Last week was another dizzying whirl on the Brexit merry-go-round, and it's all beginning to feel like Groundhog Day.

Taoiseach Leo Varadkar was in the North talking to the parties there. That night he was back in Dublin for dinner and private discussions with British Prime Minister Theresa May. Before that May had been in Brussels talking to the EU heads, as had Varadkar, but not at the same time. May had also been to the North.

On and on it goes, and nobody seems to know where we will be when the merry-go-round finally stops.

One thing is certain. There is a lot going on behind the scenes we are not being told about.

After each meeting, the leaders emerge and shake hands and smile and say their talks were constructive. And that's as far as they go.

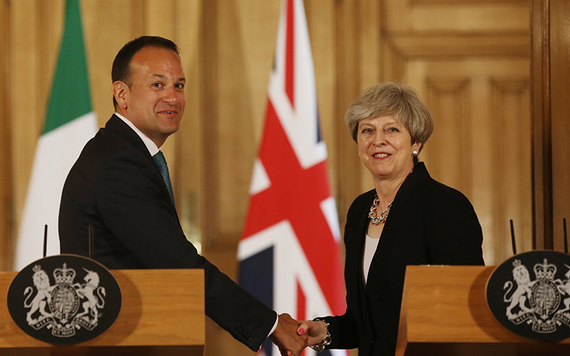

Taoiseach Leo Varadkar and Prime Minister Theresa May.

We are being kept in the dark about the real nature of the discussions, particularly about any efforts to find a compromise on the backstop -- the guarantee that there can never be a return of a hard border in Ireland, which is now the main sticking point.

The vague niceties and the repetition of basic positions is becoming tiresome. Everyone knows there has to be some kind of compromise if a hard Brexit crash-out is to be avoided which would mean economic chaos for everyone and, by the way, a definite hard border in Ireland.

If nothing is going on, why was the British attorney general in Dublin last week to meet his Irish counterpart? When the legal eagles are involved, you can be sure something is afoot.

But still we are being fed waffle, even as the efforts to unpick the conundrum intensify. Which is why last week's irritated outburst from the president of the EU Council Donald Tusk (who represents all the EU country leaders in Brussels) was so refreshing.

“I've been wondering what that special place in hell looks like for those who promoted Brexit without even a sketch of a plan on how to carry it out safely,” Tusk said.

He was, of course, referring to the Brexiteers like Boris Johnson who led the leave campaign in the 2016 referendum as a career move without a care in the world about the damage that might be done.

Tusk was, however, conveniently forgetting that the EU is just as culpable for the Brexit mess as Johnson and his public schoolboy cronies.

It's worth remembering this for a moment before we get bogged down again in the current state of play on Brexit. The main reason the U.K. voted to leave was immigration, particularly the very high level of immigration from eastern European countries.

Freedom of movement of labor (people), goods, services and capital are the "four freedoms" on which the EU common market is based. These four pillars were established under the 1957 Treaty of Rome and in the years that followed when only countries in Western Europe were members. They made complete sense in creating a common market and maximizing efficiency, and in the early years they worked since there was a rough economic similarity between the member countries.

But after 2004 that changed with the entry of so many new member countries in Eastern Europe where wages, welfare, the standard of living and so on were much lower. This led to large scale migration from Eastern Europe and in the last decade the first country of choice for these migrants has been the U.K., with hundreds of thousands of arrivals in some years.

Nor was it just the attraction of earning two or three times as much as they could back home. As EU citizens they had the right to all state benefits, including welfare, housing, education and health services.

For example, under EU rules a Polish worker could claim child benefit in the U.K. for his children back home, which at U.K. rates was sometimes enough to maintain his entire extended family in a village in rural Poland. What had made sense in the early days of the "four freedoms" was causing problems because of the wide disparity in development between Eastern and Western Europe.

The pressure this caused in the U.K. led to growing anti-EU sentiment over the past decade and the emergence of UKIP, the new party which wanted to leave and began to eat away at support for the Conservatives.

It was for this reason that the Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron took the fateful decision to hold the 2016 referendum with the intention of killing off the threat from UKIP before it got worse.

In the months before the referendum Cameron pleaded with the EU to allow him to put limits on immigration into the U.K. He pointed out that unlimited freedom of movement was unfair to the U.K. because so many people were coming from Eastern Europe. In the weeks before the vote, as the polls became alarming, he warned that without a concession the referendum could be lost.

The case made by Cameron made absolute sense. Unlimited freedom of movement was fine in theory, but in practice, it was premature because of the wide gap in living standards between Eastern and Western Europe.

Despite this Cameron got nothing from the EU, which stuck to the theory that the "four freedoms" were fundamental and could not be limited in any way. The result was that the leave side won the vote by a narrow margin.

And for that -- and the resulting Brexit mess we have been left with -- EU inflexibility is as much to blame as U.K. incompetence.

Having said all that, we are where we are, as our politicians like to say. The Brexit deadline is now just a few weeks away and no solution to the conundrum is in sight.

May is still sticking to her red lines -- that the U.K. must leave both the customs union and the single market if Brexit is to mean what the British people voted for. Ireland and the EU are sticking to the backstop guarantee of no hard border in Ireland. Both cannot happen.

The British Labour Party is now pushing for a much softer Brexit involving a permanent customs union with the EU and close alignment with the single market. That could make a hard border in Ireland unnecessary.

May is being polite about this, but is still sticking to the view that Out Means Out and the backstop must be time limited to prevent the U.K. being trapped in the EU indefinitely. Anything less won't get through Parliament, she says, and she is probably right about that since Parliament has sent her back to Brussels to water down the backstop.

She is still clinging to the position that a major trade deal can be done in the two year transition period (during which nothing much will change) which will make a backstop unnecessary. But the Irish government is not buying it and is continuing to take a hard line, dismissing U.K. suggestions about high tech solutions to create an invisible border if one becomes necessary.

Whether that is wise remains to be seen because for now the stand-off continues and the possibility of an accidental U.K. crash out is increasing.

And we should remember what that would mean for Ireland. If there is no deal then the border in Ireland will immediately become an external border of the EU.

We would have to protect the EU single market and customs union by hardening that border, collecting EU tariffs and enforcing EU standards on all goods coming in.

Let's take South American beef, an example we have mentioned here before. It's much cheaper than Irish beef but has limited access to the U.K. and European markets because of EU tariffs.

If the U.K. scraps these tariffs after Brexit and starts importing it on a large scale it will be devastating for Irish farmers. And that would only be the start of the problem.

Beef processors in the North who would switch to South American beef would be able to drive their beef products into the south for onward shipment to mainland Europe unless there is a hard border in Ireland to control trade. And it's not just beef -- Ireland could be a backdoor for all kinds of global products seeping into the EU tariff free.

That's the problem we would face. It would be the EU who would insist on a hard border in Ireland, not the U.K.

Hopefully all this can be avoided because the majority of politicians in the U.K. don't want a hard Brexit crash out. But accidents do happen and there is no sign of any solution so far.

Instead of endlessly parroting our No Hard Border mantra and ridiculing suggestions of a high tech invisible border, we should be preparing for the worst even while we hope for the best. And that may well involve exploring these high tech solutions.

Comments