It seems unlikely enough this week that the Ulster politicians of about every ancient hue will be able to cobble together a power-sharing administration that will prevent the imposition of direct rule from London again.

That is the way it looks, but then it is also a fact that the savage election campaign which created the current scenario was one in which a surprising number of the old moulds of six county realities were shattered. I never thought I would live to see the day in which Sinn Fein would emerge with just one seat less than the unionists. The times surely are a-changing.

The backdrop to the ongoing talks is complex and fascinating too. Brexit and its many social, economic and political implications for both the North and the Republic was probably one of the spurs which drove out the electorate in such numbers on voting day.

Will a manned border with customs and security checks return? Will the Good Friday Agreement which brought relative peace to the North for the past decade be protected by Brussels? Will immigrants wishing to enter England post-Brexit try to use an Ireland with a so-called "soft" border to get in by the back door? There are many questions and many problems to be solved in the next three weeks.

As a Fermanagh-born nationalist Catholic who has been fortunate enough not to have had to emigrate from the North like so many of my peers, there is one life reality for the Ulster population which the politicians should take aboard during their current crucial talks.

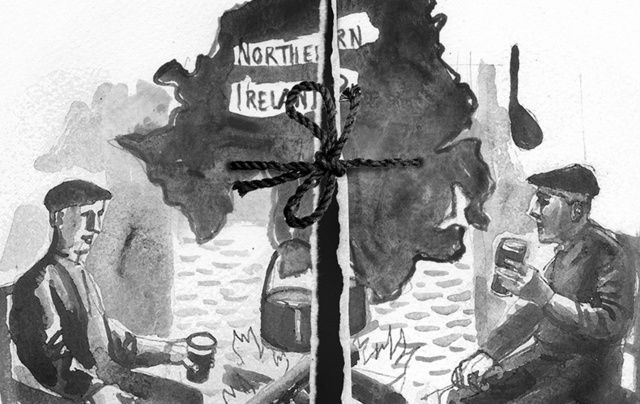

After more than a half-century residing in the Republic I can say with total conviction that Ulstermen and women, whether orange or green or neither, have infinitely more in common with each other than with any other grouping in the British Isles. That is a fact which I did not realize for years.

The hard history which has spilt so much blood down the centuries and created such division and strife and hurt has also, paradoxically, forged a fundamental subliminal bond between orange and green. We understand the hidden depths of each other in a way that the Corkman or the Londoner never can and never will. Underneath the skin, too, there is a mutated kind of respect for the views and values and attitudes of the other side.

As a wee Northern man in the Republic all my adult life, it is a strange truth that I have always been treated that tiny bit differently by the communities amongst whom I have lived. There are some, for example, who hear my accent and not so subtly begin to try and ascertain if I am an Orangeman. Or what is my connection with the IRA?

The decades of The Troubles created a situation where many in the south would prefer to spend their evening away from the sound of that sharpish northern accent so often associated with civil strife and horror. I can understand that too.

Another rarely defined reality in the North is the fact that, apart from the traditional urban interface zones and defensive walls, the folk of orange and green in the rest of the province have always contrived to span the historic divide between them with countless bridges of neighborly and community respect, understanding and compassion where necessary.

I can illustrate that with the truth that my shopkeeper father's best friend was the Protestant and orange farmer who lived next door. They had to be subtle in their relationship.

Bob could not be seen spending his orange money in our green shop for example. He would routinely come down to our house after darkness fell, drink a bottle of stout by the fireside with Sandy, and one of us would collect his shopping for him. He was a B Special as well but that did not prevent us looking after his farmwork for him every Twelfth of July when he donned his sash and went off to march in the footsteps of King William of the Boyne.

If you had a family emergency of any kind, from a chimney fire upwards, you could be certain that your Protestant neighbor would be the first to arrive with help. That always was and is another truth in the province.

There was also, in my view anyway, a poignant regret in that community that, because of our history, they were isolated culturally from so much of the Irish identity tags like the music, the language, the Gaelic games and suchlike. That situation has been blunted in recent decades but, ironically, the perceived slighting of the Irish language by the last administration was one of the lesser triggers which led to the downfall and the current tricky situation.

The unionist, descended from the first hardy Planters, in many ways had to behave as they have behaved down the centuries because of their situation in our history. We began to kill them, frequently from ambush, from when they came into the province to steal away our land.

They had to cruelly discriminate against the green community because, given that the Catholic church forbade contraception, that green community, totally priest ridden at the time, would outbreed them in a couple of generations and vote the province into a united Ireland. So they had to deny us jobs and homes in our own province and get generations like mine out of there as quickly as possible.

Because the minority populations across the province had bigger families to support and usually less fertile farmlands the majority folk, with smaller families -- typically two -- and more fertile farms, and better job opportunities all round, were always more prosperous.

It is also a fact, even today, that the descendants of the Planters, with thrifty and industrious Scottish blood in their veins in many cases, are the most successful farmers, for example, in all of Ireland. I researched a story years ago about the blood types common in Ireland and discovered that even the most common blood groups are markedly different in Ulster to the rest of the island, again an aspect of the Plantation.

We minority folk, when I was growing up in Fermanagh, always referred to the Republic as the Free State. Our unionist neighbors never used the word free...they called it the State. And our Free State, in those decades, was palpably poorer and less developed than the North with its strong welfare services supported by the British government.

Anyway, in a nutshell, as the tricky talks begin with Sinn Fein now virtually as strong as the unionists in terms of seats in a new Assembly, my main point is that all the people of the North, whatever their surface differences, have infinitely more in common with each other than they have with anybody else. And one hopes that unity will somehow surface in the end.

Comments