It's the 100th anniversary of the publication of James Joyce's "Ulysses," and its impact is being reconsidered by a stunning new exhibition at the Morgan Library in New York City, curated by Irish fiction laureate, novelist Colm Tóibín.

James Joyce published "Ulysses" on his 40th birthday in 1922 and now a new exhibition at the Morgan Library in Manhattan - curated by novelist Colm Tóibín - marks the centenary of the book's publication, as well as the heroic struggle the late Irish author made to write, revise and get it published.

"One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses" will run through October 2 and Tóibín's aim is to illuminate the author’s creative process through rare publications, portraits, correspondence, manuscripts, plans, and proofs taken from the Morgan’s Sean and Mary Kelly Collection - many of which are being reunited here for the first time in a century.

“I suppose it's got three different strands,” Tóibín, 66, tells IrishCentral. “One is to tell the story of James Joyce, and one is to tell the story of the reception of the book 'Ulysses,' but the thing that matters most is to tell the story of the composition of the book itself.”

Fighting censorship of the book after its publication took up years of Joyce's life and helped change what we can read or write in literature now. “I think that one of the big things that's changed is the novelists have the right to write about sex in a novel without everyone going nuts,” Tóibín says.

“I mean, when we look back on it, there really is very little in Ulysses that that really could frighten you, it's a challenge stylistically but it's not as though it's a big pornographic novel. But of course, he was breaking barriers.”

What Tóibín brings to his new exhibition at the Morgan is a writer's eye for the illuminating detail. “Sometimes if you're a novelist, you realize that something very big came from something very small. And that inspiration is strange. And we see it in Joyce, where we have a letter, an early letter from his partner Nora Barnacle and what's notable about the letter is that it's short, but it's also got no punctuation. She just doesn't bother, she lets it all flow. And you can see how somebody looking at it would think, 'Wow, imagine if you did that in a novel? If you let the voice flow?'"

Joyce wrote "Ulysses" as an exile and the lighthouse gaze of the outsider is manifest on every page. So what will the immigrant Irish living here take from the exhibit?

“I think it's an important exhibition for anyone who lives outside Ireland who's Irish because it was made by someone Irish living outside Ireland. And one of the things about it is that, of course, his memory was very sharp for the things that he felt he had lost."

"And it wasn't necessarily nostalgic, as much as he could see it more clearly, in certain ways, because he was now living in Trieste and then in Zurich and then in Paris. I spoke to someone whose father had met Joyce in Geneva in the 1930s and I said what did he talk about? He replied, 'Oh James Joyce just named places in Dublin and said is that still there, it that?'

“I think anyone who's Irish or Irish American knows the idea of once belonging to a place and wondering is that turn in the road still there, is that a tree still there, is that house or person still there? And of course, as I say, it's there at a particular intensity, because he's not living it anymore. He cannot take it for granted.”

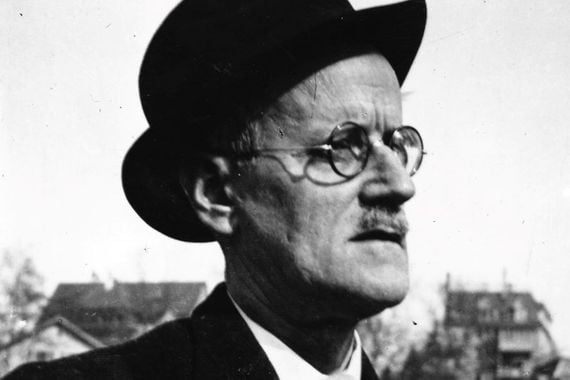

Irish novelist James Joyce. (Getty Images)

Tóibín is writing a sequel to "Brooklyn." I ask about the fateful decision Saoirse Ronan's character Eilis has to make between American-born Tony and Irish Jim, two signposts to two different lives she has to choose between.

“I think that everyone who came to America had an alternative life, even if it's just you know a girl that you went out with one night. But it was a great night. And if you had stayed you might have seen her again. And you think about her because the whole business of immigration is that it's not just looking to the future, it also can be filled with regret that the things that might have happened.”

“And it gives you a way of imagining your past as well as your future. And so yeah Jim represented solidity, stability, hometown. He's a solid guy. But the problem is Tony in Brooklyn is also a solid guy. And this gives her sort of energy, eventually, you know, she's starting out afresh, but always there in the background is that “I could be waking up in the morning, with the Irish news on, with Irish food, with Irish voices with Irish accents and with someone I love as Irish with walking out into the street where everybody knows.”

Does Tóibín feel pressure about matching expectations for "Brooklyn" part two? It has to have its own impetus, its own reason for existing, rather than just being a sequel, he says.

Domhnall Gleeson and Saoirse Ronan in the film adaptation of "Brooklyn."

Meanwhile, his aim with the Joyce exhibit can be simply put. “If you're a scholar, then you will say, 'Oh my God, I hadn't seen that manuscript before.' But my aim is also to write explanatory notes that would be absolutely clear to someone who just wandered in, who wanted to see the Morgan building itself and then wandered into this.”

In your own work like "Nora Webster" and "Brooklyn," you highlight the power of music to reorientate you, I tell him, to point you back toward yourself and toward life.

“You see, I'm a bad singer,” he smiles. “And there's nothing worse than a bad singer. Like being a bad poet. So when I was thinking about Nora Webster, who's a widow, she has a singing voice she has never really done anything with. She decides to actually go and get singing lessons. And she wants to be in a choir. And so it becomes a big part of, I suppose, restoring her sense of self or refining herself, that she does it. She does it through music, which I think is something I've seen happen.

"And it's something I thought would be dramatic and interesting in a novel.”

Grief can catapult you out of your life. In his own childhood, Tóibín lost his father early on, but in "Nora Webster," he doesn't want us to know where the autobiography starts and fiction ends. I asked him how he finds a way toward the working out of it.

“What I was interested in, I suppose, was the idea of how ordinary life is meant to replace this shocked world of sudden loss, sudden grief. And it does, and then it doesn't. And so you go back to school, everyone goes back to work, everything goes back to normal.

“What happens, however, is that you're trying to keep away very dark thoughts indeed, that come sweeping over you in ways that you cannot understand sometimes, and you can't predict. And so you're walking on the street, and suddenly it comes back to you.

"And anyone who's been through this loss, especially loss I think in childhood or early adulthood, where it's not what you expect to lose a parent, and nobody has a blueprint for how you should think or behave, or feel. Nobody knows what you should do. And people think you're always doing very well, he's fine. He was getting over it, or she's getting over. It's never true.

“And so I think it's something you can do with a novel because a novel is very good at dealing with private thoughts, things that you keep to yourself, if you don't talk about, you can actually put those in the novel.

"And it's curious that among all the other things in 'Ulysses' is that question of grief, postponed grief, and grief not entertained, is really an important element in the, in the life of Stephen Dedalus, as he walks around Dublin and the in life of Leopold Bloom.”

"One Hundred Years of James Joyce’s Ulysses" will run through October 2 at the Morgan Library.

Read more

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

Comments