Gabriel Byrne's new show on Broadway "Walking With Ghosts" is one of the richest meditations on Irish life I have seen on a stage in years, a story you'll carry with you long after the lights come up.

What critics here in America might not understand is the why. Why is this most private of men laying the lessons of his life bare on stage in this way, now? What has compelled him to speak up when it would be all too easy to rest on the laurels of a notably successful career?

The answer is much clearer to the Irish themselves. One of the journeys the new Republic is currently making is toward a national reckoning with itself, and in particular with the clerical abuse crisis, one chapter of which gets a searing retelling here.

In Ireland, over the last three decades, there has been a collective dam burst or glacial crack that has allowed our muzzled selves to finally speak up in a generational truth-telling exercise on which this show - and the memoir on which it is based - makes an unforgettable contribution.

It's extraordinary to witness this famously private man open up on stage, sharing details so intimate that you suspect it may have taken half a lifetime to address some of them, never mind discussing them onstage.

Strangely, watching it feels like our first real introduction to the man in full. Others may have seen this lyrical and screamingly funny private side of him before, but it will be news to those of us who best remember him from his often memorably dark work with A-List art house directors like the Coen brothers, Wim Wenders, and Jim Jarmusch.

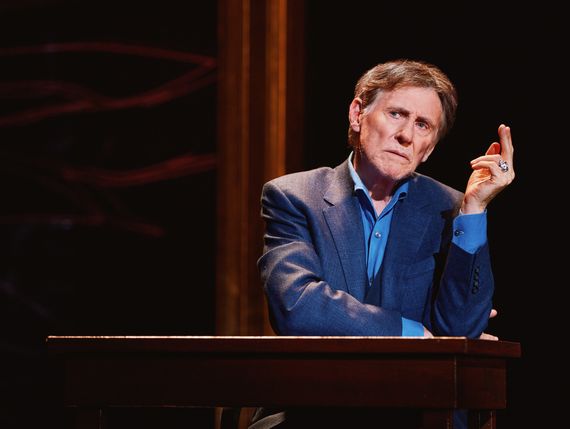

Gabriel Byrne in Walking With Ghosts

Just a few days before his one-man show opens on Broadway, actor Gabriel Byrne is in fine form in the foyer of The Music Box Theatre on 45th Street, which this afternoon is busy with the show's crew, who are making last-minute improvements to the sound and lights.

Already Byrne's one-man show (based on his memoir of the same name) is a critical darling, having wowed London and Dublin during its sold-out tour. That's probably why a relaxed, smiling Byrne greets me today, already safe in the knowledge his show is a box office success, and let's hope the reviews will be positive. Early indications give him grounds for optimism.

"Walking With Ghosts" is a memoir of his life and times, but at root, it's also a love story. Byrne, a youthful 72, speaks of his great love for his family, for the amateur dramatic circles that once helped him escape his own solitude and step into himself, for the city that was brimming with characters and stories to study, and for the nation that still helps him take the measure of his long journey.

If, as Byrne tells us his father used to say, “you can tell a lot about a man from his shoes,” then you can tell a lot about Byrne himself from the depth of the love he clearly has for the people who populate his memories and this performance.

It's a love story, I tell him. It's not really about his fame and fortune, it's about the things that have really mattered. The things that make a life.

“I never thought of that,” he tells IrishCentral. “But I would be honored by a description like that. Because, you know, there's nobody on that stage is still alive. Not one person. So that's why I say to friends of mine, you can come without concern because it's not about anybody who's alive.”

“But it's in a way I'm having a conversation with those people. I mean, when you're having a dinner party people will often ask you if you could invite anyone who would you have there? And I always think to myself, I wouldn't be interested in Abraham Lincoln or whatever. I'd love to have my father, my grandfather, and my great grandfather, to just sit there and ask them about their lives, and all the things I never got to ask them when they were alive.”

Gabriel Byrne goes Walking With Ghosts on Broadway

That halting conversation has been going on for many years, Byrne's play shows us. With the passing of time and the wisdom of experience some things that were missed back then come into sharper focus now, Byrne says.

“In the last section of the play, I am having a conversation with my mother. And I'm saying, were you really happy? And did you know me? And did I know you?” Fearing the answers when she was alive for what they might mean for his own development, he is impressively self-aware and truthful in his interrogations then and now. Like most of us, but perhaps especially the Irish, he seems to be haunted by the why's and what-ifs of the past.

“I realized things about my father. That I never really listened or only half listened to him. It's only now that I finally hear him. And that makes me think, you know, what would I say to my father now? What do I remember about him? I remember his humor and his kindness and how difficult it must have been at 48 years of age to be thrown out on the dole, really. To have his pride in himself and his contribution taken from him like that.”

But don't think that this is a morbid recreation of a hard past. “Nor is it nostalgic in a kind of a fake way,” Byrne explains. “It's about saying these were the things that brought me joy and sorrow in my life. And my intention, always from the beginning, was to tell the story of a place and time.”

Byrne really has no interest in saying, “Okay, this is my story, let me stand up and yeah, look at me, look at me,” he says and I can vouch for that, having just seen the show. There is very little in it about his remarkable screen acting career or the people he dated. This is not another celebrity kiss-and-tell. This isn't even a story that's all that interested in celebrity. That's just a mask some people put on and discover they can never take off, he reminds us.

“I talk about some things that are hard to talk about in the show and maybe by saying these things, you will be able to take away something from it into your own life. I talk about my parents, I talk about the things when I was young that brought me joy. I talk about the things that formed me, like for example, that abusive Christian Brother, you know? That was a form of sadism and violence under the guise of education.”

“And people will say, “Oh, yeah, they were cruel but that's all gone now.” But the truth is nothing on that stage is gone now. Maybe they don't need canes now, they have more sophisticated ways of doing it (traumatizing the underclass into silence and rigid conformity).”

“The point of continually traumatizing young working-class men is to get them into thinking in a particular way, to teach them to keep their place and not get above themselves you know, don't get notions about yourself.”

Gabriel Byrne in Walking With Ghosts

Byrne has made an epic journey that kids from his background weren't supposed to make, so he had to make his own path up. How did he find his way? Was it harder for him because there was no map?

“It's a good question,” he replies. “Maybe if I had been one of those people who bought into fame - and I did buy into it for a very long time - but that stopped. Growing up I was told that the best thing you could do in life was to get a permanent job, get a trade, and get into the civil service. Now I think that there are two kinds of immigrants and maybe they're all kind of mixed up together. There's the immigrant who has to leave because there are no jobs, there's no work, he has to get on the boat and go in a kind of a forced exile.”

“And then there's another kind of immigrant, the guy who knows somewhere deep down that he doesn't want to be in this place for the rest of his life, despite what they're telling him. And that there is this sense of wonder just beyond. I've been both.”

Whatever the American critics decide about "Walking With Ghosts" this week, Irish audience members will hear and see themselves reflected in this from the depths story. Here is a man who has been given many gifts and now wants to share some of the best of them. It's often as simple and as beautiful as that.

"Walking With Ghosts" is now playing at The Music Box Theatre on Broadway.

Comments