Earlier this month, the literary gods that decide these things sent me a message from the great beyond and said it was high time I finally read, front cover to back cover, Pietro di Donato’s 1939 novel Christ in Concrete. (What, you think we only read Irish stuff around here?)

This raw New York story is about an Italian immigrant laborer working under such unsafe conditions that he is literally drowned in concrete, following a building collapse.

If this sounds a bit heavy on the symbolism and, thus, a tad unrealistic, that’s understandable. But it’s actually happened to di Donato’s own father, who (like the victim in the story) was an immigrant named Geremio. It’s also what happened exactly 60 years later, in Brooklyn, to a 21-year-old Mexican immigrant named Eduardo Gutierrez.

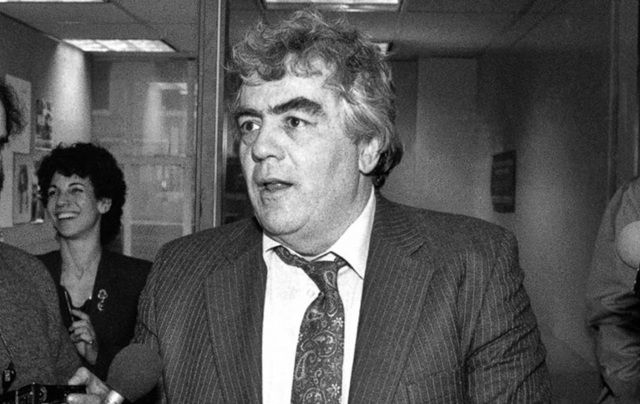

Like di Donato before him, legendary New York newspaperman Jimmy Breslin, who died earlier this month at the age of 88, transformed this horror into literature, in his epic, unsettling 2002 book The Short Sweet Dream of Eduardo Gutierrez.

When Breslin died, there were so many things to remember about him. His humble Queens upbringing. His decision to interview John F. Kennedy’s grave-digger following the president’s assassination. His correspondence with “Son of Sam” killer David Berkowitz. His hard-hitting columns on corruption in New York City that won him a Pulitzer.

There were so many famous Breslin stories to recount that some simply got left out.

One such story is that of Gutierrez, which would have been little more than a few small headlines in the newspapers if Breslin had not suck his teeth into his story and transformed it into a cautionary tale of the glory and horror of the American immigrant experience.

Breslin explored the shoddy construction practices that spurred the Brooklyn boom that shows no signs of stopping, that lined many pockets, and that led to Gutierrez’s death.

Breslin traveled to the central Mexican town of San Matias Cuatchatyotla, where Gutierrez was born to a 15-year-old mother, and a father who was -- sadly but fittingly -- a brick seller. These immigrants, Breslin notes, “come north with a faith that seems as deep and strict as that of the Irish.”

Finally, Breslin shone a bright light on the dark underbelly of the Rudy Giuliani years in New York, making The Short Sweet Dream of Eduardo Gutierrez one of those Dickensian books that help you understand the vast forces that make a city actually function.

Jimmy Breslin.

At one point in the book, Breslin writes of the streams of immigrants who once came to America “from Magilligan in Northern Ireland, from Cobh in southern Ireland, from Liverpool and Naples and Palermo and Odessa.”

So imagine one of those ships, from Cobh, say. And it arrives in New York, say, in 1900, and among its passengers is an Irish immigrant named Morrison who settles in Manhattan, before his son moves out to Queens, and his grandson, by the late 1960s, ends up fighting a war in a place called Vietnam.

That could very well be the back story for another criminally underappreciated Breslin work, the novel Table Money.

By 1970, Vietnam vet Owney Morrison is back in Queens with his wife, a Congressional Medal of Honor, and job alongside his father working as a “sandhog.”

So much of this turf has been covered by others, and been slathered in stereotypes and sentiment. And while Table Money may not be a perfect book, it is easily among the best explorations of the small towns that ring the great cities of the world. These neighborhoods are populated by deeply unromantic people who just happen to make the country go.

Table Money is both excruciatingly tough and unexpectedly tender. Like its author, it can seem crass and cranky. It, too, helps you understand how a city -- how the world -- works.

A vast cemetery abuts the Morrison home in Table Money. Breslin has joined these Queens dead.

But with Table Money, with The Short Sweet Dream of Eduardo Gutierrez, with all those wonderful columns, Breslin long ago joined the ranks of the immortal.

Read more: Jimmy Breslin passes -- the prince of New York City

Comments