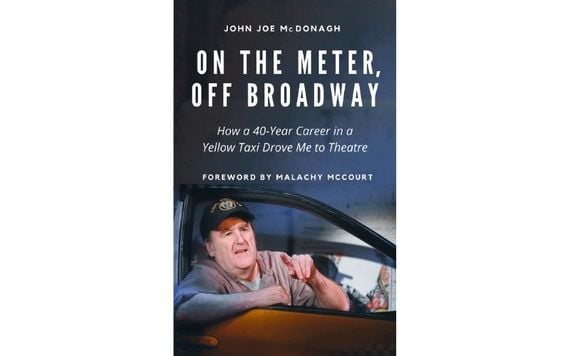

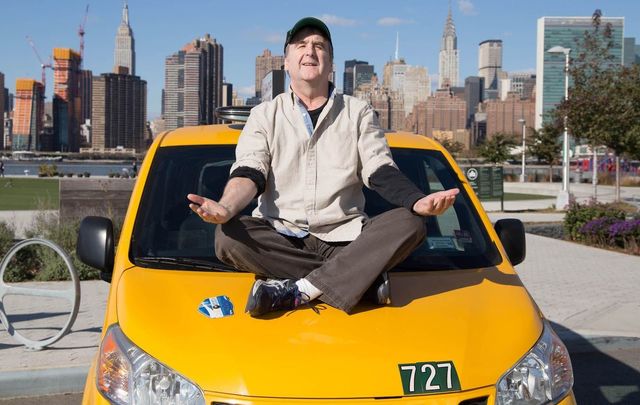

John McDonagh, who drove a New York City yellow taxi for 40 years, has turned his play Off the Meter, On the Record into a book called On the Meter, Off-Broadway, which will be published later this year.

Under the direction of Ciaran O’Reilly, Off the Meter, On the Record wowed audiences during a three-month run at the Irish Repertory Theatre in Manhattan. John McDonagh is bringing it to the Sean O’Casey Theatre in Dublin and the Abbey Arts Centre in Co. Donegal later this year.

The following is an excerpt from the book:

I can't think of a better place to watch the world go by than behind the wheel of a New York City yellow taxi. Although I grew up with one foot in Middle Village, Queens and the other on a sheep farm in rural Donegal, I am a city kid at heart. I love the fast pace and constant motion of the city, that it truly never sleeps, and those rare moments when the grit, crime and smog fade into the background, and you can almost feel the sense of possibility in the air.

Read more

I didn’t wake up one day and say, “You know what my dream job would be? Cab driver.” Twists and turns of life and a few quirks of fate led me to getting a hack license.

My road to becoming a playwright, actor, and author was equally improbable. Never in a million years did I think as I dragged myself into the garage at three in the morning that I would one day be on the stage at the Irish Repertory Theatre. The only thing I did know was that I had a lot of stories, and a bit of the genetic trait that courses through Irish DNA, a way with words.

****

DURING my 40 years of driving, I have watched a once-proud profession that would allow you to make enough money to raise a family to descend into a race for the bottom. Now drivers can barely make enough to pay the lease fee at the end of a 12-hour shift.

When I started driving a yellow cab after being honorably discharged from the army in the seventies, I joined the taxi union. The take for the night was split between the driver and the garage, 55 percent to the garage, 45 percent to the driver, and the garage paid for the gas.

McDonagh’s U.S. Army portrait.

If the driver had a good night, the garage had a good night. If you had a bad night, the garage had a bad night. At that time, all fares were paid in cash. A driver could make more money by asking the customer to pay “off the meter,” which was generally less money, and would give more money to the driver at the end of the night.

Before there were computers or GPS, Stanley, owner of the garage I worked out of, created an algorithm in his head that would immediately detect if a returning driver had been working off the meter. Weighing up what the other drivers were returning with and the mileage on the car, he could almost smell the scent of an off-the-meter fare. He would confront the driver, screaming, “You screwed me tonight” and would put that driver on punishment, telling the driver to take the next night off, and giving that driver the worst car in the lot, likely to break down during the shift.

As harsh as that sounds, I have come to look back at those times as the glory days. As time went on the taxi union dissolved and the garage owners grew tired of sharing the risk with the drivers.

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

Instead of splitting the night’s take with the garage, drivers are now charged a flat lease fee for 12-hour use of the cab. If fares were far and few between, the cab got a flat, or worse, had an accident, it was irrelevant to the garage owner. The driver still had to pay the entire amount of the lease and return the cab with a full tank of gas. As gas prices rise, drivers’ takes go down but the owner is unaffected.

The pressure to make enough money to pay for the lease and make any profit took a hard toll on drivers. Kidney disease, diabetes, and heart disease were all avoidable consequences of sitting for 12 straight hours with few opportunities to use a bathroom or have something healthy to eat.

****

AFTER 40 years of driving through the pollution of New York City, I suspect I could qualify for a lung transplant. Twice I saw my life pass before my eyes -- once when I had a gun put to my head; another when I had a pick put against the side of my neck while the money was taken from my shirt pocket. A stark reminder never to let a passenger sit in the front seat.

Having told many of these stories -- mainly at Rocky Sullivan’s Pub over a pint of Guinness -- driving became something I got far more enjoyment from talking about than actually doing. I started writing down the stories and thinking of how to structure them in a way that made sense.

I’d walk around the house, practicing different versions for the dog. I brought it, piece by piece, to the Irish American Writers and Artists salons, and got invaluable feedback and encouragement.

Then an email from Larry Kirwan set me solidly on the road from barstool to the boards, and two years later I ended up in a place I never in my wildest dreams thought I’d be -- the Irish Repertory Theatre. What follows is the script. I went from driving off the meter to performing Off the Meter, On the Record.

****

BEFORE there was Waze, before there was Google Maps, there was New York radio station called 1010 WINS. For a New York City yellow taxi driver, tuning in to 1010 WINS was as much a part of the daily routine as filling the tank with gas.

The traffic report, broadcast once every 10 minutes, was a lifeline for cab drivers. It made it possible to avoid unexpected street closures due to manhole cover explosions, water main breaks and good old-fashioned traffic jams.

Read more

In earlier years a passenger would simply bark out an address, trusting that the driver would know the fastest route. Now when a passenger gets into the cab, before the address is even given is the instruction, “Google says take the FDR.”

1010 WINS and a driver’s decades of experience can no longer compete with the passenger’s electronically sanctioned route. But for many years, the soundtrack of my life was 1010 WINS. You give me 22 minutes, and I’ll give you the world.

The road to getting my hack license began when I graduated from Grover Cleveland High School in Ridgewood, Queens in 1973. When I got out of high school there weren’t many opportunities so myself and four of my friends went down to Myrtle Avenue and signed up for the United States Army.

Now mind you, the draft was ending that year and the Vietnam War would go on for another year and a half.

Another reason that 18-year-olds should not be able to make adult decisions. From there we went down to Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, where we were sworn in, and then flown down for basic training to Fort Jackson, South Carolina.

I was a hippie with long hair when I got down there and first stood at attention. A drill sergeant came up to me and said, “Where y’all from, boy?” I said, “New York City.”

He said, “Welcome to the United States of America. I’m glad you made.”

Thus began my two-year nightmare in the United States Army.

After basic training in South Carolina, I was shipped overseas to Germany to a town called Wurzburg. When I got to Germany, the base was overrun with heroin that was coming in from Turkey and hashish from Holland.

And almost on a monthly basis, there were race riots between the white and black soldiers on the base. Soldiers were stabbing each other and getting beat up with baseball bats. We were reflecting on what was going on in America. It was a very dangerous time to be in the United States Army.

After my time in Germany, I came back to New York City and like a lot of things in life, timing is everything. The headline that greeted me in the Daily News was: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD”

As a son of Irish immigrants, my career path was supposed to be: You graduate high school. You do your time in the service, come back. You take the Sanitation, NYPD, and Fire Department tests.

But at this stage, they were laying off cops and firemen. College? We didn’t even talk about this at home. My mother and father left school in Donegal in the sixth grade to work on the farm. The goal was to get a good union job. But that wasn’t an option either. So what does a child of immigrants do next?

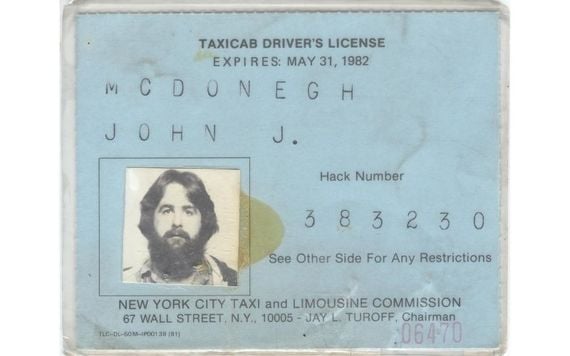

I went and got my hack license.

McDonagh’s hack license.

Now when you get your hack license from the Taxi and Limousine Commission, generally most drivers hold them for an average of five years. Because when you get your hack license, it’s a stepping stone to something else. You're getting another job. You’re going to have another occupation. You’re going to go to college.

You never think you’re going to drive for more than five years because surely to God the economy is going to turn around and you’re going to get a better job.

Well, the years turned into decades. I have now been driving in two centuries.

Do any of you ever wonder what it’s like to be a cab driver? As a matter of fact, you’re off to a very good start right now. You are sitting down. Stay sitting down where you are now for the next 12 hours. Piss into a bottle. Have a person sit down behind you and vomit. Now you know a little of what it is like to be a Yellow cab driver.

Now drivers want to know: what does society think about cab drivers? One of the best barometers is The New York Times, the paper of record.

There was a famous jazz musician named Duke Jordan. When he died, this was his obituary in the Times: “Like a lot of his contemporaries in the sixties, he became addicted to heroin. He was then reduced to driving a cab in New York City,”

So as you can see, the only way I can go up now in life is to become a heroin addict. So much for what The New York Times thinks of us.

****

NOW there are a lot of problems here in New York City. We’ve got homelessness, we got the gangs, we’ve got shootings. But when Mayor Bill de Blasio was elected he was fixated on only one thing: he had to help the horses in Central Park.

Now the horses in Central Park are way better off and have more benefits than yellow cab drivers.

As far as a need to protect them -- when is the last time you heard of a horse being shot in the head in Central Park? Or someone jumping out of the carriage and running into the Plaza Hotel to avoid paying the fare?

It doesn’t happen. But it happens to us, quite often.

No, the horses in Central Park are unionized. They are teamsters, unlike yellow cab drivers, who are independent contractors.

Here are the benefits that Central Park horses have:

They are showered and scrubbed twice a day.

If you’ve ever taken a ride in a yellow cab, you know that’s optional for the driver.

The horses in Central Park have a medical plan where they see a doctor twice a year.

A yellow cab driver sees a doctor when he first goes for his hack license, and the next time a doctor sees him is when there is a nine-millimeter hole in the back of the head, and he’s pronouncing you dead.

The horses in Central Park only work eight-hour days.

The yellow cab driver working out of a garage might work 12 hours a day.

There was recently a hearing at the Taxi and Limousine Commission where the commission wanted to limit the taxi drivers’ hours to 12 hours per day. The people protesting this were the cab drivers, who were saying that we had to work 15-16 hours a day to make a living.

This is the America we are living in. We are now fighting for the 16-hour day.

The horses in Central Park don’t work in temperatures about 90 or below 17, whereas in yellow cab drives, we work during Hurricane Sandy, 9/11 -- it doesn’t matter what the temperature is, or the weather conditions. We’re always working.

The horses in Central Park have a two-month vacation where they are sent out to Pennsylvania to graze on grass.

Yellow cab drivers? We have no vacation. Not only can we not graze on grass, we can’t even smoke it because we have a urine test as a cab driver once a year. The horses in Central Park are union horses and have privacy rules so they are not drug tested.

The horses in Central Park retire after 10 years and they are sent off to a stud farm in Long Island.

I’ve already told you how yellow cab drivers are retired -- a shot to the head or heart attack behind the wheel. But I’ll leave it to you to imagine the horrors of a yellow cab driver stud farm.

Another way that you know what your status in life is -- particularly here in New York -- is where you live.

All the horses in Central Park bar none live on the West side of Manhattan. Yellow cab drivers? We live in basements in Brooklyn and Queens.

So if you believe in reincarnation, come back as a horse in Central Park.

(For more, visit www.offthemeter.net)

Celebrate everything Irish this March with IrishCentral's global community.

Comments