The scale of the British dirty war in the north is finally destabilizing long-held southern political platitudes - and it's about time.

How we talk - and don't talk - about the North tells us so much about how we feel. In the lead-up to the 2022 Oscars, for example, we are going to hear much more about Kenneth Branagh's semi-autobiographical film "Belfast."

There is so much to admire about the film. The central performances by the talented cast, including Jamie Dornan as a frequently absent but always heartfelt Pa, Caitríona Balfe as the flinty but courageous Ma, Ciarán Hinds in one of the best onscreen performances of the year as Pop, and the flirty and ferocious Judi Dench as Granny.

And there is so much to regret about the film, too. “Belfast” treats the pre-Troubles city as a kind of Eden, with an opening number straight out of Oliver Twist featuring caffeinated young people playing just a little too cheerily on the idyllic working-class streets.

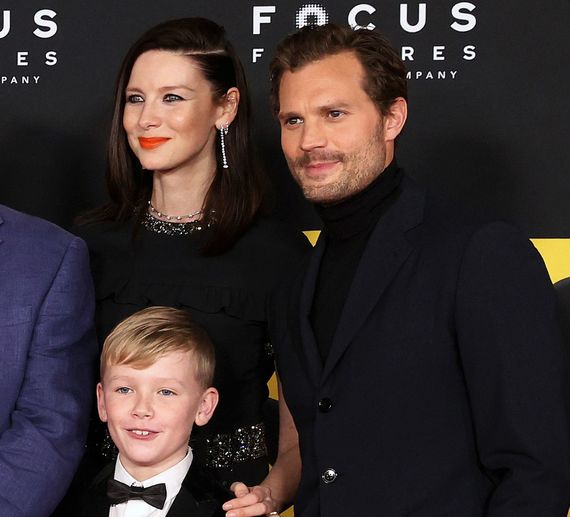

Caitríona Balfe, Jamie Dornan, and Jude Hill from "Belfast." (Getty Images)

Worse again, in a film that is titled “Belfast” and not “My Street Before We Scarpered,” the sudden appearance of torch-bearing loyalists is treated as a kind of inexplicable zombie attack – they just arrive onscreen without comment or context - and not as the result of systemic state violence.

If you call a film “Belfast” and your theme is the emergent Troubles, shouldn't there be some impetus to tackle the root of the issue, even with some broad strokes? Instead, unfortunately, Branagh's screenplay suggests the violence is mostly the work of some mustache-twirling local loyalist rotters, who mislead the credulous and create all the mischief.

The revisionism continues with Black Hat, White Hat showdowns a la “High Noon” between bad Protestants and good Protestants in a sequence that was so reductive, so bluntly ahistorical that it made me gasp rather than cheer.

The musician that Branagh refers to repeatedly to help tell the story of the times is Van Morrison, the famously apolitical singer who refused to address the carnage on the streets that he grew up in for decades and for most of his career in songs like “Bright Side Of The Road” and “And The Healing Has Begun” seemed to be in full flight from it.

Ciarán Hinds, Kenneth Branagh, and Judi Dench. (Getty Images)

It's interesting to make a film about an emergent civil conflict and the biggest ethnic clearance in Europe since 1945 and not take a political stance. Or it's worse than that, it's a cop-out.

Branagh can claim he was simply telling his own family's story up to the moment that they leave the north for good, but shouldn't there have been a bit more context about why they make that decision and why their society has forced them to? The silence in an otherwise rather loud film is deafening.

But that barge pole distancing isn't Branagh's alone. Over the years, many Irish songwriters have addressed the Troubles with varying degrees of success and solemnity. In recent times though some of those banner songs are now being reassessed as the expression of schism rather than solidarity.

Written when the band's lead singer was just 22, the Cranberries famous “Zombie” track reminds us that in the increasingly prosperous and politically stable Republic, the conflict in the north was an atavistic deathmatch with no point or purpose.

The lyrics assured northern nationalists that the violence was in their “head” and suggested, none too subtly, that they were all mindless “zombies.” The song was written as a response to the horrific Warrington bomb, but it widened its frame of reference as far back as 1916.

Lyrics like this simply gaslighted the lives experience of northern nationalists, who found themselves on the receiving end of extraordinary state violence for daring to agitate peacefully in favor of modest social and political reforms.

These oppressions were not “in their head,” they were not abstract romantic nationalisms without substance or purpose, they were ubiquitous oppressions that genuinely blighted their lives and it's a shame that fact still has to be reiterated.

But southern Irish journalists who are quick to defend the Cranberries and bands like U2's rather blunt lyrics in "Sunday Bloody Sunday" have been much more notably reticent when it comes to the Northern Ireland Police Ombudsman's report unveiled last week that showed longstanding police and loyalist collusion.

The evidence of “collusive behavior” between police and loyalist paramilitary groups in 11 murders and 16 attempted murders in Northern Ireland during The Troubles appeared and vanished in the southern broadsheets without much hand wringing over the implications.

Even when it was confirmed that the UDA gunman who massacred five civilians in the Sean Graham’s betting shop attack was working for Special Branch there was barely a murmur in the southern broadsheets.

It's hard to think of another police service in the western world where police and paramilitary planning in the deaths of local civilians could merit much more than a disinterested shrug in the national press, where the revelations languished or went under-reported and soon stopped.

Meanwhile, instead of initiating further investigations, the British government clearly wants to shut these damaging reports down, including ending all legacy inquests and civil actions and preventing the Police Ombudsman from examining Troubles-related incidents.

It seems that the British dirty war in the north is finally destabilizing the long-held southern journalist contention that the violence was all the work of irredentist republican paramilitaries and their unattainable romantic dreams.

It is to be hoped that the new mood of engagement rather than estrangement lasts in southern journalistic and political circles, where the nation's history and its partition – and the discriminatory history of the unionist run six counties - keeps resisting all attempts at latter-day airbrushing in Leinster House.

It might be wise too. With a majority of people in favor of holding a border poll in the next five years, and Sinn Féin's rise looking certain to reconfigure the political map north and south, the issue of Irish reunification isn't just the "mystical blather" that writers like Colm Tóibín assert it is - but rather it is firmly back on table, so suddenly half-baked platitudes, condescension and gaslighting just won't cut it anymore.

Comments