How the Irish celebrated Thanksgiving in New York and dressed up as ragamuffins.

It is just after World War II. Boundless optimism sweeps across America – the undisputed leader of the world. Our family attends the 9 o’clock Mass at Sacred Heart Church in the Highbridge section of the Bronx. It is Thanksgiving morning.

“I’m telling you," my mother declares when we return home, "When your father sailed to New York from County Sligo in 1928 at age 22, and I landed here from Leitrim a year before him at age 16 all by myself, we had no idea about Pilgrims or Indians, turkeys or chestnuts."

Mom bends down smudging charcoal on my face and on my older brother Johnny's cheeks. “Here,” she says, “this will make you look like ragamuffins. Put on these old patched pants and Daddy’s old fedora. Push up the rim, bend it sideways like a vagabond.”

Read more

She stands back, surveying us, making sure we look like street urchins. “Off you go now and be back before the company arrives.”

We joined our fellow kid ragamuffins knocking on doors, ringing bells of apartments in our Bronx neighborhood as we hold out our little purses and chant, “Anything for Thanksgiving? Anything for Thanksgiving?”

Some Thanksgiving Ragamuffins, photographed circa 1910 to 1915. Not so different to our Halloween.

We take in the warm, delicious smells of turkeys cooking and cakes baking wafting from each apartment. People drop a few pennies in our bags, an occasional nickel or a candy treat, and some even hand over empty bottles for us to collect the 2 cent deposit. In the end, we compare our bounty with our fellow little beggars and celebrate with a mini feast of our own at Julius Negoff’s candy store buying chocolate turkeys and candy corn.

This begging as ragamuffins on Thanksgiving Day became a forgotten tradition by the 1950s replaced by trick-or-treating on Halloween. By that time our Thanksgiving mornings were taken up with touch football on the streets followed by watching the annual football game between the Green Bay Packers and the Detroit Lions on our black and white 13-inch Emerson TV.

By mid-afternoon of Thanksgiving Day, our Irish aunts and uncles and cousins arrive for the big dinner. They come clomping up the stairs to our 5th-floor apartment, Cushman’s cakes in hand. My mother’s brother John and his family arrived along with Mom’s sister Margaret and her family, and my father’s sister Amelia with her family, and just off the boat from County Sligo, my father’s 20-year-old niece Dolores McLoughlin who has come to live with our family in New York.

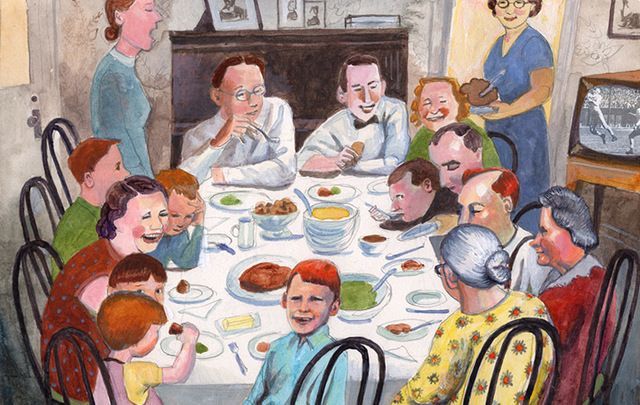

All are greeted heartily, the men in shirts and ties, the women in their Sunday best and all the cousins together again. After drinks served by my uncle John, who is the bartender at the local Leo Sullivan’s Saloon, we all settle down for the big meal. At the table, we look a bit like the family in Norman Rockwell’s painting of a bountiful Thanksgiving, though I knew nothing of that famous picture in those days. The picture we had hanging on our wall was Millet’s painting of The Angelus — two peasants, a man, and a woman, bowed in a noon-time thanksgiving prayer in the middle of a potato field.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Few activities my mother enjoyed more than that of the hostess of a dinner party for friends and family. She joyed in bringing people together, serving them their favorite cocktail, providing plentiful food and stimulating conversations between people. Once seated at a table heavy with turkey stuffed with mushrooms, whipped sweet potatoes with marshmallows, green beans with almonds, mashed turnips, and juicy cranberries, one of the guests invariably would say:

“Ah, Mamie, will you ever sit down and join us and stop your running around taking care of everyone else?” And Mom would reply as she serves up yet another dish of vegetables, “Ah sure, I like it this way. Let you all just sit back and enjoy yourselves and I’ll take care of myself, don’t you worry. Here, Bernard, let me refill your glass while I’m at it, and I have creamed onions coming up so leave some room!”

And, of course, no Irish get-together was complete without the talk of politics. My father and my uncle Frank both worked on the “railroad,” which was how the Irish referred to the IRT subway system. Both men adored their firebrand Irish union leader, Mike Quill. “Did you hear Mike’s latest?” my father says, “City Hall told Quill to calm down and he answered in his thick Kerry accent, ‘The Bible says, “The meek shall inherit the earth,” but I say to ye, The meek shall inherit nothin.’” Throwing their heads back in laughter, Uncle Frank and Pop lift their glasses, “Go get ’em Mike!”

I most recall the time in the early 1950s when we received news that a 20-year-old Irish “greenhorn,” a very good friend of the family, had been killed in action in Korea. My father brought the table to silence as he railed against that war, “Here’s this fine, young, educated lad from County Cork only in New York a few months before he is drafted into the U.S. Army, and then a few months later he’s dead! We never should have gotten into that lousy Korean war!” My father looks to my uncles for support. And here is my Uncle Frank, himself a World War II veteran drafted into the U.S. Army soon after he arrived from County Cavan in the late 1930s. And there sits my Uncle Bernard McEvoy, drafted in his mid-30s to serve in the U.S. Navy during World War II. Both served proudly and say nothing in response to my father except to shake their heads at the tragedy of this young Irish boy’s death.

“Isn’t it the way with these holidays,” my aunt Vera, a Roscommon woman, pipes up. “Always some tragedy or other taking place. But enough with all this sadness. Let’s have some music!” With that my father picks up his fiddle and plays a few tunes, always starting with the “Stack of Barley” the original Irish melody that gave birth to the American classic, “Turkey in the Straw.”

My mother then sings a ballad about an Irish country lad, Willie, who falls madly in love with the beautiful Annie. Wrenched from her arms by the cursed English army, Willie is sent off to fight in the Napoleonic Wars. After a long time passes, the dejected Annie, fearing her love has been killed, falls ill from heartbreak and takes to her bed just as the young soldier fights his way back to Ireland, finally arriving at her door. Mom always takes a pause near the end of this ballad letting the room fill with hushed suspense before she intones the fateful and final words of the song: “And he found she was dead!

“At that point, someone invariably takes a long drag on his cigarette filling the room with smoke, and murmurs, “Ah lovely, Mamie, just lovely! God bless ya.”

With the Irish — I came to realize fairly early on — the sadder, the better! Especially when it came to love and patriotism. Blood and guts, martyrdom and death — the Irish could not get enough of it. G.K. Chesterton summed it up best when he wrote:

The great Gaels of Ireland are the men

that God made mad,

For all their wars are merry, and

all their songs are sad.

More songs followed by the aunts and uncles and even the young cousins. My cousin Vincent Gallagher sings “Galway Bay” in his best Bing Crosby voice, and I sing, “The Same Old Shillelagh Me Father Brought from Ireland.” There are Irish songs of courtship, of motherly love, of the beauty of the land, of homesickness as well as good old-fashioned Irish and American patriotic songs. And funny songs like “Eliza’s Two Big Feet,” and “Paddy McGinty’s Goat” – famous for eating up Kate’s “folderols” upon her wedding night.

On special occasions, my father even recites a favorite American poem, “The Face on the Barroom Floor.” And then there was Paddy O’Donnell, a next-door neighbor, who we hardly spoke to from one end of the year to the next, but who never failed to show up after the Thanksgiving meal to sing:

Bless this House Oh Lord we pray,

Make it safe by night and day.

Bless these walls so firm and stout,

Keeping want and trouble out

Bless the hearth

Ablazing there

With smoke ascending

Like a prayer.

I should add that no “a blazing hearth” was ever found even near our Bronx walk-up apartment, but Paddy – despite his quavering high pitched voice – always manages to instill a silent reverence as the merriment of the evening slowly winds down.

As Uncle Bernard takes his leave at the door, he crushes a dollar bill into my hand and shushes me to silence lest my parents insist I give the money back. The aunts, uncles, and cousins, with hugs and kisses, bid good-bye more than once before they all go off into the end-of-the-year cold night air until the next time.

They are all long gone now: my Irish mother and father, and all my aunts and uncles. A brave generation of Irish men and women — Pilgrims in their own way — who came to America in the 1920s and 30s and are no more.

On the edge of sadness, we remember them with a grateful heart.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

* Michael Scanlon, an English lecturer, is the son of Irish immigrants and grew up in the Bronx, NY. Now aged 77, he has published a book on his life growing up in Irish America. “Rolling Up the Rug: An American Irish Story” is available on Amazon.

** Originally published in 2015. Updated in November 2015.

Comments