NYPD Commissioner James O’Neill leads the most famous police force in the world and couldn’t be prouder to do so. He talks to Debbie McGoldrick about his Irish background, keeping the city safe, President Trump and, of course, St. Patrick’s Day

THE NYPD commissioner’s office, on the top floor of 1 Police Plaza in downtown Manhattan, is impressive, to say the least. It boasts a picturesque view of downtown and is filled with all manner of police memorabilia. The commissioner has use of a desk that belonged to Teddy Roosevelt when he was board president of the New York City Police Commissioners from 1895-‘97 before he became president of the United States.

A plaque on one of the walls contains the names of the men who have served as commissioner since the position was created in 1901. The Irish, not surprisingly, are all over it, starting with Michael Cotter Murphy, the first commissioner, and others like McLaughlin, Mulrooney, Kennedy, Broderick, McGuire, Kelly and, since September of last year, James P. O’Neill.

It’s a position that O’Neill, always known as Jimmy, is immensely proud to have ascended to. The grandson of Irish immigrants first joined the force in 1983 as a transit cop and hasn’t regretted a single day since. He knows the NYPD literally from the underground up, inside and out, and is firm in his belief that New Yorkers are being protected by the finest men and women in the world.

“I consider myself a very lucky person,” O’Neill, 59, told the Irish Voice during an interview last week in his office. “My dad passed back in 1998 and I wish he was around to see this.”

O'Neill's grandparents were native of Longford on his mother’s side, and Monaghan on his father’s. The fourth of seven kids growing up in Brooklyn’s East Flatbush neighborhood, the O’Neill household was Irish in every way.

Read more: The tragic NYPD Irish cop who wrote one of Ireland’s best-known ballads

“We were. My father would listen to the Fordham radio station every weekend working outside, with the Irish music blasting,” O’Neill fondly recalled. “He would always listen to Irish music. I’m laughing thinking about it. He was such a good guy, but it was overkill at times with the Clancy Brothers! He liked Tommy Makem and the Dubliners too.

“I like the Dubliners more so than the Clancy Brothers. I like the old ballads. They are great.”

Joseph O’Neill was an executive for Drake’s Cakes which had a factory in Brooklyn but eventually moved to New Jersey. The commissioner speaks often of his mother Helen, 85 years young and in great health. She lives in New Jersey with one of her daughters and has watched her son’s career with a mixture of fear at first – she was afraid for Jimmy’s safety and said so – and for many years now, total pride.

“She’s the best. She had a knee replacement 10 or 15 years ago and it changed her life. It made her mobile again. She even drives a car,” O’Neill said.

His favorite photo in his office is of Helen on stage after her son was sworn in as commissioner last September 19, receiving a bouquet of flowers and a standing ovation from the VIPs in attendance, including Mayor Bill de Blasio and his wife Chirlane, Cardinal Timothy Dolan and all the top police brass.

Commissioner O’Neill’s mother Helen receives a standing ovation from city dignitaries on the day her son was sworn in. (Photo from NYPD)

“That would have been the first time in her life when she was in front of a group of 800 people and she was applauded. My sisters and brothers were down in the front too,” O’Neill remembers.

O’Neill doesn’t come from a family steeped in the policing tradition. His uncle-in-law Bill was a lieutenant in Brooklyn South who retired in 1973, and O’Neill cites him as probably the biggest influence he’s had in law enforcement.

“He always seemed to be happy. He had six kids and was always positive, always had a funny story and loved life and loved people. I really looked up to him,” O’Neill says.

Before joining the New York City Transit Police in 1983 – the force merged with the NYPD in 1995 -- O’Neill worked for an insurance company even though being a cop had always appealed to him more than any other career. His brief time in the business world proved less than inspiring, so he took the police exam thinking that if his time in uniform didn’t work out he could always leave.

That day never came and never will. But New York was a much different city back in the early 1980s. Petty and violent crime was rampant – to compare, 1983 saw 1,956 murders in the five boroughs; the number for 2016 was 330 – and riding the rails as O’Neill did as a rookie transit cop was especially dangerous given the run-down state of the subway system back then. No wonder his mother was fretful.

“As transit cops, we worked by ourselves. I worked from eight at night until four in the morning,” O’Neill recalled.

“The trains aren’t like what you see now. I rode the A train and the D train, three round trips a night. There was a rule that you could only stay in a car for three stops, and then you went to another car.

“It was an incredible experience. I was there to keep people safe and you could see walking from car to car, the relief on people’s faces when you walked into a car and they saw a cop. You could see the tension coming out of their body. They felt safe.”

O’Neill is friendly and engaging, so it’s easy to see why the direct contact he had with ordinary citizens made him love his time in transit. Ensuring that the NYPD is approachable and accessible has been a hallmark of his career and informs many of his biggest decisions.

“I liked the one on one and the opportunity to get to meet people,” O’Neill says. “I’ve always been – and my sister Sheila might disagree with this – maybe not an extroverted person, but someone who always likes talking to others. Maybe not to strangers, but when you are a cop you are not dealing with strangers because they know who you are.”

O’Neill steadily rose through the ranks of the NYPD, and while an officer he also earned a BA and a master’s in public administration from the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. He’s been commander of three precincts – Central Park, East Harlem, and the western Bronx – has led the vice, narcotics and fugitive enforcement divisions, and in December of 2014 attained the highest position a uniformed officer can rise to, chief of department, serving directly under his friend, Commissioner Bill Bratton. When Bratton resigned in August of 2016 for a job in the private sector, he strongly recommended O’Neill to Mayor de Blasio as the best candidate for the job of New York’s top cop.

Read more: Trump's deportation orders will not be followed says NYC top cop James O'Neill

The day starts at around 6:30 a.m., when O’Neill arrives in his office and works out for a while “to stay somewhat in shape,” he says. Many meetings follow – chief among them an intelligence briefing – and different groups throughout the city visit Police Plaza to talk about issues of concern. O’Neill spends large amounts of time speaking at various business events and community gatherings with one primary message in mind: to let everyone know that the men and women of the NYPD are on the job for the benefit of the people and to keep them safe.

“That’s my job, to make sure the narrative is correct,” he says.

But the relationship between the public and law enforcement has sometimes been a lightning rod for controversy, especially since the shooting of the unarmedAfrican-Americann teen Michael Brown by an officer in Ferguson, Missouri in August of 2014. The NYPD had its own unwelcome brush with national attention a month earlier after a patrol officer on Staten Island used a chokehold on an unarmed African American, Eric Garner, as he said that he couldn’t breathe. Garner died an hour later.

The grand jury verdicts not to indict the cops who killed Brown and Garner came within days of each other and prompted furious protests across the country, and a horrifying crime in New York: the December 20, 2014 execution of two NYPD officers, Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos, as they sat in a marked car in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn by a career criminal seeking revenge for Garner’s death.

“The last three years have been difficult,” O’Neill acknowledges. “It was especially difficult when Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos were assassinated. I think that was not a crushing blow for law enforcement, but if anything could come close that would be it.

“It was hard. It was hard for us to come back from that,” an emotional O’Neill adds. “But it speaks to how people feel about this police department. They have a sense of mission. We came back and we realized that no matter what happens people still call 911. They still call 311. They flag down cops. They still need our help.”

O’Neill is at the forefront of efforts to make neighborhood policing the gold standard in the five boroughs. The premise certainly seems logical: the more outreach officers have among the communities they serve, the more people will learn to trust and respect members of the force. For many years, since his days as commander of three precincts, particularly the 44th in the Bronx, O’Neill has believed that NYPD officers are willing and able to create positive relationships with the citizenry, provided they are given the chance and the tools to do so.

“What I saw [as commanding officer] made me the person I am today. The level of commitment by the cops and what a great job they do. Even back then, everybody said police officers have to get closer to the community, but if you look at the way that we did business, we really didn’t have an opportunity to do that,” O’Neill said.

“If you’re doing 20-25 radio runs and 911 runs in an eight hour period, there’s no chance to make a connection. And you might be working in a different sector every days. And then there’s other people in the precinct who would be doing anti-crime and quality of life enforcement and low level drug work…that model of policing, it was effective for fighting crime, but it wasn’t effective for community relations.”

In 2015, together with Carlos Gomez, now in O’Neill’s previous job as chief of department, and Terence Monahan, now chief of patrol – and with the blessing of Commissioner Bratton – O’Neill created a new policing model to re-sector many NYPD precincts to form natural neighborhoods, and to put the same cops in the same sectors every day. They also created a position called the neighborhood coordination officer (NCO) who serves as a conduit between the community and the sector cops.

Then NYPD Commissioner Bill Bratton, O’Neill and Mayor de Blasio at an August press conference where O’Neill was announced as the new commissioner. (Photo from NYC Mayor’s Office)

“The biggest thing to remember about neighborhood policing is that it’s a crime fighting model because that’s what we get paid to do, to keep people safe,” O’Neill says.

Under O’Neill’s model, officers spend about a third of their workday meeting people in their sectors, which allows them to go to things like community council and tenant association meetings and business gatherings. “It’s important to establish trust so that people can see not just the precinct commander and the two community affairs cops, but they can also see the people who are actually doing the police work,” the commissioner maintains.

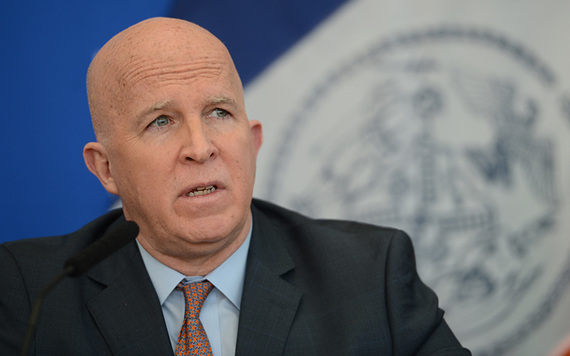

NYPD Commissioner James O'Neill.

“By and large we are getting positive feedback from the cops, anecdotally from the communities now served, and within the next couple of weeks we will be able to measure our effectiveness because there’s going to be a survey tool available through smart phones where you can give ratings to the NYPD.

“Do people feel safe? Are people being treated fairly? We will get real time feedback on all the important issues. Crime is way down, and I think we can still push it. The only way to do that is through neighborhood policing.”

President Donald Trump’s war on sanctuary cities and his demand that local cops act as de facto immigration agents has not gone down well under O’Neill’s NYPD. The commissioner issued a memo last month re-stating the city’s long-standing policy towards immigrants – effectively, that they are all entitled to the same police protection regardless of status – and he’s firm that nothing will change no matter what the White House says.

“No, no we are not,” O’Neill replied when asked if the NYPD would be implementing any new Trump orders targeted against immigrants. “If we are going to continue to keep people safe in this city we do that through building trust. Everybody, regardless if you are a citizen or regardless if you are undocumented, has to be able to trust the police. It’s the only way we are going to be able to keep people safe.

“Whether you are a victim or a witness or whether you are somebody we arrest, we still have to be able to communicate with you, and I think that is done through trust. We are at such a point now, the way crime is and the way we are pushing out neighborhood policing, we just don’t want to upset that balance. We really don’t. The cost is high. And this is not who we are.”

New York City suffered the worst terrorist attack ever on U.S. soil on September 11, 2001. The world hasn’t been the same since, but the shock, anger, and unbearable grief eventually gave way to a city that picked itself up and bounced back thanks to those New York values Senator Ted Cruz mocked during the GOP presidential primary campaign last year.

Counter-terrorism preparedness is a 24-7 operation within the NYPD. It’s true that New York is a safe city, but not for a minute can that be taken for granted given that we live in an open society, O’Neill cautions.

The NYPD has an ongoing relationship with its federal law enforcement partners in the FBI and the Joint Terrorism Task Force to ensure a free flow of information. “The relationships are important from an investigative perspective and help keep us safe,” O’Neill says. “Anything they know we know, and also the other way around.

“You know, we have a limited amount of resources. You think, 36,000 cops, that’s a small army, but this is a big city.”

New York's top cop James O'Neil.

Over the past couple of years, to better prepare for a rapid reaction to possible terrorist attacks or shootings, the NYPD established two new divisions: the Critical Response Command and the Strategic Response Group.

Ford Explorers marked with CRC on the side are assigned to areas throughout the city considered sensitive and high profile, while Strategic Response is an 800 person division that has a three-fold mission to respond to mobilizations, fight crime and respond to an active shooter or terrorist event. The NYPD’s Emergency Service Unit also continues to play a leading part, with its members constantly drilling and practicing to reinforce a seamless response if it’s ever needed.

“You just can’t relax,” O’Neill stresses. “Every day is new, every minute starts another part of the future, and you have to make sure you are paying attention to everything. I am blessed with the people I work with, the deputy commissioners and the bureau chiefs. They all have my time on the job, 34-35 years, and they are totally dedicated to what they do.”

Policing President Trump’s home, Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue in Midtown has presented several challenges to the NYPD, O’Neill acknowledges.

“Especially between the time he was elected and the time he was inaugurated,” he adds. The cost to the department for those few weeks alone came in at more than $25 million, and the NYPD is looking for financial assistance from the federal government.

“We needed a tremendous amount of resources. The Secret Service protects the president and his family, but we have to work with the Secret Service to make sure that not only is the building protected, but the area surrounding it is too. There’s a tremendous amount of vehicle traffic, a tremendous amount of pedestrian traffic, so it is a challenge for us,” O’Neill says.

The increased Trump-related activity on Fifth and 56th Street won’t present a problem for the biggest parade the city hosts each year: the St. Patrick’s Day march.

“No, that’s not going to be an issue at all,” says O’Neill, who is excited to march with the NYPD for the first time as commissioner.

“I’m really looking forward to it. It’s a great day out,” he adds. “It’s fun to meet a lot of the people on the avenue I’ve grown up in the department with, active and retired, so it’s good.”

This will be the first St. Patrick’s Day parade that O’Neill’s friend and hero, NYPD icon Detective Steven McDonald, won’t be a part of. McDonald, paralyzed in 1986 from the neck down by a teen’s bullet in Central Park, died in January after a heroic life dedicated to peace, faith, and forgiveness. O’Neill spoke eloquently at McDonald’s funeral Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and says the NYPD – and, indeed, the world – has lost a champion of everything that matters most in life.

The funeral of NYPD icon Detective Steven McDonald.

“Steven struggled with every single breath, and he continued to be such a positive influence not just on the NYPD or the city, but the world. That is not an overstatement,” O’Neill said.

He speaks highly of McDonald’s widow Patti Ann and only son Conor, a member of the NYPD who was promoted to sergeant last September. “Steven has a terrific family. Conor is working for Chief [Terence] Monahan now, the chief of patrol, and he’s got a bright future,” O’Neill says.

The big Irish question looms: has the commissioner ever traveled to Ireland?

“I knew you would ask me that and I’m a little embarrassed to say that I haven’t,” he says. “Everyone else in my family has. One day.”

That day, though, won’t be in the near future. Being commissioner of one of the largest police forces in the world is all-consuming. But O’Neill wouldn’t have it any other way.

Ireland’s Taoiseach Enda Kenny, Commissioner O’Neill and Ireland’s Ambassador to the U.S. Anne Anderson at the Irish Consulate in New York last December. (Photo by James Higgins)

“For me, with this job, every day is a good day. How many people get an opportunity like this? I’m the 43rd commissioner, so while I am here I have to do my best to ensure that I keep the city safe,” he says.

The father of two grown sons does make some time for a couple of passions: bike riding and playing ice hockey. “Yes, I definitely have to find a little time to keep in shape, or else you get run down,” he says.

A particularly memorable time on his bike came four years ago, when O’Neill took part in a four-day charity bike ride from Washington, D.C. to New York with members of the Garda, Ireland’s police force. He laughs at the memory.

“It was hilarious. We had the best time. There were about 50 people from the Garda. I thought I was a fairly decent cyclist but they taught us how to ride! They were a little older than us and they were amazing,” he recalls.

“Cops throughout the world have a kinship. I talk about that all the time, why police officers are so close no matter where they come from. We have that shared experience.”

As it turns out, O’Neill made the right choice giving up his old insurance job. Even his beloved mother Helen is on board now, after years of worrying for her son’s well-being.

“It’s been incredible. Being a part of the NYPD, you get the opportunity to make a difference in people’s lives,” O’Neill says.

“That’s the discussion I had with my mom. She said that’s not true, and I said it is true, even if it’s just one person at a time. She is the most kind-hearted person I know, but she just didn’t want me doing this. But yes, she’s good now and happy that I did.”

Comments