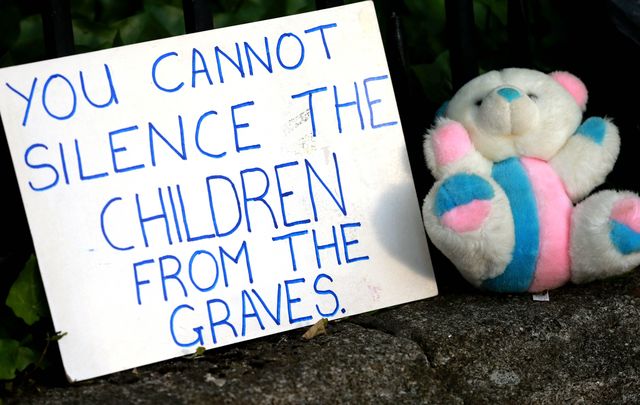

A Northern Irish forensic archaeologist is helping families locate the unmarked graves of stillborn children throughout Northern Ireland.

Toni Maguire, 66, has spent the best part of 20 years identifying sites in Northern Ireland where stillborn children were secretly buried. Maguire, who obtained a degree in archaeology from Queen's University Belfast in the early 2000s, began identifying unmarked graves as part of a college project and quickly became engrossed in the work.

The project was deeply personal for Maguire, who had miscarriages during her first two pregnancies.

"It just struck a chord with me," Maguire told NBC News.

Maguire said that she didn't know where her unborn children were buried as the hospital had disposed of them and said that she could resonate with families seeking to locate the graves of long-lost sons, daughters, brothers, and sisters.

"It never leaves you," she said.

She quickly developed a knack for discovering long-lost burial sites also known in Irish as cillini (little churches). Within months of starting her college project, Maguire had discovered 97 cillini across Northern Ireland. Only 11 sites had been recorded before she undertook the project.

However, the scale of Maguire's work changed irreversibly in 2008 when she was given access to the mass burial site at Milltown Cemetery in West Belfast.

Up until that point, the forensic archaeologist had focused on locating sites where one or two infants had been buried in secret. Milltown Cemetery, however, contained thousands of remains in a sprawling mass burial site.

The mass burial site was attached to the main cemetery and was the source of a major controversy in 2008 when the cemetery trustees sold off the land containing the unmarked graves.

Facing significant public backlash, the Diocese of Down and Connor reversed the sale of the mass burial site and allowed Maguire to map out burial plots at the site.

She enlisted the help of Dan Skelly, a North Belfast resident who had worked as a gravedigger at Milltown Cemetery for decades, and the pair quickly began tracing down children's final resting places.

Skelly has worked at the cemetery since turning 17 and can recall how babies were unceremoniously dumped in burial sites measuring nine feet by four-and-a-half feet. Each pit could contain hundreds of remains, Skelly told NBC.

"At that time, some of the undertakers used to collect the babies out of the morgues, bring them up in shoeboxes, cardboard boxes. Some of them had coffins, some didn’t," he told NBC.

"If a parent came, they’d bring the parent down and let them see the child getting buried, but other than that the shoebox would just be put on the back of the tractor, taken down and buried."

With Skelly's help, Maguire was able to locate the remains of stillborn children or of children who died at a very young age by sorting through birth and death certificates in addition to burial records and archives from mother and baby homes in Northern Ireland.

She has become renowned in the local community as someone adept at tracing the final resting place of children who died at birth and has received a steady stream of requests from family members desperate to find their relatives' graves.

Maguire often spent six days a week at the cemetery while completing a masters' degree in anthropology and helped track down the final resting places of countless children.

Not every search has been a success, however, and Maguire remains haunted by her failure to locate one particular child.

"It bugs me still that we can’t find that baby."

Despite working at the site for years, Maguire has only managed to locate a small fraction of the babies buried in unmarked graves at Milltown Cemetery.

Nevertheless, she has helped bring closure for hundreds of families since beginning her work in late 2008.

Kathleen Chambers, for example, had spent the last 57 years wondering where her first-born son had been laid to rest before she contacted Maguire by phone.

Within weeks, Maguire had located the site where Kathleen and Jim Chambers' son Gerard Joseph was buried in the cemetery 57 years ago.

"I was allowed to grieve," Kathleen Chambers told NBC. "It’ll never close as far as I’m concerned, but at least we were able to go and actually say we had a son and this is where he was. … I’ll owe Toni a debt for the rest of my life."

Gerard Joseph Chambers lies in the middle of the 5.9-acre mass grave and his final resting place is now marked with a heart-shaped headstone. His headstone is one of dozens of stones at the mass burial site and Maguire believes that knowing the final resting place of the children born at the site can help bring people closure.

"All people really want to do is find their family." It’s like having a lost child. You can’t settle until you know where they are."

Comments