“Martin McGuinness was NOT a terrorist. Martin McGuinness was a freedom fighter." Gerry Adams, his voice shaking with anger and emotion, defiantly insisted on the difference in his oration at the graveside of McGuinness in Derry last week as the former IRA leader and deputy first minister was laid to rest.

Adams' anger no doubt was prompted by media coverage which had referred to McGuinness as a "former terrorist." The timing of last week's terrorist attack in London was unfortunate for Sinn Fein. It happened the day before the McGuinness funeral, making the comparison inevitable.

The death of McGuinness naturally led to assessments of his entire career, not just the later part when he was in non-violent, political mode. The earlier part of that career was replayed in detail on TV and in newspapers last week in all its gruesome horror.

With pictures of the aftermath of IRA bombings in Britain and the carnage of the wider IRA campaign over the years, with all its innocent victims, how could the attack on Westminster be called terrorism, but not what McGuinness had directed?

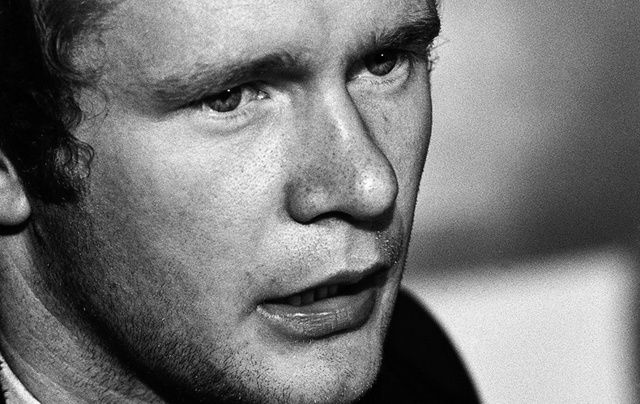

McGuinness in the military garb of the IRA.

Most of the media last week acknowledged McGuinness' key contribution to the achievement of peace in Northern Ireland, but still the "former terrorist" label was applied to him frequently. Which is what led to Adams’ angry rebuttal in the graveside oration: “Martin McGuinness was NOT a terrorist. Martin McGuinness was a freedom fighter."

So where is the truth? The realpolitik determination in political circles to "move on" from the past and make the peace settlement in the North work has meant that for some time now McGuinness' Chuckle Brother persona has become the dominant image of him. But this glosses over the appalling things that were done to so many innocent people under his leadership of the IRA.

Part of this effort by the British and Irish governments to keep the peace settlement in place has meant avoiding terms like terrorist or terrorism whenever the IRA is mentioned. That has implied a degree of acceptance of the Sinn Fein/IRA narrative of a "struggle" waged by "freedom fighters.”

Calling either Adams or McGuinness "former terrorists" is not seen as helpful. But is it accurate?

The usual definition of terrorism is the use of indiscriminate violence against ordinary people to instill fear and thereby force through a political aim. By any yardstick, that is what much of the IRA campaign in Britain -- when either Adams or McGuinness were on the IRA Army Council -- was doing. And on that basis it is accurate to label McGuinness a former terrorist (and Adams as well).

The massive car bombs in London, the pub blasts in Guildford and Birmingham, the litter bin bombs in a shopping street in Warrington that killed two boys -- these can only be categorized as terrorism, since the targets were civilian, not military.

Giving warnings by phone, which were frequently inadequate or inaccurate, did not change this. The IRA were gambling -- and frequently losing -- with ordinary people's lives, creating terror with the aim of pressurizing the British government.

Of course the campaign in Britain was only part of the terror story. Equally horrific acts were carried out by the IRA in the North -- the knee cappings, punishment beatings and murders that were done to keep their own side in line. And the execution of so many ordinary people on the loyalist side -- postmen, farmers in isolated areas on the border, etc. -- to instill fear and destabilize society.

It's hard to describe this in any way other than terrorism. On McGuinness' watch, the IRA were not just killing policemen or soldiers. They were killing ordinary people going about their everyday lives. The IRA killed hundreds of civilians rather than members of the security forces.

One incident that most people remember with revulsion was the La Mon hotel bombing on a night in February, 1978. The hotel near Belfast was packed with people at a dinner dance when the IRA set off a hidden bomb attached to cans of petrol, killing 12 and leaving many more with very severe burns. The IRA later said they had tried to give an early warning but the public phone nearby had been vandalized.

Any link with the British no matter how remote was seen as justification for grotesque acts. There are many examples, but let us remember one, Patrick Gillespie, a Catholic man who worked in the kitchen at an army base in Derry at a time when jobs were scarce.

While his wife and kids were being held hostage, he was forced to become a "proxy bomber," driving a van laden with explosives up to an army checkpoint. As he arrived the bomb was detonated remotely by the IRA who were following behind, killing him and five soldiers. This operation in 1990, one of several "proxy bombs,” was run by the IRA in Derry, which was controlled by McGuinness.

One could go on and on with this, with examples of what can only be called terrorism carried out under the direction of McGuinness. One poignant one that sticks in the mind was the cold blooded murder in 1981 of Joanne Mathers, a young mother who was collecting census forms in a housing estate in Derry. As she stood on the doorstep of one house she was shot in the neck by an IRA gunman who grabbed the forms from her hands -- the IRA opposed the census.

Again, this was done on McGuinness' turf and while he was in charge. And over the three decades that the IRA fought their campaign there were many such terrorist murders, some of them in the south.

An old photo of Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness.

The high profile example that everyone remembers was the killing of Mountbatten, the Queen's cousin, when his small fishing boat was blown up off the Sligo coast in 1979 by an IRA bomb detonated remotely from a nearby cliff. This action, authorized by McGuinness, made world headlines. Less remembered is that three other people on board also died in the blast, one of them a 15-year-old boy who was working on the boat.

Whether incidents of this kind mean that the IRA were terrorists is at least open to debate. The evidence is compelling in many of their actions. But apart from that, it is doubtful whether the term "freedom fighter,” as used by Adams last week, is in any way appropriate.

No matter how bad the unionist regime was in the 1960s -- and it stank -- what was at stake was equality, voting rights, job opportunities, access to housing, etc. for the Catholic/Nationalist people in the North. It was particularly bad in Derry, where McGuinness grew up.

But oppressive though it was, no one was being banned from bathrooms or being lynched. The comparisons with blacks in the southern states in the U.S. or the apartheid regime in South Africa are overblown.

It is arguable that the civil rights campaign in the North, despite the violence of the loyalist mobs, could have led to a satisfactory outcome within a few years. Certainly the British government was waking up to the reform that was needed. And it is worth remembering that the British Army, which had been deployed initially to the North to protect Catholics and was welcomed by them, could have played a decisive role in that.

Instead the IRA started to shoot at the troops, mainly because they could see that this scenario threatened their goal of a united Ireland.

What was needed was a power-sharing settlement to bring equality in the North, which was offered in the Sunningdale Agreement in 1974, more than 20 years before the Good Friday Agreement did much the same and Sinn Fein/IRA decided it was acceptable.

Sunningdale was undermined by the other Chuckle Brother Ian Paisley and his mobs, but the IRA also continued its campaign of violence at the time. By then the IRA aim was no longer just to "defend Catholic areas" but to force a complete British withdrawal from the North.

This was never going to be achievable because of the unionist presence -- and it is worth remembering that the

loyalist population have been in the North as long as the pilgrims in the U.S. Driving a million of them back to Britain or forcing them into a united Ireland 300 years later was never a realistic option.

The real heroes from that miserable time were those who took the more difficult non-violent path, people like John Hume, Seamus Mallon and so on. It's easy now to forget that the vast majority of people north and south (including the majority of Catholics/nationalists in the North) did not support the IRA campaign. So whether you can call McGuinness or the IRA "freedom fighters" when they were not supported by the majority of people in Ireland is doubtful.

Over the years the IRA campaign descended into what one writer last week called "nihilistic barbarism." Eventually, two decades too late, the realization dawned on McGuinness and Adams that their "war" was unwinnable, not least because the IRA by then was riddled with informers and the situation had reached stalemate. So they switched to non-violence and politics.

This was a pragmatic decision rather than a moral conversion, something that is clear from the absolute refusal of McGuinness or the rest of the IRA to ever admit that their actions were wrong and to apologize.

On the contrary, McGuinness liked to turn up at welcome home parties for the worst IRA killers when they were released from jail, as he did when the Mountbatten bomber was released in 1998.

The late conversion of McGuinness to non-violence and the political path was welcome when it came. And to be fair to him, once the decision was made he worked tirelessly to make the peace agreement work. He deserves credit for that.

However, the virtual canonization we saw last week at his funeral -- with Bill Clinton doing his folksy thing -- was badly misguided. It was an exercise in reshaping a bloody history that has left so many innocent victims in its wake, with so many families still grieving and suffering.

The horrible disease that took Martin McGuinness so quickly no doubt intensified the emotion and the misplaced nostalgia on the day for the lost Chuckle Brother. But we should all remember that he was Saint Martin de Provos, not Saint Martin de Porres.

Read more: Why Martin McGuinness will be remembered for hundreds of years to come

Comments