoon there. So, I was completely involved in Ireland.” In fact, he bought an island off the west coast of Ireland for his retirement plans.

Even Ringo Starr, who was born Richard Starkey, had some Irish blood traceable to County Mayo.

Maybe the most Irish of all The Beatles was George Harrison. His mother was an Irish Catholic and he often visited Ireland to see his family who lived on the Northside of Dublin.

So it seems the infamous “British Invasion” was led by a quartet of Irish Wild Geese musicians!

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

The Troubles brings out the Irish in the Beatles

When the Troubles broke out in the North in 1969 two of The Beatles went to work to protest British occupation of Ireland.

Lennon, collaborating with Yoko Ono wrote “Sunday, Bloody Sunday” in response to the British murdering 14 Irishmen in Derry on January 30, 1972.

Hear it here - "Sunday, Bloody Sunday" by John Lennon:

The lyrics are bitter, virulent, and devastating:

You anglo pigs and scotties

Sent to colonise the North

You wave your bloody Union Jacks

And you know what it's worth

How dare you hold to ransom

A people proud and free

Keep Ireland for the Irish

Put the English back to sea.

It continues:

Well, it’s always Bloody Sunday

In the concentration camps

Keep Falls Road free forever

From the bloody English hands

Repatriate to Britain,

All of you who call it home

Leave Ireland to the Irish

Not for London or for Rome

Lennon also wrote “The Luck of the Irish” for his 1972 album, “Some Time in New York City,” again collaborating with Yoko. The title is a play on the oxymoronic phrase about the Irish. Lennon sees that there is no “luck” in famine, occupation, disease, and occupation.

The chorus is devastating:

You should have the luck of the Irish,

You'd be sorry and wish you were dead

You should have the luck of the Irish

And you'd wish you was English instead

Then Lennon really goes to work:

A thousand years of torture and hunger

Drove the people away from their land

A land full of beauty and wonder

Was raped by the British brigands

Goddamned

Goddamned

The song continues:

Why the hell are the English there anyway?

As they kill with God on their side

Blame it all on the kids and the I.R.A.

As the bastards commit genocide

Aye, aye

Genocide

John and Yoko were not the only ones to take on the English. Paul McCartney wrote “Give Ireland Back to the Irish.”

Hear “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” here:

Just like Lennon collaborated with Yoko, McCartney worked with his wife Linda on the song. Basically, the song wants to know what the hell Britain is doing in Ireland after nearly 800 years:

Give Ireland back to the Irish

Don't make them have to take it away

Give Ireland back to the Irish

Make Ireland Irish todayGreat Britain, you are tremendous

And nobody knows like me

But really what are you doin'

In the land across the sea?

It continues:

Tell me how would you like it

If on your way to work

You were stopped by Irish soliders

Would you lie down, do nothing

Would you give in, or go berserk?

It continues:

Great Britian and all the people

Say that people must be free

And meanwhile back in Ireland

There's a man who looks like me

And he dreams of God and country

And he's feeling really bad

And he's sitting in a prison

Should he lie down do nothing?

Should he give in or go mad?

These lyrics so outraged the British that the song was banned in Britain but became a hit in Ireland.

So the next time "A Hard Day’s Night" is on TV, remember that the madcap Fab Four British musicians are actually Fenians in disguise.

*Dermot McEvoy is the author of "The 13th Apostle: A Novel of Michael Collins and the Irish Uprising" and "Our Lady of Greenwich Village," both available in paperback, Kindle, and Audio from Skyhorse Publishing. He may be reached at [email protected]. You can follow him on Facebook.

* Originally published in May 2019. Last updated in 2024.

Comments