As the Trump administration seeks to abolish the role of US special envoy to Northern Ireland, the Irish Echo looks back at the success of those who held the position in achieving and maintaining peace in Northern Ireland.

Back in August 2009, all was quiet at Stormont.

Well, relatively quiet.

Summer holidays doubtless helped.

The Executive and Assembly were up and running after Sinn Féin had ended a boycott of the former the previous year.

Things were moving along to the extent that U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton reckoned that they could move on their own without Washington’s prompting, and presence, in the form of an envoy.

She would, of course, be keeping an eagle eye on things from the State Department, or whatever country she might find herself in as Washington’s chief diplomat.

“I and my team are on call to help in any way we can as the continuing decisions have to be made to realize the full benefits of a Northern Ireland at peace and moving toward the kind of prosperity they’re looking for,” Clinton told the BBC.

She was in Thailand when she said this.

Read more: Shock as Trump administration to eliminate Irish special envoy position

As Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton first suggested that Northern Ireland no longer needed a full-time special envoy

As the Echo reported at the time, pressed as to whether a part-time envoy might be employed, Secretary Clinton responded: “Well, it’s part of the responsibilities that we’re taking on that, just like I supervise the special envoy for the Middle East and for Afghanistan and Pakistan, and climate change and everything else, as well as running the dialogues with India, Russia, China, and so much, this is one that we’re going to really keep a close eye on.

“I’ve been in consultations with representatives of the Irish government, the British government, the Northern Ireland leadership, and we’re going to be as helpful as we can.”

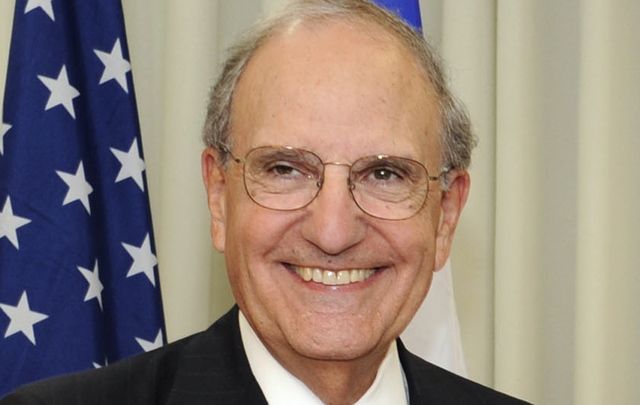

Acknowledging the work of the first U.S. special envoy, George Mitchell, Clinton said that all the parties involved with Northern Ireland had achieved a great deal of what was envisioned back in the 1990s and, as a result, there was no necessity for a singularly dedicated, full-time U.S. official to oversee the situation.

“The problems that the continuing efforts toward finalizing the agreements in the Good Friday accord are really up to the parties themselves, and certainly in consultation with the British government and, to a lesser extent, the Irish government,” she said.

“So I don’t see the need for someone full-time. But obviously, I’ve spent many years in this, on this issue. I care deeply about the outcome. I know the players. I stayed closely in touch with them when I was in the Senate, so I’ve made it clear that I and my team are on call to help in any way we can as the continuing decisions have to be made to realize the full benefits of a Northern Ireland at peace, and moving toward the kind of prosperity they’re looking for.”

Clinton, for sure, still cares, still keeps an eye on the North and its affairs – but as a private citizen residing in Chappaqua, New York.

And while right now there is no U.S. envoy, and unlikely to be one given the recent moves undertaken by current Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, things have not been moving along so swimmingly up on Stormont Hill.

And even if they were, many Irish Americans are of the view that the United States has a legacy to protect in the Good Friday Agreement, the grand deal that gave birth to the Assembly and Executive.

Read more: Iconic priest of The Troubles praises Hillary Clinton’s role in Irish peace

Secretary Clinton appointed a U.S. envoy to the North who was confined to economic and business-related matters

As it happened, Secretary Clinton did preside over the appointment of a U.S. envoy to the North, Irish-born Declan Kelly.

Kelly’s brief, however, was confined to economic and business-related matters. He would have no overt political role.

This was not the case for his envoy predecessors, three of them, who found themselves up to their eyes in the tangled weave that is Northern Ireland politics.

The aforementioned Senator George Mitchell, President Bill Clinton’s special envoy, had blazed the trail.

There was some concern that when Vice President Al Gore, who had promised to continue the envoy role, lost the 2000 election to George W. Bush that the U.S. would take a step back from Northern Ireland.

Despite concerns, the Bush administration with valuable foreign policy experience

Dr. Richard Haass.

That would not be the case. Indeed, the Bush administration would appoint a man with considerable expertise in the foreign policy field, Dr. Richard Haass, and do so promptly.

Haass, head of the State Department’s policy and planning office, was even given ambassadorial rank by the U.S. Senate and promptly went about his business cramming ten meetings with British, Irish, and Northern Irish representatives while on a short visit to London – this as the Bush administration was still measuring the drapes at the White House.

Not that all was just a mirror image of the Clinton administration’s ministrations in the North.

The White House would not refer to Haass as an envoy or special envoy.

He was America’s “special point person.”

Outside 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue everyone called Haass an envoy.

Whatever he was called, Haass performed well at his task at a time when there was considerable agitation between the parties and leading political figures at Stormont.

The era of envoy Dr. Mitchell Reiss who withdrew visa privileges for Gerry Adams

Mitchell Reiss.

At the end of 2003, Haass was succeeded as point person/envoy by Dr. Mitchell Reiss. Haass was to return to the north a decade later to chair, along with Dr. Meghan O’Sullivan, inter-party talks aimed at addressing some of the unresolved issues from the peace process such as parades, flags and "the past,” issues that could have kept Haass busy every day of his ten-year absence from the North’s affairs.

Mitchell Reiss well summed up the fact that for most of its years of independence the United States had not treated Ireland as a standalone foreign policy issue, one outside the long shadow cast by Great Britain.

As with Richard Haass, Reiss had directed policy and planning at the State Department. Like Haass, he was accorded the rank of ambassador when he set off for Northern Ireland.

The North part matched the Mitchell Reiss skill set. But his north, the focus of his academic endeavors, was North Korea.

Still, one tricky place was the groundwork for another.

Reiss was not shy about taking things on. At one point he withdrew visa privileges for Gerry Adams at a point in time when Adams and his party were at odds with their unionist partners on matters dealing with justice and policing.

He would utter strong words in the direction of unionists when, at one moment in his four-year tenure, loyalists made an unholy show of themselves in street marches.

Being the representative of the world’s greatest superpower didn’t protect Reiss from a unionist tongue-lashing in return.

But that spurred positive words from Irish Americans who enjoyed the sight of an American diplomat sticking the boot in.

Much of Reiss’s time on the job would be taken up with academic commitments at William and Mary College in Virginia. But no matter where he was, he was Washington’s man in the North.

“I would have the greatest confidence in Ambassador Reiss,” Fr. Sean McManus of the Irish National Caucus said after a Reiss briefing of Irish-American community leaders in Washington.

“While I might disagree with him on individual, specific issues, I think he can still do an excellent job and will.”

The only female envoy, experienced diplomat Paula Dobriansky

Paula Dobriansky.

Reiss continued in the job until 2007 and for the final couple of years of the Bush presidency, the envoy position was filled by another experienced diplomat, Paula Dobriansky.

Like Reiss, Dobriansky arrived in the envoy post with a mind relatively uncluttered by thoughts of Northern Ireland, her area of particular expertise is Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.

East Belfast, then, was a whole new ballgame.

But Dobriansky persevered and took her place in the pantheon as envoy/point person number four.

For sure, Irish America was getting used to the idea of an envoy, first promised by candidate Bill Clinton (and also Jerry Brown) at an Irish American Presidential Forum in New York in the opening days of April 1992.

Being used to the idea meant discussing it. Discussing it meant floating names.

While the White House and State Department had its own ideas as to the type of person who would make a perfect plenipotentiary, Irish America also had its favorites.

A list that emerged from one community gathering in the summer of 2005 was nothing if not eclectic. It included Ambassador Howard Baker, Tom Brokaw, Mario Cuomo, Bob Dole, Bill Flynn, Lee Iacocca, former Oklahoma Governor Frank Keating, former senator Sam Nunn, George Pataki, Colin Powell, General Norman Schwarzkopf, and former General Electric head, Jack Welch.

All men as it happened. Perhaps Paula Dobriansky was a deserved riposte.

Clinton continued to keep her eye on Northern Ireland as Secretary of State

Clinton claims to have kept an eye on Northern Ireland when she was Secretary of State.

When Barack Obama was elected president the expectation was that the envoy post would be maintained.

But more than Obama it was Hillary Clinton who had the street cred when it came to Northern Ireland.

With Clinton in the State Department, Declan Kelly would serve as Economic Envoy from September 2009 until May 2011.

Following his departure, there was something of a hiatus, though always a sense that Hillary Clinton was keeping an eye on things from, well, Thailand and other far-flung parts.

Clinton departed State in 2013, however, and once again Irish American brows became furrowed.

Her successor, John Kerry, poured balm and with his appointment of former senator and presidential candidate Gary Hart as his personal representative, Kerry effectively restored the envoy position, though Hart’s portfolio was often described in more nuanced terms as being an observer to the peace process.

Observe he did, sometimes from right up close and, like his predecessors, Hart would occasionally brief Irish American community leaders on the state of play in Belfast from the State Department’s perspective.

Hart would take his leave with the change in administration in January of this year, but came back into view in more recent days when he condemned the plan by Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to abolish the North envoy job as “a sad, even tragic, decision.”

Hart said the scrubbing of the envoy role came at a critical time in Northern Ireland when it had no devolved government and there was uncertainty over Brexit.

“This is a secretary of state who seems to be making it up as he goes along,” Hart told The Irish Times.

“There is unreconstructed devolved government in Belfast, and Brexit is a critical, critical issue and there ought to be some person on the case who knows Ireland, who understands the issues and who can get along with the two governments, but we don’t have that person,” he said.

“If they look at the UK generally and Brexit, all they see is complications and they run away. I don’t think they want to be engaged and if you get complexities like the border issue, the last thing that Tillerson wants to worry about is the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic. It is not on his radar.”

The post may now come to an end under Secretary of State Rex Tillerson

Will Secretary of State Rex Tillerson permanently abolish the special envoy role?

What was, and is, on Secretary Tillerson’s radar is not just the North envoy job but an array of envoy positions dealing with countries, regions, and issues around the globe.

Specifically, with regard to Northern Ireland, Tillerson proposed in a letter to Senator Bob Corker, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, that the role of “Personal Representative for Northern Ireland Issues” be “retired”.

If nothing else, the envoy posting went out with a longer job title.

Tillerson wrote Tennessee’s Corker that “the 1998 Good Friday Agreement has been implemented with a devolved national assembly in Belfast now in place.”

As the Irish Times noted, no reference was made to the collapse of the power-sharing assembly.

“Legacy and future responsibilities” for Northern Ireland would be assigned to the State Department’s Bureau of European and Eurasian affairs and the budget of $50,000 (€42,000) supporting the Northern Ireland envoy role would be realigned within that bureau.

This stated figure would be something of an eye-popper.

Irish America credits the U.S. intervention in Northern Ireland as being the game changer that led to an end of the Troubles and the emergence of devolved, power-sharing government.

If nothing else, Irish America, and many others besides, got a very big bang for not very many bucks.

And now there is just silence from Washington.

To subscribe to the Irish Echo e-paper, click here.

Comments