Ireland's folk music is renowned the world over for its melodic beauty and rhythmic vibrance. Less well known is the fact that some of the most important exponents of this music have been blind.

Hundreds of years since blind musicians first plucked Irish harps, blind and vision-impaired musicians are drawing on this ancient tradition to perform as equals with sighted musicians in a uniquely Irish orchestra. Composer and orchestra director Dr. Dave Flynn tells the story of how Ireland's tradition of blind musicians led to a new vision for orchestral music.

Dr. Dave Flynn (Photo by John Kelly)

In the 17th Century, employment opportunities for blind people were far more limited than they are even today. In Ireland, a novel solution was developed which was enabled by the very nature of Irish folk music. Music was considered one of the few viable professions for a blind Irish person. This was possible because Ireland's is primarily an oral music tradition. Irish folk music is passed down, not by sheet music, but by practical one-to-one oral learning. Eventually, sheet music became a tool for preserving the bare skeleton form of Irish folk music, yet still, the majority of those who learn the music do so by ear. Indeed, that is the only way to fully grasp the hidden complexity of a music that cannot be truly expressed in notation, like Western classical music is.

O'Carolan and the blind bards of Ireland

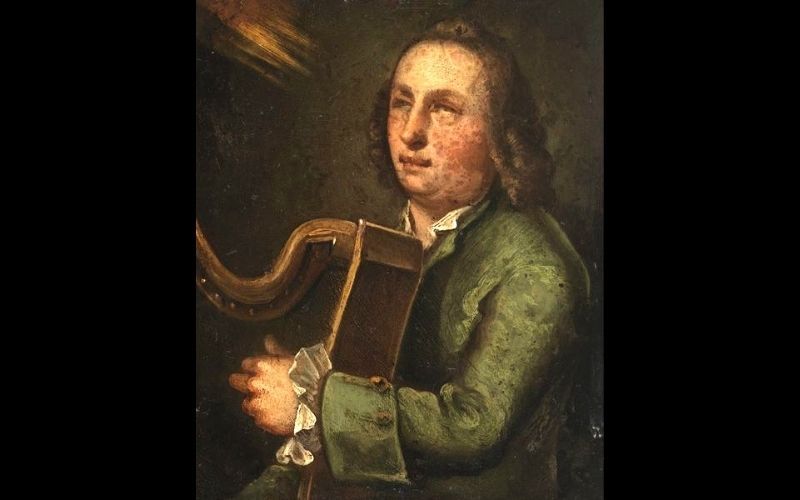

Portrait of Turlough Carolan, from R.B. Armstrong "The Irish and Highland Harps", Edinburgh, David Douglas, 1904. (Public Domain)

It is this fundamental difference between Irish folk music and western classical music which enabled generations of virtuoso blind musicians to develop in Ireland. Of these, the harpist Turlough O'Carolan (1670-1738) became renowned as Ireland's greatest composer of the Baroque era. He never needed to notate his music, so what notation exists of his compositions likely does not reflect the full scope of his musical vision. Notations of O'Carolan's music usually consist of single-line melodies transcribed by collectors, sometimes embellished by arrangers to include harmony. To sense how O'Carolan may have played his own music, listen to modern harpists like Anne-Marie O'Farrell, Paul Dooley, or Laoise Kelly, each of whom brings their own perspective to O'Carolan's music.

The haunting air 'Tabhair dom do Lámh' (Give me your hand), so popular at Irish weddings, is attributed to a blind harpist Ruaidhrí Dall Ó Catháin. One scholar, Keith Sanger, believes Ó Catháin never existed and was an invention of another blind harpist, Arthur O'Neill! Perhaps it was O'Neill then who composed the music attributed to Ó Catháin? Whatever the truth is, the fact remains, the ancient tradition of Irish harping was significantly developed by blind bards. Numerous other blind bardic harpists travelled Ireland for their living, playing and teaching music in exchange for bed, board, patronage, or, in less fortunate circumstances, spare change on the street.

Read More: Meet the Irish writer who rowed down the Nile and explored the world of the blind

The Blind Pipers of Clare

Within the Irish 'uilleann' piping tradition, there existed two particularly famous blind musicians, both from County Clare.

The fame of Pádraig O'Briain (c1773-1855) largely rests on a painting by Patrick J. Haverty called 'The Limerick Piper.' According to Clare County Library, this became one of the most popular lithographs in the 19th century. The painting however paints a false picture of O'Briain as a well-dressed gentleman piper. In reality, he struggled through life as a street musician, dying a pauper six months after he fatally fell on the Limerick ice.

Patrick O'Brien: The Limerick Piper by Joseph Patrick Haverty. (Public Domain)

O'Briain's legacy must not have gone unnoticed by Garrett Barry (1847-1899), one of Ireland's greatest ever pipers. Barry was trained on the uilleann pipes after he lost his sight aged-two as a result of Ireland's devastating Great Famine. Barry was more fortunate than O'Briain, becoming in great demand as a traveling musician and storyteller, entertaining people around Clare at dances and other gatherings. The rich tradition of Clare music celebrated annually at the Willie Clancy Summer School can be traced back to Garrett Barry, as Barry taught Willie Clancy's father Gilbert.

Read More: Master piper Liam O'Flynn's life's works examined in TG4 documentary

Vision-impaired Fiddlers

Vision-impaired fiddle players have also had an important impact on the Irish tradition. In Clare, for example, two blind fiddlers helped preserve what was becoming a dying tradition by the late 19th and early 20th Century. Paddy MacNamara and Schooner Breen travelled the county teaching music to people whose offspring would go on to great things. MacNamara taught Pat Canny, father of All-Ireland fiddle champion Paddy Canny, himself the uncle of one of the most renowned fiddlers today, Martin Hayes. One of Breen's students was the mother of concertina legend Elizabeth Crotty.

Many more blind musicians of note are detailed in the 1913 book Irish Minstrels and Musicians, by famed Chicago police chief and music collector Captain Francis O'Neill. This book confirms the extraordinary legacy of blind and vision-impaired musicians in Ireland.

Read More: WATCH: Irish youth orchestra's touching rendition of With or Without You

A Symphony for the Blind

This is a legacy I celebrated with my 2019 orchestral work The Vision Symphony. It is a four-movement work, with each movement dedicated to the memory of the blind Clare musicians mentioned above. More importantly, it is a tribute to blind and vision-impaired musicians living today, as it was composed in a way that would open access to orchestral playing to those previously excluded, because they could not sight-read sheet music.

In 2012, I formed the Irish Memory Orchestra with the aim to create a uniquely Irish orchestra that would draw equally on Ireland's oral folk music tradition and the notated western classical tradition. Though I notate the music I compose for the orchestra, the musicians always play it by memory in concert. Some of the musicians are not classically trained and as a result they either cannot read music or have limited sight-reading skills. Therefore, I create audio learning files so they can learn the music by ear. I also give the musicians freedom to subtly improvise, within the traditions of Irish folk music, jazz and popular music.

This new approach to orchestral music has a serendipitous by-product, it enables blind and vision-impaired musicians to perform with my orchestra. In 2013, the orchestra developed an outreach scheme where we invited talented apprentice musicians from around Ireland to join the professional 20-piece Irish Memory Orchestra to perform, by memory, my hour-long piece The Clare Concerto. One applicant was a young blind violinist, whose mother told me she had been excluded from other orchestra training programs because they could not cater to her vision-impairment. We accepted her to our scheme however, sadly, college commitments meant she had to forgo her place.

Two years later a vision-impaired harpist called Emily Kelly successfully applied to the scheme, passing the audition without mentioning her impairment. So adept is she at living with her impairment that I did not know she was visually impaired until three years later, when we put a call-out for a new project – The Vision Symphony.

Thinking about the example of the young violinist who had been excluded from other orchestras, I wondered whether it might be possible to create a symphony tailored to enable several blind and vision-impaired musicians to perform with orchestras. Following a two-year research and development phase, supported by Ireland's Arts Council, Clare Arts Office, 3L Music and others, my Vision Symphony was premiered in October 2019 by a 45-piece Irish Memory Orchestra, which included 26 blind and vision-impaired musicians and singers.

This excerpt from the Journal of Music’s review sums up the significance of that event:

Flynn’s craft in combining traditional and contemporary music elements is always something to appreciate, but here he achieved more: he has broken down boundaries for people with sight loss; with an orchestra that plays by memory and with vigour under conductor Bjorn Bantock; and he has again shown what is possible when you use elements of Irish traditional music in a fresh way. Were we surprised? How could we not be? In a world of musical adventure, this was boundary breaking in a new way.

The story of the production of the Vision Symphony is told in a short Myles O’Reilly documentary available on the Irish Memory Orchestra's YouTube channel.

A new adaptation of the Vision Symphony, for a larger orchestra and choir, is due to premiere in Galway in 2021. Hopefully by then, Covid-19 restrictions will be a thing of the past and we can continue our work to enable blind and vision-impaired musicians to perform in orchestras, as equals with their sighted colleagues.

For more info about the project and how to be part of our new musical vision, please visit the Irish Memory Orchestra’s website.

*Dr. Dave Flynn is a composer, guitarist, writer, educator and orchestra director. He holds a Ph.D. from TU Dublin. His award-winning work has been acclaimed in the Irish Voice (sister publication to IrishCentral), New York Times, Irish Times, The Times (UK) and WNYC, among others.

Comments