David Trimble had an extraordinary beginning in Northern Ireland politics. He joined Vanguard, a crypto-fascist movement that was intent on ethnic cleansing Catholics from Northern Ireland and was led by Ulster’s very own little Hitler, William Craig.

Craig was the most militant figure in Northern Ireland between 1972 and 1978. He had many close links with loyalist paramilitaries, as did Trimble, who became deputy leader of Vanguard and one of its most hardline members.

To make the leap from a neo-fascist organization to Northern Ireland’s original first minister, and to win the Nobel Peace Prize, is one of the most extraordinary transformations in British or Irish history.

Yet Trimble evinced none of the warmth or progressive political leadership that marked other notables of the time such as John Hume, who was the co-recipient of the Nobel Prize with him.

David Trimble and John Hume. (RollingNews.ie)

Put simply, Trimble was hard to like. He was arrogant, domineering, and made some remarkable faux pas, including leaving a dinner in Northern Ireland for President Bill Clinton, saying he had to catch a plane to Italy.

March 17, 2000: US President Bill Clinton, second from right, with Sinn Fein President Jerry Adams, left, Social Democratic Labor Party Leader, John Hume, second from left, and First Minister, David Trimble at the White House in Washington, D.C. The three met with Clinton on St Patrick's Day to try to resolve current problems in Northern Ireland that have forced Britain to dissolve the Northern Ireland Assembly. (Getty Images)

But amazingly, when it came to that historic moment in that historic time, which we now call the beginning of the Irish peace process, it was Trimble who had the toughest job of all and who shouldered the greatest burden in bringing Ulster unionism into the 20th century.

After his time at Vanguard, Trimble joined the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) in 1978 where he was considered one of the most hardline members. There was genuine despair when he was elected leader of the UUP in 1995.

At the time, the burgeoning peace process was seeking a unionist leader capable of a great shift in thinking and, more importantly, bringing along the vast majority of unionists with him. That Trimble turned out to be the man who accomplished all that is one of the strangest stories in Irish history.

After joining the UUP, he became known for his belligerence against nationalists, most notably when he insisted that the Orange Order should be allowed to march to Drumcree through a Catholic neighborhood, a demand that almost caused the collapse of the peace process.

Despite all the negative press and the genuine despair, and the belief among Irish politicians that Trimble would never change, he went on to surprise everyone and took one of the boldest and bravest steps that any politician has taken in the history of Northern Ireland.

There were many contradictions in the man. But when Hume and Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams produced the Hume-Adams agreement, and the Irish government, British Prime Minister Tony Blair, and President Clinton all signed on, the crucial gap became the absence of a leading unionist voice to take a leap of faith.

Bertie Ahern, David Trimble, and Tony Blair in 1999. (RollingNews.ie)

Trimble emerged from a UUP leadership meeting in 1997 to announce that he was ready to take part in the great experiment in peacemaking. He was bitterly opposed in his own party, especially by Jeffrey Donaldson, who all these years later is still playing the part of obstructionist in the North.

What Trimble signed on to was that in return for a cessation of violence and satisfactory decommissioning of weapons, he would lead his party into government in a shared arrangement with the leading party on the nationalist side which at the time was the SDLP.

It was kind of step that no one expected of Trimble, who had been written off as a hopeless hardliner until that point.

Over the following years, he was attacked again and again by his own party and had to win several leadership votes, some very narrowly, as he continued to follow the path to the Good Friday Agreement.

When the peace deal was ultimately signed in 1998, Trimble became first minister of Northern Ireland, and in a truly historic moment, sat down with SDLP deputy leader Seamus Mallon to form a power-sharing government.

July 1, 1998: Seamus Mallon, Deputy First Minister, and David Trimble, First Minister, meet the press after their election by the new Northern Ireland Assembly at Stormont in Belfast. (RollingNews.ie)

There was another side to Trimble. He was a law lecturer at Queen’s University in Belfast, a man with great experience and world travel, an expert on opera and a highbrow book reader.

Trimble will rightfully go down in history as a courageous leader, irrespective of how difficult a person he was to deal with – and he was difficult.

But on the day that history dawned, he played his full role in making peace happen in Northern Ireland. For that, we can be forever grateful.

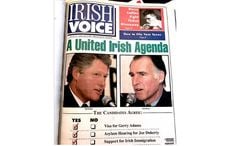

*This editorial first appeared in the July 27 edition of the weekly Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral.

Comments