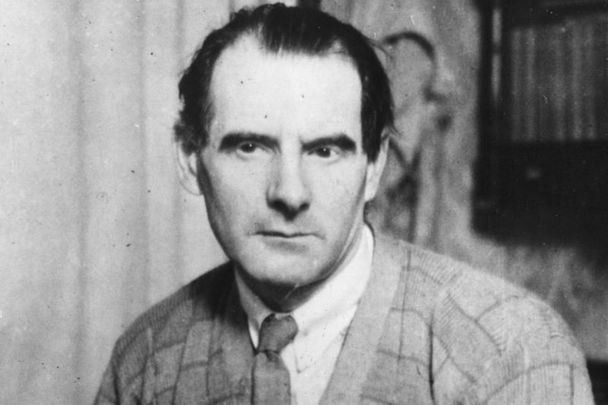

Editor's Note: On September 18, 1964, Sean O'Casey, the beloved Irish playwright famous for plays such as "Juno and the Paycock," "The Plough and the Stars," and "Shadow of a Gunman," passed away. Today, we remember the literary treasure and his legacy.

I heard the song, "Red Roses For Me," recently. Written by Sean O’Casey in 1943 for his play of the same name, it unleashed a wave of memories.

The commercial failure of the play caused O’Casey to veer away from theatre and write an amazing autobiography. We’re all the better for it.

Born in 1880 into the shabby-genteel world of a lower-middle-class, Dublin Protestant family, O'Casey was six years old when his father died, leaving a family of 13 to fend for itself.

As O’Casey would later somewhat drily recall, “All the world’s a stage, and most of us are woefully unrehearsed.”

Because of an eye disease, O'Casey’s schooldays were few. However, he taught himself to read and in his early teens mastered Shakespeare.

His lifelong passions were theatre, music, and politics; he mixed them with abandon.

Long on principles, short on patience, Sean O’Casey did not suffer fools easily and never forgot a slight.

If his life was etched in poverty, O’Casey refused to be humbled by it. Indeed, he was fired from his position as a lowly clerk in Eason’s newspaper business for refusing to doff his cap when receiving his wages.

Sean O’Casey doffed his cap to no man and was consequently often unemployed.

He was even less successful in affairs of the heart, for his lack of income and Protestantism severely limited his marriage prospects in the largely Catholic world he inhabited.

Nonetheless, he threw himself into the churning political and cultural life of early 20th Century Dublin, and crossed paths – and often swords – with many of the prominent men and women of his day.

Along with Pádraig Pearse and other nationalists, he founded the famed St. Lawrence O’Toole Pipe Band and took up that most difficult of instruments, the Uilleann pipes. In a fury over his constant rehearsing, O'Casey’s brother eventually took an awl to his wailing pipes.

Outraged by the living conditions in Dublin slums, O’Casey became an avid trade unionist and socialist revolutionary. He came under the influence of Jim Larkin’s towering personality and was one of the founders of the Irish Citizen Army. However, he cared little for his comrade, James Connolly, and they clashed over the Scottish socialist’s perceived tilt towards Irish nationalism.

After disagreeing with Countess Markievicz on similar issues, he resigned as Secretary of the Citizen Army.

This would ultimately save his life, for it’s hard to imagine that the British authorities would have shown clemency towards the fiery proletarian revolutionary after the 1916 uprising.

With time on his hands, O’Casey began to write for the theatre, and after many rejections, he scored three massive successes with "Shadow of a Gunman," "Juno and the Paycock," and "The Plough and the Stars." Each a perfect blend of tragedy and comedy, these searing plays laid bare the effects of poverty and religious and patriotic cant on the Irish soul.

But O’Casey was never totally accepted in any field – riots broke out in the Abbey Theatre during "The Plough and The Stars" over his portrait of a prostitute in “holy Catholic Ireland.”

After The Abbey rejected his anti-war drama "The Silver Tassie," O'Casey moved to England. Though he is recognized as one of the world’s greatest playwrights, he never repeated the success of his dramatic Dublin trilogy.

And so he turned to memoir, and in six volumes with the umbrella title, "Mirror in My House," we get a detailed insight into eighty years of Irish political, social, and theatrical history from an acid-tongued observer.

Sure he settled a score here and there, and if he was harsh on James Connolly at least we get to see the man rather than the legend.

And oh the heartbreak! Was there ever a more searing rejection than his beloved ignoring the impoverished workman when out walking with her well-heeled friends?

Sean O’Casey not only changed the world of theatre, but he also took the time to put the passion and pain of his eventful life into print for the rest of us to marvel at.

He may have been peevish, harshly ideological, and easily wounded, but the Dublin playwright/navvy summed himself up best: “I’ll go the last few steps of the way rejoicing; I’ll go game, and I’ll die dancing.”

* Originally published in January 2018, last updated in September 2024.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments