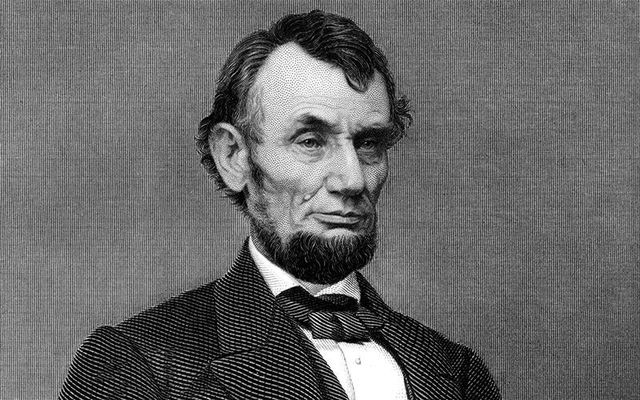

"Lincoln and the Irish" by Niall O'Dowd reveals the story of Abraham Lincoln and the Irish during the Civil War.

“If you are a fan of Lincoln like me you will love this book.” - Liam Neeson

"An impressive work of scholarship." - Terry George, Oscar-winning Director of "Hotel Rwanda"

"Tells superbly how Abraham Lincoln changed from suspicion of the Irish to deep respect." - Tim Pat Coogan, Ireland's leading historian.

For the first time, the full story of Abraham Lincoln and the Irish is told in Niall O’Dowd’s book “Lincoln and the Irish: The Untold Story," published by Skyhorse Publishing which has had 46 books on the New York Times bestseller list.

There are 15,000 books on Lincoln; this is the first one on Lincoln and the Irish.

Read the first chapter of "Lincoln and the Irish" by Niall O'Dowd below.

Lincoln knew the Irish, more than any president other than JFK. He loved their songs like Kathleen Mavourneen and read Emmet’s speech from the dock. He gave to famine relief and eagerly signed onto a House bill condemning the treatment of the Young Irelanders.

His children were raised by Irish nannies, despite the fact that his wife Mary Todd Lincoln disliked the Irish and threatened to support the nativist Know-Nothings against them.

Lincoln fought with them as political rivals in Springfield, ending up seconds away from a duel with a remarkable Irishman called James Shields from Tyrone, the only man in history to be selected from three different states as a US senator.

Lincoln called the near duel the lowest moment of his life.

When Lincoln got to the White House he was greeted by the ageless Ed McManus the Irish doorman and a predominantly Irish staff.

He spent so much time with them other jealous staffers referred to them as his “Hibernian cabal.” McManus was said to be the only man who could make the president laugh. Lincoln was even known to affect an Irish accent at times.

The Irish formed the backbone of the Union Army, so much so that Jefferson Davis dispatched a bishop and a famous Irish priest to Ireland to plead with the Catholic Church there to stop Irish emigrants joining Lincoln’s army.

On the battlefield 150,000 Irish fought for Lincoln and democracy in the Civil War, yet historical series like the Ken Burns one hardly mentioned them.

The Irish were awarded 146 Medals of Honor and Lincoln himself kissed the Irish flag and said, “God Bless the Irish" after Malvern Hill. The Pennsylvania Irish 69th played an incredible role at Gettysburg where they stood alone for a time against Pickett's charge -- an almost forgotten key moment.

The New York Fighting 69th fought heroically on many civil war battlefields, nowhere more gallantly than Gettysburg.

Incredibly, On the battlefield, one of Lincoln's bravest fighters was a transgendered soldier from Ireland, a truly incredible story. She was the only female soldier who continued life as a man after the war was over.

Soon after arriving from Ireland Jenny Hodgers became Albert Cashier and stayed Albert Cashier all his life.

At the height of Lincoln’s political career, 19,000 Irish a month were flooding through American ports, fleeing the aftermath of famine and starvation. They received a cold welcome.

The Know-Nothings, the Klansmen of the day, targeted them, culminating in burning up to a dozen Irish alive on August 6, 1865 “Bloody Monday” in Louisville, Kentucky when they tried to vote.

Crowd of citizens and soldiers with Abraham Lincoln, during the Gettysburg Address.

Read More: Irish letter by Abraham Lincoln up for auction on St. Patrick's Day

Two Irishmen were with Lincoln as he arrived at Ford's Theater on that fateful night, their role now lost to history but revived here. An Irishman was the last person to talk to the assassin Booth. The man who tracked Booth down was an active Fenian and an Irish hero. In a remote Sligo graveyard, there is a mysterious monument to him that simply reads "Lincoln's Avenger."

There's just so much more to read about, but here is the book’s first chapter:

Abraham Lincoln and the Irish: The Untold Story

By Niall O’Dowd

CHAPTER ONE

SCOOP OF THE CENTURY

In the misty early morning of Wednesday, April 26, 1865, three men in a small rowing boat set out from Crookhaven, a tiny fishing village in County Cork, Ireland, to intercept the mail steamer Marseilles.

The Marseilles had rendezvoused off the Cork coast and picked up canisters of US mail from the Teutonia, a Hamburg-bound ship via Southampton which had left New York twelve days earlier. The Teutonia had loomed into view off the Irish coast at 8 a.m. It was carrying the latest news from America.

The three men, the lookout who had first sighted the ship from a rocky outcrop called Brow Head, and the men on the mail ship itself, were all paid employees of Paul Julius Reuter, a dynamic newspaperman and German immigrant who was determined to have the news first, whatever it took. His name would become a household one soon enough because of the events of that day.

Like all successful men and women of business, Reuter saw an opportunity and took it. In his case, it was building a private telegraph line from Cork City to Crookhaven, the first point of land close enough for a ship from America to be intercepted. The other news services would wait until the ship pulled into Cobh, then called Queenstown, some twenty-five miles further up the coast. Time was money, and Reuter was in a hurry.

At the time, it took about twelve days by steamship to cross the Atlantic. Telegraph lines west from London stopped at County Cork. In America, no working lines yet crossed the Atlantic though there had been many attempts.

Thus, in April 1865 any news from the United States would first come from the mail boat picking up from the transatlantic steamer in the waters off County Cork, the closest landfall, and would then be quickly routed to London and Europe through the Cork City cable office.

If Abraham Lincoln had died just one year later the news would have reached Europe almost immediately, as the first working transatlantic telegraph cable would make land at Valentia Island off Kerry. In 1866. It could handle eight words per minute.

The Marseilles this day would carry the biggest story of the century—the assassination of American president Abraham Lincoln. Though he had been shot on April 14 and America was ablaze with the news and the successful hunt for the assassin, Europe remained blissfully unaware until twelve days later.

The main news in the London Evening Standard was the celebration and events around the tercentenary of the birth of William Shakespeare and the death of the elder brother of the Czar of Russia.

That was about to change.

The key man was James “Tugboat” McLean Reuter’s man in New York.

McLean was Reuter’s go-getting correspondent, in those days called an agent. He was later called “Tugboat” because his news of Lincoln’s death almost came too late to put aboard the Teutonia. He pursued the ship on a tugboat and threw the watertight canisters containing his historic report aboard.

Some claim it was a different man than McLean, a fellow German James Hecksher, a friend and New York employee of Reuter’s, who pursued the tugboat and threw the canisters on board.

Onward the ship sailed across the wide ocean, bearing its message of profound importance and impact, before transferring the news canisters to the Marseilles. When that ship came in sight of Irish shores, the purser lowered the canisters and dropped them in the water as the ship drew close to the three men who had rowed out. They snagged them with nets on long poles like huge fishing nets.

They rowed back to Crookhaven, where the telegraph operator broke open the canisters and read their sensational import. Soon, the telegraph lines between remote Cork and the great cities of Europe began a chatter that soon built to a frenzy. By the noon bulletin, hours before his rivals, Reuter broke the news that shocked the world. It was so shocking that many thought it a hoax, and Reuter’s reputation was on the line. A few hours later, it was confirmed.

The Great Emancipator Abraham Lincoln was dead.

Reuter’s news hit Britain and Ireland like a thunderbolt.

“The blow is sudden, horrible, irretrievable,” wrote the London Evening Standard. “Never, since the death of Henry IV [of France] by the hand of Ravaillac—never, perhaps, since the assassination of Caesar—has a murder been committed more momentous in its bearing upon the times.”

England wept, Ireland too. Lincoln had been a hero to so many. Grown men cried openly. American consulates were besieged. Church groups, anti-slavery societies, labor groups, chambers of commerce were devastated. Historian Richard Carwardine described that there were some Confederate supporters gloating on the floor of the Liverpool Stock Exchange. One trader cheered, but was thrown out by another who said, “You incarnate fiend, you have the heart of an assassin yourself!”

A “cult of Lincoln,” in the words of George Bernard Shaw, sprung up in Britain after his death and arguably has continued ever since. In 1920, a statue of Lincoln sculpted by Irish-born sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens was unveiled in Parliament Square, entitled “Lincoln the Man.” Prime Minister David Lloyd George was present. Civil War veterans attended.

The cult spread to Russia, where forty-five years later Leo Tolstoy stated, “The greatness of Napoleon, Caesar, or Washington is only moonlight by the sun of Lincoln.” He predicted that “his example is universal and will last thousands of years.”

Reuter was forever famous for bearing the news. Hollywood even came out with the film A Dispatch from Reuter’s in 1940, starring Edward G. Robinson as Reuter, about the events around getting the Lincoln story first.

The news of Abe Lincoln’s death first came ashore in Ireland. It would be the last connection between a legendary president and a country whose people had played a huge role in his life. Lincoln’s relationship with the Irish was an extraordinary story, too.

When the Kentucky backwoods rail-splitter set out on his extraordinary political journey, he encountered the Irish at every step. His rise coincided with the greatest ever inward migration of a people, the million Irish fleeing the Famine. In a country of just twenty-three million, the arrival of the Irish had an immense impact.

He knew them, fought them, embraced them, cursed them, thanked them profusely, and kissed their flag. He gathered a Hibernian cabal around him in the White House and was criticized for so doing. It is highly unlikely he could have won the most important war ever fought for the future of democracy without them. They were 150,000 strong in his army, which peaked at 600,000 men in late 1863. Irishmen had never fought in such numbers for their own country. The fuse was lit by the Civil War and in the tide of battle they were led by their heroes like Thomas Francis Meagher and Michael Corcoran.

Lincoln appeared to regard the Irish with a benign demeanor most of the time. Even in his most private writings, he exhibited none of the hatred towards them that many of his contemporaries, including his wife and law partner, did. He told Irish jokes, very mild in nature. The old Irish doorman Edward McManus at the White House was said to be the only person who could make him laugh with his funny Irish stories.

His children were cared for by them. He wined and dined their heroes, such as Thomas Francis Meagher and Michael Corcoran, and showed up at a Fighting 69th camp and kissed the Irish flag. Francis Burke, the man who drove him to Ford’s Theatre that dreadful night, was Irish, as was his valet Charlie Forbes, the last man to speak to the assassin Booth before he killed the president.

James O’Beirne and Edward Doherty, two men who were among the leaders who tracked down his killer, were Irish as well. General Philip Sheridan, who ended the war a folk hero on the Union side had family direct from Cavan and was either born there himself or more likely at sea on the voyage over.

When it came to the Irish, Abraham Lincoln was no stranger.

* Originally published in March 2018.

Comments