We have seen the enduring courage, love, devotion and determination of family members bear fruit in two cases known for decades as monuments of injustice: the Birmingham Six and Bloody Sunday.

What is it that sustains family members of murder victims to pursue truth and justice for their loved ones over the course of decades? Where do they find the courage necessary to overcome obstacles, official and otherwise, placed in their way?

Strength comes from the heart: love for those who were lost and devotion to their memory. Additional motivation comes from being subjected to the indifference of and falsehoods from others, about how and why their loved ones were killed.

When official accounts are lies, they must be challenged. Uncovering the truth in this situation takes unwavering determination. Setting the record straight means one will not allow the victim’s life to be devalued. It means one will not allow the victim’s death to be treated as meaningless.

At a fundamental level, setting the record straight expresses society’s acknowledgment of a devastating loss. It makes it possible to hold wrongdoers accountable. Without some expression of societal acknowledgment and accountability, a survivor cannot achieve closure or begin to heal.

Read more: Bloody Sunday soldier told to "get some kills" murdered at least four civilians

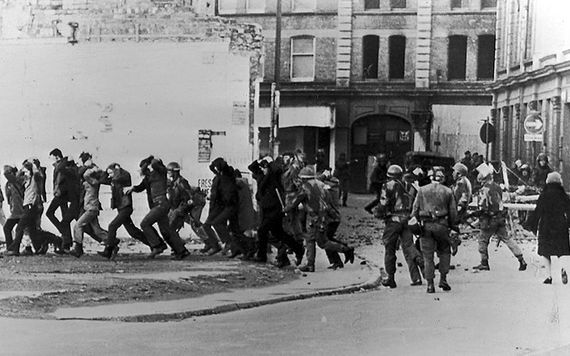

Funeral of Bloody Sunday victims. Image: Getty.

In the past two weeks, we have seen the enduring courage, love, devotion and determination of family members bear fruit in two cases known for decades as monuments of injustice: the Birmingham Six and Bloody Sunday.

On November 21, 1974, two IRA bombs went-off within two minutes of each other in pubs in the United Kingdom city of Birmingham. The explosions killed 21 people and injured 182. Six men from Northern Ireland living in Birmingham were arrested. They confessed under brutal conditions and were charged with murder.

Before confessing, the men were beaten, subjected to mock executions, burnt with cigarettes, threatened with police dogs and with being tossed-off a high building.

The main evidence against them at trial was the confessions. A false claim was made that some men had handled explosives. Perjured police testimony and spurious forensic testimony was also presented.

Two bombs in Birmingham in 1974 killed 22 people and injured more than 200 others.GETTY IMAGES

After conviction, Lord Chief Justice Widgery presided over the first appeal, which was dismissed. He found there was “no ill-treatment [of the defendants] beyond normal.”

In 1988, during a discussion about extradition, Irish Taoiseach Charles Haughey told British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher that Irish people do not get the kind of “reasonable and fair trial” in British courts that British people receive. He specifically referred to the Birmingham Six trial in this regard and asked her to consider “clemency” in the case. In denying the request, the Prime Minister said she had read the court judgment and was “totally convinced by it.”

In another appeal three years later, however, Crown prosecutors did not contest the men’s challenge to the forensic testimony and confession evidence. This time, the Court of Appeals found the convictions were “unsafe and unsatisfactory,” and quashed them. The men were freed from prison.

One result of this miscarriage of justice was the creation of a Criminal Cases Review Commission, which can consider a matter after appeals in a case have been exhausted.

Margaret Thatcher. Image: Getty.

Twenty-five years later, an inquest to investigate the Birmingham pub bombings was resumed after a campaign by family members of the victims who felt their loved ones had been forgotten.

The original inquest had been closed before completion after the convictions at trial. But innocent men had been convicted. No one else had been charged. There was a suspicion that the police knowingly made a case against innocent men in order to protect an IRA informant who had provided them advance knowledge of the bombings.

One family member, who said her “world fell apart” when she lost her older sister, explained: “This campaign is a campaign done in sadness and not in anger for those who are not here to fight for justice for themselves. Twenty-one people were murdered in cold blood. They have no voice; they have no opinion, but we are here and we can fight for them.”

Family members viewed the inquest as providing new hope for learning the “truth” and seeing perpetrators held “accountable.”

Despite delays due to court challenges and funding issues, the truth seems to be emerging at the ongoing inquest hearing. Testimony at the inquest described the pub bombings as “an IRA operation that went badly wrong.” Four alleged IRA bombers have been named. Some of them have died. Nevertheless, family members expect the police to follow-up on the new evidence.

Read more: Why “England Get Out of Ireland” banner belongs in New York Parade

The family members of Bloody Sunday victims. Image: Getty.

Having overcome many obstacles, their journey of acknowledgment and truth-recovery continues. It remains to be seen whether they will be able to go as far as the Bloody Sunday victims’ families have traveled.

On January 30, 1972, British soldiers in the First Parachute Regiment opened fire on non-violent protesters in Derry, who had assembled to march against internment. Within half an hour, 13 unarmed civilians lay dead on the ground. A 14th citizen died from gunshot wounds shortly afterward.

The infamous day is known as Bloody Sunday. The murders committed by the soldiers ended the civil rights movement and any hope that Northern Ireland would be transformed peacefully.

Lord Chief Justice Widgery was appointed to lead a tribunal to determine what happened. He failed miserably. The Widgery Report completely and unconditionally exonerated the soldiers. The report determined that “there was no reason to suppose that soldiers would have opened fire if they had not been fired upon first.” Following this “whitewash” of the deadly events, it would take 38 years to correct the record with the truth.

When family members of the victims launched the Bloody Sunday Justice Campaign in 1992, they had three goals: to overturn the Widgery findings and have a new inquiry conducted, to win formal acknowledgment of the innocence of their loved ones, and to prosecute those who were responsible.

The first two goals were achieved in 2010 when the Lord Saville Inquiry rejected the Widgery findings. The Saville Report explicitly acknowledged the innocence of the victims and the guilt of the soldiers. The report concluded: “[S]oldiers of 1 PARA on Bloody Sunday caused the deaths of 13 people and injury to a similar number, none of whom was posing a threat of causing death or serious bodily injury.”

It placed responsibility on the soldiers “whose unjustifiable firing was the cause of deaths and injuries.”

When the report was made public, British Prime Minister David Cameron apologized to the families for “the pain and hurt of that day, and a lifetime of loss,” noting it was clear that the soldiers had acted “wrongly.”

Bloody Sunday. Image: Getty.

After the Saville Inquiry, family members continued to pursue accountability for wrongdoers. “You can’t draw a line on murder. Justice has to be seen to be done, no matter how long ago it was,” one said.

Recently, some of them achieved their third goal when the Director of Public Prosecutions for Northern Ireland found “sufficient evidence” to charge a 1 PARA soldier with murder and attempted murder of six people on Bloody Sunday. The news that a single soldier was going to be prosecuted received mixed reactions among family members.

Some were heartbroken, others disappointed. Those whose loved ones formed the basis of the murder charges felt they had achieved justice for all Bloody Sunday victims. And one family member expressed “forgiveness” for the soldier. He said, “[p]utting the soldier in jail wouldn’t make me happy whatsoever.”

Instead, he wanted to see the British establishment and unionist leaders of the day who called the paratroopers into Derry placed on trial.

These reactions to the news of the prosecution may differ. But they show that deeply raw and painful feelings still resonate after 47 years. Lingering hurt and heartache are not unique to high profile cases. They are universally held by anyone suffering a similar trauma.

That should be a lesson for political leaders who must decide how to deal with the legacy of the past and 3,000 unsolved murders during the Troubles. As Nobel Peace Prize recipient and Chair of the South Africa Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, has noted, “the ghosts of past” must be dealt with “so that they will not return to haunt us.”

The long delay in implementing the terms of Stormont House Agreement means a mechanism for dealing with Northern Ireland’s past is not in place, denying victims’ families a chance for truth and justice to be rendered.

On an individual level, this undermines their ability to heal.

On a societal level, this undermines the rule of law. It also sows seeds of resentment and distrust, negating opportunities to foster reconciliation between the two communities and move Northern Ireland forward toward a shared society.

It is time to act.

What are your thoughts? Let us know in the comments section, below.

This article was submitted to the IrishCentral contributors network by a member of the global Irish community. To become an IrishCentral contributor click here.

Comments