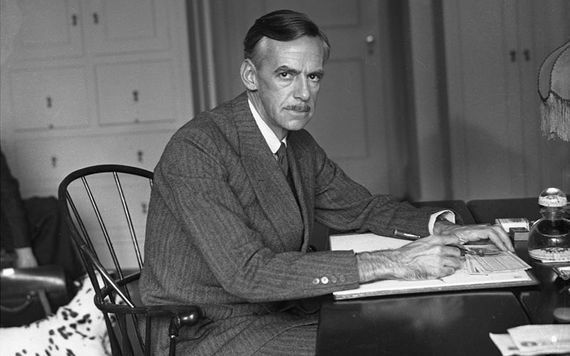

Acclaimed playwright Eugene O’Neill, a Nobel Laureate in Literature, died on this day November 27, 1953. We remember the "Long Day's Journey into Night" playwright by looking back on his most famous play and the parallels between this family and the Irish.

Although much honored in his US birthplace where his play “Long Day’s Journey into Night” is celebrated as one of the finest American plays of the 20th century, the work of Eugene O'Neill is somewhat overlooked in Ireland, despite him being the son of an Irish immigrant who writes about the role that emigration and Ireland played on his father’s character.

On this, the anniversary of his death, we remember O’Neill by looking back on his most famous play and the parallels between this family and the Irish.

O'Neill's father James was born in Kilkenny in 1847, in the darkest year of the Great Hunger. After a chaotic, poverty-stricken childhood (even after the family's emigration to America) he was left with a lifelong fear of the poorhouse. In 2016, "Long Day's Journey Into Night" played a run on Broadway, where Gabriel Byrne took on the part of James in one of the greatest performances of his career. Cahir O'Doherty looks at this intensely Irish play that the Irish themselves have yet to get to grips with.

Irish-American playwright Eugene O'Neill's father James was born in Kilkenny in 1847, the darkest year of the Great Hunger. He grew up in Ireland and America in a childhood that was filled with poverty and desperation.

That's probably why when O'Neill portrays his father as James Sr. in the bluntly autobiographical drama "Long Day's Journey Into Night" decades later, his life is marked by a lifelong fear of the poorhouse, one that haunts him in every scene of the play.

James' wife Mary is tormented by age and infirmity, but also by the past and by her deep fears for her youngest son's future. In fact, she's filled with so much foreboding over time she develops a drug dependency, addicted to the morphine that dulls her anxiety.

No wonder. The damage that has accumulated around this Irish-American family looks irreversible, the only question for the audience is exactly when the ax will finally fall.

Cheerful stuff, eh? Well, life isn't always beer and skittles and the Irish know this as well as anyone. That's why you can't really understand the full extent of O'Neill's achievement until you grasp just how Irish this heart shot family is.

In the 2016 Broadway production of "Long Day's Journey Into Night", staged by the Roundabout Theatre Company, Dublin-born actor Gabriel Byrne gave one of the great performances of his career as the penny-pinching stage actor James Tyrone, opposite Jessica Lange as Mary his long-suffering wife.

While it's true that Long Day's themes easily transcend the particular, its haunted Irish under-music, its defiant laughter and inconsolable resignation animate every scene. This story has started badly and most of the time that's the way it looks like it will end.

As James, Byrne played to every one of his strengths as an actor and an Irishman, onstage and off. It's a revelatory and at times naked performance from an actor who famously prizes his off-stage privacy more than most. But when the audience applauds and the curtain drops he prefers to return to his real life and his privacy, he says.

“I don't think I ever set out consciously to say, ‘Okay, I'm going to be really private in my personal life,’” Byrne tells the Irish Voice.

“But you do a job and there shouldn't be anything more demanded of you than the job. I also find it slightly invasive to feel that you're a product or a brand to be used, to be trotted out. I also think we're all entitled to our privacy.”

In our own celebrity worshipping era, not wanting to live in front of flashing cameras seems surprising to many, but not to Byrne.

“Now we're living in an age when people are beginning to understand that privacy is something that we took for granted. It's more and more difficult to retain it,” he says.

A lot more people seem to not want to be anonymous now that it's become harder to, he suggests. “I've never been comfortable with it, I've never sought it out, I don't go to multiple premieres or openings. I've done chat shows when I've had to do them.”

Don't expect him to be featured on TMZ or Hello! magazine anytime soon then. The trappings of fame aren't something that interests him.

“There are people who would go to the opening of an envelope and every time you open the paper there they are in a different dress. You think, ‘God, how can they do this?’” Byrne says.

“But you know what, I'm not saying anything against them, it's different for everybody. That happens to be my preference. I like it that way. I like being kind of anonymous.”

O'Neill won the Nobel Prize and the Pulitzer Prize for drama multiple times, but he's never included in our great Irish writer's lists. The Irish don't claim him, and worse, their theaters rarely perform his plays. Byrne, a longtime resident of New York City, has a theory as to why this is so.

“I can't remember the last time – I mean, there have been a couple of sporadic productions at The Abbey and Druid recently did one – we recognized Eugene O'Neill as the link between America and Ireland,” he says.

“Although this play is as Irish as Hamlet is Danish, it transcends language and borders and even time, because it's as relevant now as it ever was. I think it [the neglect] has to do with the way Ireland sees Irish America.”

If you talk to Irish people who have left Ireland in-depth about what the experience is like, they'll tell you that emigration or to be abroad for a long time is an unsettling experience, Byrne says.

“But when you return there's not a great deal of curiosity about the life that you live outside the country. In other words, once you go you are in a way moving into some other world that doesn't really have a relevance to the people at home,” Byrne says.

“You get written out of the narrative. And because Ireland is a very insular country, and America is, too, in a different way, what people miss is the world of the local once they move away.”

There's not a great deal of interest about what's happening artistically in America in Ireland, Byrne says.

“Irish America isn't really something they think about. But there's a huge interest in what's happening over there here,” he says.

“We're interested in taking all the plays and poems and singers and writers over, but there's very little interest from the other side. I think a lot of Irish Americans feel that. That extends into the theater. Eugene O'Neill, what does he have to say to us?”

But what O'Neill is writing about in Long Day’s and other plays is the Irish emigrant identity, through his father from Kilkenny on down, Byrne says.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

“When O'Neill's father talks about what life was like as an immigrant he notes that his mother had to wash and scrub and he had to work at 10 years of age, at a time when Irish people were regarded as socially inferior. For someone who writes this perceptively about what it means to be an emigrant, it is curious there is no interest in him in Ireland,” Byrne offers.

That neglect is an immense shame because O'Neill's understanding of the Irish emigrant's experience is unparalleled. Onstage, his family wheel around like victims in the aftermath of an explosion, their hair at times still smoking from the blast. Given what they've lived through, it's no wonder that they've fallen into in a lifelong wrestling match that seeks to both wound and heal.

Some griefs are so profound that we cannot express them, yet we die to keep them, O'Neill reminds us. And some fears run so deep that we seem to spend our lives racing right toward them, not away from them, as we should.

There's something universal yet also particularly Irish about all this. It's something the Irish should pay more attention to, Byrne feels.

“The fear of the poorhouse that terrifies James in the play, I remember my own father using that word,” says Byrne.

“You don't want to end up in the poorhouse!” My mother's mother remembers her mother telling her about the Famine. It's that close to us in time. My mother inherited a notion of what hunger and starvation could do to a people, what it really meant.”

O'Neill's real-life father was haunted all his life by the notion that his luck could change and it could all be taken away.

“The relationship between Irish people and the land is there too when he says you can feel beneath your feet, banks you can't trust but land is land. There's a great deal of what it means to be Irish there. The remarkable thing about this is that it couldn't be more topical, it feels like it was written yesterday.”

* Originally published in May 2016. Updated in November 2022.

Comments