The title of the book, Kathleen, was spelled out in blue letters along the spine.

I was fourteen years old and in Waldenbooks at the Kings Plaza Mall, just blocks away from the Flatlands branch of the Brooklyn Public Library from which I was a fugitive, hounded by late notices, fines climbing dime over dime. The books were never lost. I just had trouble surrendering them.

There were several similar books in the same row as Kathleen. They were, I’d learn, Young Adult romance novels. Each story took a resourceful young woman and put her in the middle of a historical event where she met two handsome men and had to choose between them. Elizabeth is caught up in the Salem Witch Trials. Amanda travels the Oregon Trail. Caroline joins the California Gold Rush. Nicole survives the sinking of the Titanic.

Already a writer, my name anywhere on a book felt like a wink from the future. Before I even slipped Kathleen by Candice F. Ransom off the shelf, I knew I was going to buy it.

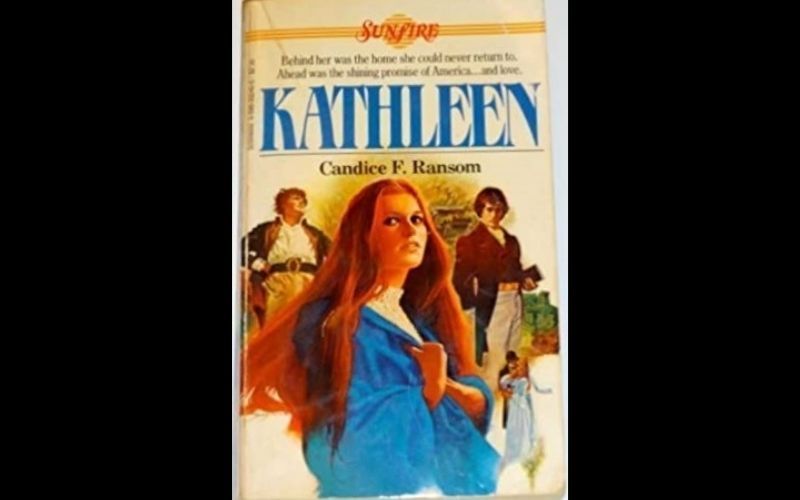

The cover featured a girl wrapped in a blue shawl with red hair flowing down her back.

Kathleen by Candice F. Ransom

It is 1847, and Kathleen O’Connor is fleeing a potatoes-only famine in Ireland. Her siblings have died of starvation and fever, as has the man she was going to marry. She sails for America with her parents, but by the time the ship arrives, Kathleen is the sole survivor of her family. In Boston, signs in store windows say, “No Irish Need Apply.” She becomes a pickpocket but, eventually, she gets a job as a maid to a wealthy family and begins to adjust to her new life.

This cannot have actually happened, I thought, stunned. In 1986, famine meant the terrible tragedy in Ethiopia. The same thing had happened in Ireland? And who hates the Irish?

My paternal grandparents were from Galway. I always said the names of their towns as though they were one, like the words of a magic spell. Tuam. Ballinasloe. My mother was of Irish descent as well. But I had not known.

Kathleen is neither graphic nor entirely realistic. Of course, as a book for young adults, it’s not meant to be. Kathleen’s brother and sisters are already dead when the book begins, and they were buried. A graveside funeral is mentioned. Kathleen not only speaks English, but reads and writes it, a fact that is met with great disbelief, as it would have been. Kathleen’s father is a poor farmer so to excuse her literacy, the author made Kathleen’s mother a Protestant. The two men Kathleen must choose between are an Irishman she met on the voyage over and the sensitive son of her wealthy (non-Catholic) employer.

I have been thinking about Kathleen a lot lately, given the publicity over the closure of Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum, which holds a singular collection of art and artifacts that tell the story of An Gorta Mór. The museum has been evicted from Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Connecticut, at the direction of its current President Judy Olian.

You can read more about it here in these two IrishCentral articles, one by Turlough McConnell from 2021 that explains what led to the closure, and one by Debbie McGoldrick with the most recent updates. Turlough McConnell has founded an organization called Save Ireland’s Great Hunger Museum. The goal is to keep the museum at Quinnipiac and its collection intact and open to the public.

Kathleen was my introduction to The Great Hunger. Since then, I’ve read many books about it, both nonfiction and fiction. The Great Hunger by Cecil Woodham-Smith. This Great Calamity: Ireland: The Irish Famine 1845-52 by Christine Kinealy. The Graves Are Walking: The Great Famine and the Saga of the Irish People by John Kelly.

I’ve also read many other novels that are about the years that you must comprehend, in order to understand anything about Irish history. In Leon Uris’s Trinity, the Great Hunger is the background for rebellion. Nuala O’Faolain’s My Dream of You moves back and forth between the end of the Great Hunger and modern Ireland, as her Kathleen attempts to reconcile them both. Peter Behrens’ Law of Dreams, features stunning scenes of workhouses and a gang of orphaned children living wild in the Irish countryside. Peter Quinn’s Banished Children of Eve brings the story to America, as does his nonfiction Looking for Jimmy, A Search for Irish America. Both explore the legacy of mass death and immigration, for the Irish and their American descendants. Ship Fever is a short story by Andrea Barrett about the influx of coffin ships at Grosse Île in Quebec and a medical staff overwhelmed by the tide of sick and dying Irish. My own novel, Ashes of Fiery Weather, is about a survivor of the Great Hunger who refuses to speak of it to her daughter, struggling to understand.

My copy of Kathleen disappeared, as things from childhood do. Years ago, I went online and bought one for about $25. I hold it sometimes though, a ghost turned substantive in my hands.

Epilogue / Prologue

My grandfather once said that the farm where he was born was not the original family home. The Donohues (the original spelling) were from Killarney. During the Great Hunger, or perhaps in the aftermath, they wandered north, and eventually found abandoned land in Tuam, Co. Galway. I don’t know exactly when this was, if there was an actual house, or the barest remains of one, if they knew the fates of those who’d lived there before. If they were even able to care by then. What they surely understood–nobody was coming back.

Read more

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments