Ireland’s disproportionate influence within the EU can be a valuable asset for the Trump Administration

Ireland, despite its small size, is a valuable partner for the United States of America, and one that was neglected under the Obama Administration. There is a new opportunity with President Trump.

With the impending departure of the United Kingdom, Ireland will be the only English-speaking, common law member of the European Union (EU) and, therefore, should be America’s natural gateway to Europe.

Ireland has a disproportionate influence within the EU. That influence can be a valuable asset for the Trump Administration if the relationship is carefully cultivated.

Donald Trump at his golf resort in County Clare, Doonbeg.

As Europe is generally culturally hostile to American interests and particularly this administration, it will take many years to change these attitudes. It would be both achievable and desirable for the United States to turn Ireland into a firm friend in the medium term.

With a newly revitalized US-Ireland relationship the Trump Administration would be on a firmer footing as it manages the transition away from the Obama/Clinton ‘pivot’ to Asia and back towards a more balanced approach.

However, in the short term the impending departure of the United Kingdom (UK) from the EU will bring some difficult negotiations related to the border with Northern Ireland and how this pertains to the Good Friday Agreement. So it is highly likely that it will be American influence on Europe and the UK that the Irish will be looking to lean on for support.

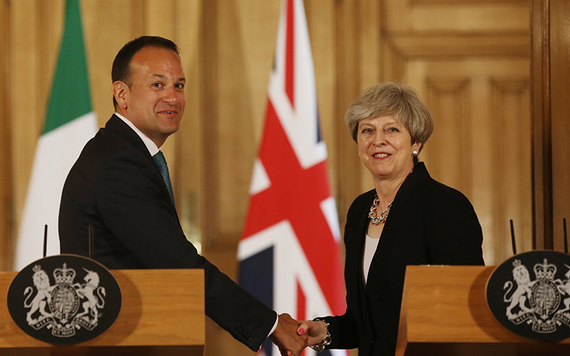

Ireland's leader Leo Varadkar and British Prime Minister Theresa May.

Historically, the American-Irish relationship has suffered from a ‘misty-eyed’ view of the ‘old Country’ held by many Irish Americans, an associated misunderstanding of the historical conflict in the North and deep ties with the Democratic Party.

As a result, Americans too often focus on Ireland’s cultural aspects, great as they are, to the exclusion of her economic assets. Furthermore, the GOP and its pro-growth economic policies have not had as a receptive an audience as they have had in other countries such as the UK.

The Ireland of today, however, is a very different country from the one imagined by many Irish Americans; it is multi-cultural, multi-ethnic and multi-denominational with less than 30% population being weekly Mass-goers.

Grafton St, Dublin: Modern Ireland is not what many Irish American's think it is.

In 2017 Ireland appointed a gay Prime Minister of Indian ethnicity. Ireland is an open, economically agile country largely as a result of the tax reforms of the 1990s and 2000s which sparked an economic boom that catapulted Ireland from the ranks of Europe’s poorest countries to among the continent’s richest.

At the same time, the reforms, especially Ireland’s aggressive lowering of its corporate tax rate, spurred imitators across Europe and even further afield. Not everyone in Brussels has been happy with this sort of tax 'competition,’ but it has been a major pro-growth force in Ireland and abroad. Indeed, the Trump administration has proposed its own version of corporate tax reform to spur US growth.

Aside from lowering of the US corporate tax rate the Trump administration is focused on the repatriation of the overseas earnings of American companies. Any move which makes it a lot easier to bring home foreign earnings for US companies has the potential to cause long term damage to the Irish economy, particularly in areas such as software and pharma.

While Foreign Direct Investment from the US has been a great boon to Ireland, stifling regulation and top marginal tax rates on personal income that exceed 50% and kick in below $50k have largely prevented a domestic entrepreneurial boom to match its economic expansion.

Just as the US can learn from Irish tax-policy innovations – both its successes and shortcomings – Ireland can look to the US for lessons on new-business formation and cultivating home-grown innovation.

A map of just some of the US companies based in Dublin's Silicon Docks.

The human and intellectual capital that Ireland has accrued gives her the potential for a new economic breakout, but it will need a new wave of reform to realize this potential. This presents a natural opportunity for collaboration between these two old friends.

A new wave of economic growth in Ireland, built in part on the foundation of decades of American investment in the country, would be a win for both sides. However, for the Irish Government not to act, not to be bold, not to push through tax and regulatory reform, to sit back and hope that things will just work themselves out would expose the country to grave economic risks particularly when one considers what the logical action by US corporates would be should the proposed Trump tax reforms become law.

While ‘Brexit relocation’ may buffer the Irish economy to some degree, domestic-led growth is what is really required for an Irish economic breakout to offset any decline caused by US dollar repatriation.

Investment from the US has in large part been responsible for the growth of a significant base of intellectual capital in Ireland over the last 25+ years. Not to capitalize on this and Ireland’s revitalization would be a tremendous wasted opportunity, particularly when one considers the well of goodwill for the US that already exists in the country.

The US needs an updated policy towards Ireland, with representatives more focused on economics than culture, looking forward to the future rather than backward into the past.

In 1998 Bertie Ahern unleashed the Celtic Tiger with his first brave steps towards lowering the corporate tax rate; Taoiseach Varadkar would do well to show similar bravery, to ignore the critics both in and out of his own party, to 'grasp the nettle' with both hands and to address the issue of a personal tax regime which stifles growth and discourages entrepreneurism. It’s a time for change. Go for it Leo.

* Michael George is a partner in the Versant Group.

Comments