Foreign policy rarely figures as an important factor for voters in peacetime American presidential elections. Polls suggest that this year is not an exception.

*Editor's Note: This letter to the editor appeared in the August 26 edition of the Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral.

The coronavirus and its impact on jobs and education top American voters’ concerns, followed by the serious agitation for change in the area of race relations and, finally, more concern than ever about the worsening economic inequality in the country.

These are the main issues that will drive turnout in November. America’s standing in the world is at its lowest in recent memory, but that is not showing as a major worry in any of the polls.

If Joe Biden emerges victorious he will inherit a dismal world order, with the standing of the United States in the doldrums. This will require major bridge-building strategies by a new administration.

President Trump has little positive to show in international affairs as he completes his first term. He seems to be unwilling even to read his daily briefings on world events.

Recently, he confused the aftermath of the First World War (1914-1918) with the Second (1939-1945). During his years at the helm, North Korea has enlarged its deadly arsenal, Iran has resumed its nuclear program, Nicolas Maduro has tightened his control in Venezuela, and China’s mixture of capitalism and autocracy has led to real economic gains that have earned them plaudits in many countries.

If Biden takes over in January, his first priority internationally will involve restoring this country’s credibility in European capitals with our most valuable friends for 75 years. Prior to the Trump era, London, Paris, and Berlin were America’s closest and most dependable allies.

The United States was drawn into the two world wars in the first half of the last century. They were reluctant participants and only got involved more than two years into each conflict because in both wars the mood of the country trended strongly towards isolationism. The cry to let them fight their own battles “over there” resonated with a majority of Americans.

After the Allies’ victory in 1945, Europe was in ruins. Americans led by President Harry S. Truman and Secretary of State George C. Marshall were determined to do everything possible to avoid being drawn into another European conflict. They complained that Washington had no interest in settling nationalist grievances dominated by princes and popes in what they spoke of as the Old World.

President Harry S. Truman. (Public Domain)

Marshall, in particular, learned from the Treaty of Versailles, which ended the First World War but humiliated the defeated Germans by imposing annual hefty reparation payments and restricting their industrial re-development – a very understandable reaction after the mayhem and savagery of trench war. However, this approach planted the seeds for another war that cost around 75 million lives just 30 years later and ended in the Pacific with the first and only belligerent use of nuclear weapons.

Marshall, recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953, was a visionary leader who decided to steer clear of punitive actions against Germany and the other defeated Axis powers. Instead, in a recovery plan that carries his name, he persuaded the leaders in Washington to provide generous funding for infrastructural and industrial development projects throughout Europe.

US Secretary of State George C. Marshall. (Public Domain)

This was Marshall and President Truman’s magnanimous answer to the failed Versailles strategy. It represented a serious change in political thinking and was named the Truman Doctrine, or more grandiosely, Pax Americana.

As well as the major financial help that came with the Marshall Plan, Washington encouraged mutual support organizations in Europe. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), started in 1949, was a strong military alliance that laid the groundwork for the containment of communist Russia.

Supported by the United States, they warned the Soviet Union -- and after its collapse in 1991, the new leaders in Moscow -- that westward territorial expansion to any NATO country would result in combined military retaliatory actions. So, for 70 years the threat of a massive united armed response has successfully curbed any military intervention into the 29 NATO countries.

In 2014, Vladimir Putin invaded the Ukraine and annexed the Crimean Peninsula. Western leaders, led by President Obama, protested vigorously and expelled Russia from the elite group of eight countries (G8) that meet every year to deliberate and seek consensus about the various major issues facing the world. While Ukraine is not a member of NATO, Putin’s naked show of force shocked political leaders everywhere.

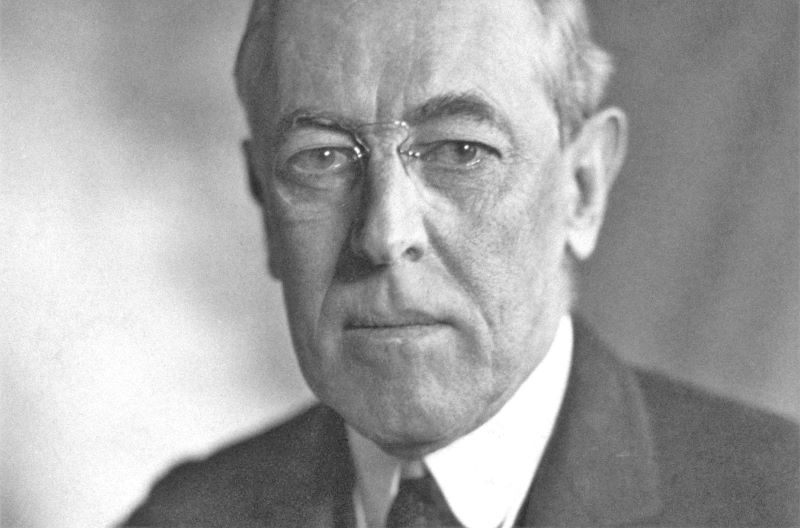

The League of Nations, which was formed after the First World War, turned out to be ineffective mainly because the U.S. Senate, suspicious of ceding power to any outside body, never supported it, although the terms of the new alliance were largely drawn up by President Woodrow Wilson.

President Woodrow Wilson. (Public Domain / US Library of Congress)

After another world war calamity, the United Nations was founded in 1945, this time with full support from American leadership. The goals were the same as for the League – stressing negotiations to solve conflicts and endorsing all efforts to root out the causes of war especially poverty and xenophobia.

The third leg of the cooperative stool emerged with American prodding as the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) in the early 1950s. The agenda of the ECSC focused on economic cooperation between members for the benefit of all the countries involved.

This new spirit in Europe proved successful and the membership has greatly expanded into what is now the European Union, with membership of over 470 million, all committed in accordance with the agreed rules, to a free-market democratic form of government. Even without Great Britain, which opted out of the EU last year, this is the largest and richest trading bloc in the world.

These three pillars of progress -- the UN, the EU, and NATO -- are under serious attack and diminishment by the current administration in Washington. All previous presidents since FDR have given unequivocal support to each of these organizations, seeing them, quite rightly, as central parts of a universal political and economic order benefitting the United States.

President Trump’s narrow war cry Make America Great Again (MAGA) leaves little room for multi-national organizations. He has denigrated NATO, publicly berating the German and French leaders, Angela Merkel and Emmanuel Macron, and lowering the Washington contribution for funding the alliance. In addition, the American president is seen regularly cozying up to Putin, who is disliked and distrusted in European capitals.

The UN has received a similar cold shoulder from the Trump White House. The current president decries what he sees as moves towards world government, a favorite bête noire of many conservatives. In addition, he is demanding that the organization should dismantle the 2015 Iran Nuclear Agreement, the product of years of negotiation with six major world powers led by President Obama.

During the heated Brexit debate, Trump rejected his predecessor’s urgent plea to the British people to remain part of the alliance. Instead, he urged them to break with Europe and promised a favorable trade deal with the United States. He warned European leaders that if they don’t agree to “reasonable” trading terms with Washington, he will impose high tariffs on goods, including cars, exported for the American market.

If Trump is re-elected the current shaky alliance between the United States and Europe will deteriorate further. If Biden takes over in Washington, the close relationship initiated by George C. Marshall after the end of the Second World War will again dominate the thinking on both sides of the Atlantic.

Another reason why the presidential election in November is hugely important.

You can read more from Gerry O'Shea on his blog, WeMustBeTalking.com.

Comments