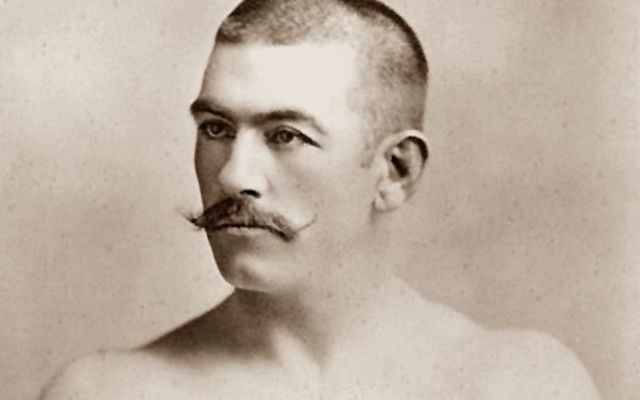

Born to an impoverished Irish family that fled the Great Hunger, he managed within one generation to change their fortunes and embody the American dream. He did it all with his bare hands. Cahir O'Doherty talks to author Christopher Klein, who wrote the rollicking and remarkable biography of John L. Sullivan.

John L. Sullivan, the first modern heavyweight boxing champion of the world, was the father of them all. The most successful athlete of his era, he was also the first to earn more than a million dollars for his efforts, an extraordinary achievement in the 19th century.

But Sullivan was also a big boozer, a braggart, and an insatiable womanizer. He could be a hell of a lot of fun, in other words. Through his long career, he became a sort of a cross between Muhammad Ali, Casanova, Mark Twain, and Amanda Bynes. Tabloid editors loved him. He wasn’t just a sportsman; he was a star in the modern sense.

Men who fought him say his right hook felt like being hit full force by a telegraph pole.

“I can lick any son-of-a-bitch in the world,” Sullivan used to say, with justification. He was gifted and he had his demons, but he bested every challenge that came his way.

In "Strong Boy, The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan", the book that should go straight to the top of your wish list, Irish American author Christopher Klein has written an immensely entertaining and insightful biography that’s worthy of his formidable subject.

“Boxing has a pretty rich tradition in Boston that stretches back to John L. Sullivan and to when the Irish started arriving here in record numbers during the Famine in the 1840s.

“Then Klein began to realize what an impact Sullivan had had on the world we live in now. He was the first sports superstar, he appeared right at the birth of modern celebrity culture, and he was a trailblazer for modern sports with all their crazy fans and corporate endorsements. Because of that the sepia tones of the gilded age turn into bright color,” says Klein. “I thought it was time to freshen up his story a little bit.”

Like so many Irish tales, it starts with the famine, that ghastly Year One of Irish history. In 1845 Boston was a city of little more than one hundred thousand. But thirty-seven thousand Irish people arrived in the year 1847 alone. By 1850 the Irish represented over one-quarter of Boston’s population.

Sullivan’s father Michael was among their number. Originally from Laccabeg in County Kerry, the only thing that guided him in his new life in the new world was the certainty that it had to be better than the hell on earth he had sprung from.

So the trauma of the Great Hunger, the sheer unspeakable scale of the calamity, was the formative experience of Sullivan’s father’s generation and that collapse and failure haunted their dreams, their lives and damaged their sense of themselves and their aspirations.

They needed a hero and boy did they get one. “I’m not a boxing fan per se,” Klein explains. “What drew me in was Sullivan in his cultural standpoint. Here you have both his parents leaving Ireland in the wake of the Great Hunger. They’re very representative of that first generation coming here. They were just so beaten down, so defeated. Then in Boston, they find the Protestant Brahmins are ruling the city and they have the Irish under their thumb.”

Suffering from what Klein calls the deleterious effects of malignant shame, Sullivan’s parents were astonished by the literally fighting spirit of their son’s generation.

“He becomes the most powerful man in the world, no one can beat him, and he has Irish blood running through his veins. He’s the literal embodiment of the spirit of the fighting Irish. He’s an elixir for a generation of his own downtrodden countrymen,” says Klein, in a pitch that seems perfect for the Hollywood biopic of Sullivan’s life.

There’s good reason to think it would play well. Sullivan’s story is the story of the Irish coming of age in America, really. It bridges worlds, the old one and the new one. When Sullivan was at the height of his powers and fame the first Irish mayor was elected in Boston, and the Irish really started getting involved in the political scene. It wasn’t a coincidence. He helped inspire them. The parallels and overlap are self-evident.

“Sullivan was friends with James Michael Curley, the first Irish mayor of Boston,” says Klein. “But he was born in a tenement, his father was a mason, he worked in many manual labor jobs, he was from a hardscrabble background. It was a very typical upbringing for a lot of the Irish in Boston so they felt a strong natural connection to him."

Sullivan had made his mark in Boston before he became a national figure. There had been previous champions, but it was Sullivan’s sheer force of personality that meant people were able to connect to him in a new way. He was a guy who literally worked with his hands to make a living, people could relate.

“Sullivan did something that was unique. After he won the world title in 1883 he set out on a barnstorming tour of the United States. He literally challenged all of America to fight him. He said he would pay $250 dollars to anyone who would stay in the ring with him for four rounds (there were few takers).”

Sullivan’s whistle-stop, 200-date national tour, was the first of its kind and it allowed tens of thousands to see him in the flesh. From Irish heavy strongholds like Chicago to the mining town of Colorado to the gold rush towns of California, he encountered the Irish in the mines, in the boomtowns and building the railroads, creating the infrastructure of the United States and laying the foundation of the modern America.

“Seeing famous people in the flesh is how you build celebrity. John L. Sullivan and Buffalo Bill were the two people in America who had the most eyes on them. In an era where the president would hardly travel out of Washington this made a stark contrast.”

The tour made him famous and it began to make him rich. In Klein’s mind, he’s the first American sports superstar. Remember, this tour is forty years before Babe Ruth. Along the way, he set the gold standard for his sport and became its champion for a decade in an era where people associated boxing with low-class settings if they thought of it at all. Sullivan’s career changed that perception.

“He arrived at the start of the tabloid broadsheet when the railroads and the mass media were really getting started,” says Klein. “Papers like The New York World and The National Police Gazette could make hay with his drunken binges, his arrests and his boasting. At one point he knocked down a horse and got arrested for that. He was a dream for news editors and so he dominated sports pages and front pages. He’s got these wild weight fluctuations, he’s got a drinking problem, and he’s a womanizer. People couldn’t read enough about him.

At the time Sullivan began his career, bare-knuckle boxing, like prostitution and gambling, were illegal in New York but practiced everywhere. Promoters still found ways to host prizefights. Cops were paid to look the other way; crackdowns were followed by new opportunities.

But Sullivan insisted early on fighting by the Queensbury rules, which in fact continue to this day. He was the last of the bare-knuckle fighters and the first of the modern champions that we know of these days, says Klein. His first fights were held in barrooms and his final fight was held in a 10,000-seat arena lit by electric light and he wore gloves. In between, he became rich and famous.

In a lovely coda to a richly lived life, Sullivan made the trip back to Ireland in his old age, a moneyed and famous man, to see the place in County Kerry that his father had fled from

“There’s a real redemption at the end,” says Klein. “In his final years, he bought a farm with his second wife in a town about 20 miles south of Boston. They lived there very happily and called it Donnellyross Farm, an amalgamation of Donegal, Tralee and County Roscommon.”

The most successful crop on Sullivan’s farm was – you guessed it, potatoes.

*Originally published in Nov 2013, updated in Sept 2022.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments