Patrick Radden Keefe’s best-selling book uses Jean McConville’s disappearance to open a forensic examination of Northern Ireland’s Troubles but his critical insight is lacking and is very much flawed

“Say Nothing” the best-selling book by Patrick Radden Keefe, is initially about the horrific abduction of the mother of ten Jean McConville in December 1972 in Belfast by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Radden Keefe uses the McConville disappearance as the opening act in a lengthy forensic examination of The Troubles. The prose and narrative are superb even if the critical insight is lacking.

As for Radden Keefe, he was born in Boston, not especially attuned to his Irish roots, he says. Of course, he has to tell the tale of the local bar with the jar for the IRA collection that his father claimed to see. I chased down that urban myth as well as I could some years back. There was one bar the Plough and Stars, in San Francisco, that actually definitely had a jar, ironically for the Official IRA, a far-left group. Every other report I could trace was bogus.

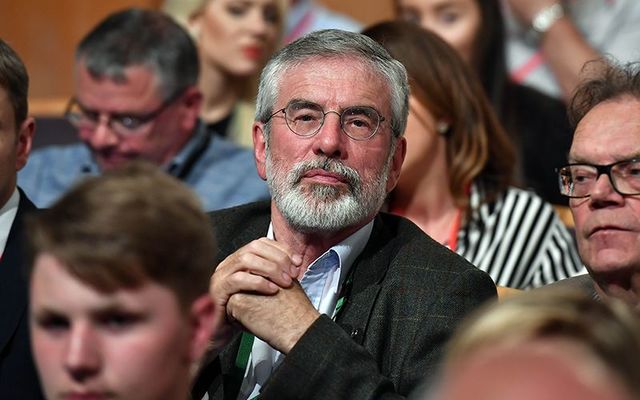

The book, like the IRA collection story, is seriously flawed. There is no interview with Gerry Adams, a central figure in the narrative. The book is also highly misleading as to the real purpose behind the now infamous Boston College Belfast project tapes, which inform a large part of the book’s narrative.

Radden Keefe had made his dislike of Adams very evident in the New Yorker article of 2015, which was the springboard for the book and soon a television series on FX.

At one point in The New Yorker article, he relates in almost racist language that the “brute came out” in Adams at a New York dinner where he had the temerity to joke about shutting down Independent Newspapers, a rabidly anti-Sinn Féin newspaper which fed out anti-Adams propaganda for years. I was there on the night and remember clearly the remarks were certainly not considered in the least incendiary by those present, knowing the context.

Knowing the context is key to writing about Northern Ireland and Radden Keefe either does not know it or refuses to acknowledge it.

He presents the disastrous Boston College tapes episode as of major significance without any sense of what was really going on. Two avowedly anti-Adams journalists and researchers convinced Boston College into believing they were delivering even-handed interviews of historical value of major combatants in the North.

Ed Moloney, journalist and author had long harbored deep antipathy towards Adams while Anthony McIntyre had joined a dissident group of former IRA men in protest against the Adams peace process policy and wrote regular anti-Adams screeds.

Saint Ignatius Loyala statue in front of Boston College building.

Not surprisingly, it was actually a get Adams exercise. It now appears there were 26 tapes of leaders from The Troubles of whom 24 were anti-Sinn Féin and Gerry Adams. You will not read that in Radden Keefe’s book.

The project came apart when Northern Ireland police demanded the tapes. The subjects thought they had been assured of protection with a promise the tapes would only be made public after they died.

All hell broke loose. Five Boston College history professors signed an open letter headlined: "'Belfast project' is not, and never was, a Boston College history department project."

A spokesman for Boston College, Jack Dunn confirmed the project was ill-conceived and amazingly, took Adams's side.

Dunn made an extraordinary attack on his own college's choice of researchers.

“Gerry Adams and others have accused Anthony McIntyre of interviewing individuals who had animus towards Adams and the Sinn Féin leadership. Gerry Adams’ criticism of Ed Moloney and Anthony McIntyre is shared by many on both sides of the Atlantic,” Dunn said.

“While some mistakes were made by Burns librarian Bob O’Neill, his sentiment is that the biggest mistake was in hiring Ed Moloney, who ultimately hired Anthony McIntyre... He did not vet them enough.”

That is an extraordinary disavowal but there is next to nothing in Radden Keefe’s book about it. He treats the tapes and their accusations as gospel. He never reveals the true intentions of Moloney and McIntyre and the book’s content is severely flawed as a result.

The animus against Adams did not stop with Moloney and McIntyre (who is affectionately described as “Mackers” throughout the book), Northern Ireland cops, securocrats, and MI5 had longed to get a conviction of him. The BC tapes appeared to offer a way

The Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) got possession via a court order and arrested Adams for the McConville murder based on the hearsay of a dying man, Brendan Hughes, who had fallen out badly with Adams and was deeply antagonistic to him.

Adams spent four days in jail as a result of the tapes but unsurprisingly, was released without charge. The Boston College tapes were an all-out attempt to get Adams which almost worked.

Radden Keefe also sends up the usual balloon of why Adams would never admit he was in the IRA. In truth, Adams should probably have come clean before the peace process but the danger of him admitting it subsequently was lost on Radden Keefe.

As the Boston College attempt to incriminate Adams showed, admitting to membership would have given an open playing field to his myriad enemies, not to mention British and Northern Irish police, and every IRA action from that period would have been re-examined in an attempt to jail Adams. No Adams, no peace process.

Like the Boston College tapes, almost all the author’s sources in the book are Adams enemies, including Richard O’Rawe who wrote “Blanketmen” a direct shot at Adams and his conduct during the hunger strikes.

Chief among the Adams haters are the legendary Price sisters, Dolours and Marion, both of whom rejected the IRA ceasefire. These participants share an animus towards Adams for stopping the war and focusing on political progress.

The lack of a balancing voice making the case for the Adams strategy of a negotiated peace is a major defect.

One wonders if the irony of his position ever struck Radden Keefe, listening and recounting the tales of the warmongers while failing to balance with the voices of peacemakers, which was the stark situation on the ground. The battle within the IRA between hawks and doves was ferocious Radden Keefe tells only one side of it.

In a strange twist, towards the end, Radden Keefe about as much accuses one of the Price sisters of carrying out a dreadful act related to the McConville case. The accusation is delivered based on hearsay and speculation and should never have been made.

Finally, Radden Keefe is surprised that Adams can seem so much at ease with himself despite the dark days of The Troubles. That happens when a man fights back against an oppressor and wins a peace settlement no one thought possible.

By focusing on those who did not want peace and their allegations this book is deliberately misleading as to the fundamental truth of the time.

Adams and Martin McGuinness achieved what no previous Irish Republican leaders such as Michael Collins ever had, taking an armed insurgency and putting it on a political path. That was the ultimate achievement.

Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness.

As Richard O’Rawe, an avowed Adams opponent, admits, “Without him (Adams) and the hunger strikers there would be no semblance of peace in Ireland today.”

A final note on the book Radden Keefe does articulate very well the pain and travails of the McConville children after their mother was snatched from them. Those were horrific times as the story this week of the arrest of a British soldier who shot Daniel Hegarty, an innocent 15-year-old, twice in the head in Derry in July 1972 attests to.

As always in the North, the past is present which makes it vital any serious account of it is true to what happened. “Say Nothing” fails that test.

Comments