The Irish history spread far and strong and the honor of the 3rd annual Big Irish Campfire, the first African American child in the state school system, Sonnie Hereford IV from Alabama, is a member of the community worth celebrating.

As I left an evening reception at the Huntsville home of Michael and Lisa Bollinger, mainstays of the most active chapter of the Ancient Order of Hibernians in Alabama, I thanked them for putting out the Tricolor in my honor. "That's not for you," said Lisa, letting me down softly. "That flies every day."

There would be no surprise to see the Irish flag fly proudly from a porch in Massachusetts or New York but in Rocket City it's more of a rarity, reflecting the fact that the Catholic population (where most but not all Irish find a home) of the state barley stretches into double figures and the Irish portion of that figure is smaller again.

Throw in the fact that the racism once synonymous with the Heart of Dixie swept up the immigrant Irish Catholics and you have less than fertile ground for Irish Americans to thrive. Nevertheless, the heart of Irish America beats here too.

There are, for sure, plenty of Irish and Scots-Irish surnames in Alabama: 'Bull' Connor who enforced the racist segregation laws of Birmingham had undoubtedly Irish Catholic ancestors though he himself was an unlikely Sunday school teacher; Rosa Parks, who refused to sit at the back of the bus and sparked a revolution, was a McAuley to her maiden name. However, more potent is the Irish heritage of those who came to the state from the Irish heartlands of America.

A sizeable number of the Irish American networks in the state are led by blow-ins. Marty Connors, President of the Birmingham Irish Cultural Society, hails from Kentucky, though he's been a lifetime now in the Magic City. Michael Bollinger's roots are in San Antonio, long a stronghold of the Irish, while Lisa grew up in Dansville, NY. And as Huntsville, home to NASA's George C. Marshall Space Flight Center and a major military presence overtakes Birmingham to become the state's biggest city, it is proving a magnet for talent - much of it Irish.

At a gathering in Maggie McGuinness', a 'homely' Irish pub in the Bollingers' basement no less, I met a Shaughnessy, a King, and a Docherty, all of whom had come south to Huntsville for work. In the absence of an Irish center, Maggie McGuinness' has become the go-to place for Irish American events; a planning hub for the annual St Patrick's Day parade hosted by the Irish Society of North Alabama, séisiún venue and a gathering spot for the Fr Trecy division of the Hibernians.

The shutters came down on Maggie's when the Covid storm hit and both 2020 and 2021 were no-shows for the St Patrick's parade but, slowly, the Irish are emerging from the pandemic lockdown with firm plans to return to the streets for the 45th time the Saturday before 17 March.

"Although the Irish community in Alabama is small compared to other areas there are strong pockets of Irish activity bringing together Irish transplants to Irish Americans to Irish enthusiasts," explains Irish Echo subscriber Michael Bollinger. "Pre-Covid, Maggie McGuinness' hosted several Irish bands who also performed out and about as well as traditional sessions with local musicians. During many of those sessions, Irish dancers from Alabama Irish dance schools joined in. And, at one point the local area had a seanchaí from Ireland, who unfortunately passed some years back, but graciously told many stories in the pub. The Alabama Irish community is small but we are active and proudly keeping the Irish Heritage alive."

Birmingham, Alabama will be forever associated with the civil rights struggle of the sixties, and in particular, with the fearsome bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in September 1963 claiming the lives of four young girls. While the city's mayor Randall Woodfin declared last month in the inaugural speech kicking off his second term that "we are not our past", it is the city's position as crucible of the civil rights struggle which gives Birmingham a global stature.

The Irish of course have been in Birmingham since the city was established by northern industrialists in the late 19th century. Today, the mantle of Irish America is carried by the Birmingham Irish Cultural Society under the leadership of Marty Connors. When we met at Fife's famous breakfast eatery (two eggs over-easy and grits for just $8:25), the Society President was ramping up his sales efforts for the 42nd annual St Patrick's gala featuring Westwood Irish Dancers and Black Market Haggis, the latter, thankfully, a band rather than a foodstuff.

"Some folks may be surprised that we exist at all in the Deep South," says Marty Connors, only partly tongue-in-cheek. "But we do exist."

"This year will mark the 37th year of our St. Patrick's Day parade through the Five Points district and while it’s not Chicago, New York, or Savannah, the parade has evolved into the largest retail day of the year in the community."

Connors acknowledges that you have to dig a little deeper to discover the Irish of Alabama.

"Apart from the romanticism of Scarlett O’Hara and "Gone With the Wind", Irish visibility in the Deep South is not as easily recognizable as many northern and northeastern cities but it’s there," he insists. "We don’t have the Irish neighborhoods but we do have the occasional pub here or there. In the south, Celtic culture is more sublime — subtle but every bit as much the stew broth that represents the full taste of Celtic culture. Music — country, Appalachian, bluegrass — dance — clogging, square, line — whiskey (with an 'e') is very much a part of southern life. Ingrained, you might say. The same applies to surnames. In a sense, the south is very much a melting pot of Celtic and old European cultures without the neighborhood flags."

Over recent years, Marty Connors has teamed up with tireless Birmingham ambassador Mark Jackson to test the potential of a sister city agreement with Derry City — the birthplace of Ireland's civil rights movement. And while that relationship has yet to be consummated, there is continuing outreach between the two cities, including the prospect of a link between 16th Street Baptist Church and the Museum of Free Derry. For Connors, business can step in and make hay once cultural, educational and arts friendships have been forged.

"The southern United States is the fastest growing, lowest-taxed part of the nation but is routinely missed by Irish developers more comfortable with the familiarity of the old family’s new American home. Biotech, engineering, space, logistics, automotive, shipbuilding, healthcare, and academic research, it’s all here and the waiting lines are not nearly as long. So, my message to Irish economic investment agencies and cities is that is wise to include teaming with a southern Sister City or similar network as part of an Irish diaspora strategy."

Though more English than the English - he can trace a direct connection to Henry VIII — entrepreneur Mark Jackson is the mighty river into which all the Irish tributaries in Alabama stream. Like many other Irish patriots, though, he can claim to be Irish through marriage! Mark's wife Allison can trace her own roots to Co Antrim through her Cork (maiden name and county) lineage. Together, the pair have put Ireland on the map in Birmingham, arguing passionately for that Derry-Birmingham sister city relationship and hosting the late Northern Ireland Bureau director Norman Houston in their home.

They similarly rolled out the red carpet for this Irish pilgrim, bringing together an eminent group of Birmingham change-makers to discuss challenges common to both Belfast and the Magic City. Those parallels, of course, include our troubled past — though do not be surprised if most folks in Birmingham are unaware of any links between those civil rights struggles. One local businessman confessed to me that he had never previously thought of the 'Troubles' in the North of Ireland as bearing any relationship to the Birmingham battle for equality but then during a visit to Cape Town, South Africa he was also taken aback when locals declared his hometown and theirs had undergone similar journeys. "I'd never thought of it that way," he said.

All of this reminds me of the story told by Belfast Presbyterian peacemaker Rev Steve Stockman who was being feted by his white hosts in the rarefied atmosphere of the Mountain Brook Country Club looking down on the city. "Tell me now, Steve," said the head of the local welcoming party, "what's it like to live in a segregated city?"

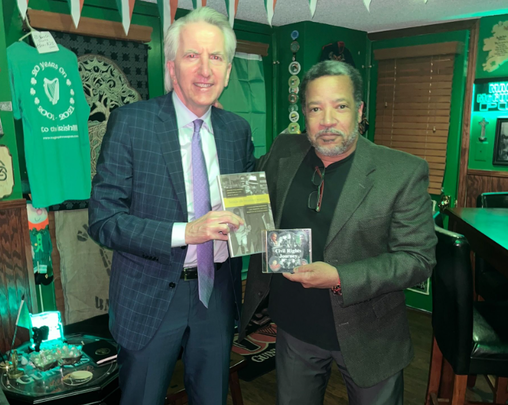

Sonnie Hereford

That tale, one suspects, won't come as a surprise to Sonnie Hereford, a lynchpin of the Irish in Huntsville and also the first African American child to enter the public school system in Alabama - a feat that took a father with the heart of a lion and a Federal intervention.

A graduate of Notre Dame and senior systems engineer (an honest-to-goodness rocket scientist to you and me), Sonnie organized the St Patrick's Day parade in Huntsville for a full 16 years (1996-2011) and remains an unabashed fan of all things Irish. He is also a scholar of the civil rights movement in Alabama who lived through years of tumult and change - change enough to see a school in Huntsville named after his father who memorably quipped, “They used to call me names now they name schools after me.”

It may be some time before Huntsville or Birmingham can compete with Boston, Buffalo, or Chicago for the title of the capital of Irish America but for sure the Irish have a bridgehead in Alabama.

Equally, forever linking Ireland with Alabama will be the civil rights protests and anthems born there and later transplanted to Belfast and Derry. Sonnie Hereford is the living embodiment of that link but so too is the only Irishman featured among the powerful exhibits at the world-renowned Birmingham Civil Rights Institute: Fr James E. Coyle. An Irish immigrant to Birmingham at the turn of the last century, Fr Coyle endured harassment from the Ku Klux Klan which culminated in his murder outside the Cathedral of St Paul after "he married a dark-skinned Puerto Rican man and a white woman". The shooter, the Rev Edwin Stephenson, was the father of the bride and an ardent Klansman — subsequently set free by the courts. Regardless of formal agreements, who would deny, on this the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, that Birmingham and Derry are indeed sister cities?

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments