Long before the American Civil War, Irish immigrants and Black Americans lived – and often loved – in the same notorious slum neighborhood of the Five Points in Lower Manhattan.

Now a new musical called Paradise Square takes us back to a time when an all too brief racial harmony was undone by a nation increasingly at war with itself.

Racism has been a fact of American life since Christopher Columbus first stepped off the Santa Maria in 1492. But Paradise Square, the new musical by Black 47's Larry Kirwan is not here to lecture you for two hours about America's racial injustice.

“I've always been interested in the Five Points neighborhood and its history,” Paradise Square songwriter Larry Kirwan tells IrishCentral. “I was interested in the Irish immigration here during the famine era and of course being a musician I was also interested in Black music.”

The path to Paradise Square took decades. One inspiration was a series of etchings he uncovered in an old history book that showed some of the African American Dance Halls in the Five Points in the 1850s. In particular, he was fascinated by the racial makeup of the house bands.

“It was always two Irish people and two African Americans, the Irish person playing the fiddle and singing and the African Americans playing banjo and doing percussion. I began to wonder, what did they sound like? Then I began to look at the faces of the dancers.”

There was usually a Black man and an Irish woman dancing jigs, but it was always the same look on their faces. “I could tell that the artist was trying to portray something, that these people were in love. I didn't know about the high rate of intermarriage between Black Americans and the Irish at the time of the Great Hunger.”

In fact, interracial marriages and relationships were so common that Kirwan later discovered they had a name, amalgamation. But that harmonious era ended abruptly with the notorious Draft Riots on July 13th, 1863. “I thought the story of the time was perfect for drama, so I wrote a musical called Hard Times which got produced a couple of times at the Cell Theater on 23rd Street in Chelsea.”

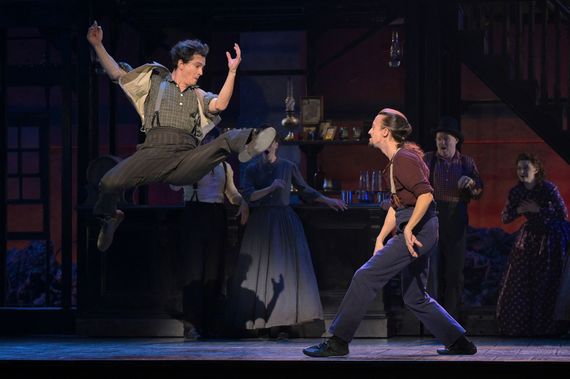

That was all it took. “I put in some more characters that Garth wanted, right from the start. He made it clear he wanted a big show because this is a big subject. He wanted to see the Draft Riots. He wanted to show the way they had danced. Tap dancing had been created through competitions between the Irish step dancers and the African American Juba dancers, but the show delves into the whole history of what happened between them."

"Then theatre legend Bill T. Jones came on board to do choreography. And Hammer Step, the Irish step dancers supplemented his work. Then the director Moises Kaufman came on board as the show expanded. None of this would have happened without Garth's drive.”

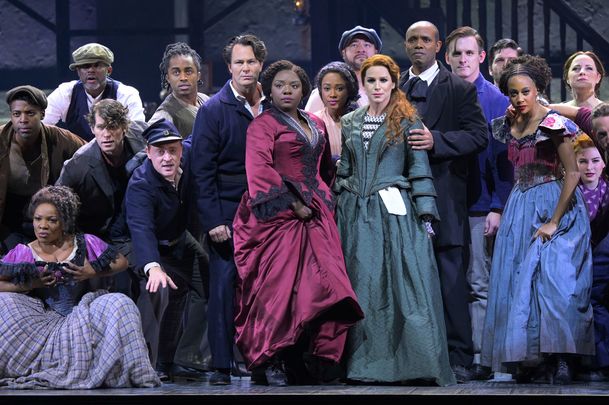

“At this point, after five years, what we have is just an amazing cast, Kirwan adds. “And although the show got held got held up by Covid, I think it only deepened it in certain ways.”

Why does Kirwan think the early years of Irish immigration and the racial relationships that defined them are so underappreciated today? “Well, one of the things that you know yourself is that Irish people love Black music. Especially Irish musicians, we were kind of raised on it. When I came over here I was into all the Black writers and players. Curtis Mayfield is still one of my favorites, you know?”

“I think the reason that Irish people don't reflect much on those years now is because things were severed on July 13th, 1863, and afterward neither side wanted to talk to talk about it,” Kirwan explains.

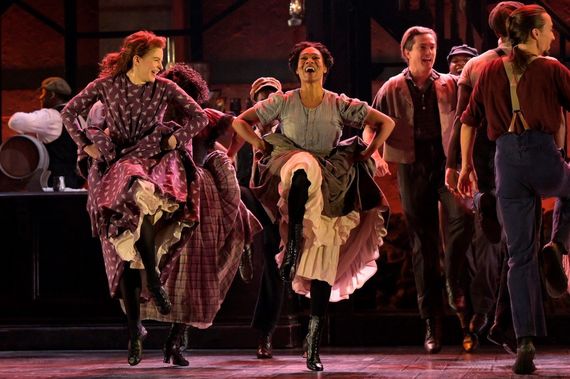

A shared love of dance lit up the Five Points in the 1860's

The world and America look fractured to us now Kirwan says, but it's nothing compared to the Civil War era. “We have a lot more in common with each other than we think and the musical addresses that. When you see this great cast on stage who are totally familiar with each other and there's no real color difference at first, I think there's a way that the musical can really address the situation that's out there in the country right now.”

His own background as a writer and musician was training for this moment, Kirwan reflects. “I was a playwright before Black 47 and all the time during Black 47 I kept writing plays, but I began to drift more towards musicals because I also write songs.”

It was a challenge, he admits. “Musicals are really difficult to write. There's so much balancing between the music and the book and lyrics. You asked why the Irish don't write more of them and I don't know. There was probably a cutoff, because if you take vaudeville – which came out of the Five Points - the Irish were vitally involved in that with their music and with the Jewish people and the Black people. But somewhere along the line, Irish people went back towards straight drama, and I think it was maybe because of the strength of it.”

Kirwan continues: “One thing I would like to point out is that if the Irish artists haven't embraced musicals, Irish people have. They're turning out big time for Paradise Square and they love it. I think it's part of their history to them.”

Paridise Square is now playing on Broadway

"They were kind of letting the side down, coming here diseased and starving and with no money. They flooded the town. They kind of wrecked the place. I remember the writer Pete Hamilton explain the reason we were called the dirty Irish was because there was no place to wash.”

But amid the squalor, there is beauty too. “There's a point in the first really big dance number, about 20-way minutes into the show, where one of the Irish dancers looks at this beautiful African American woman. They've obviously seen each other on the streets and there's a lot of recognition in both their faces."

"There's also a look of admiration and they do a dance-off. You see how it probably happened. The attraction between the Irish and the African Americans in those dance halls. You see it in front of your eyes and to me, it's one of the strongest moments in the show. You don't have to talk about amalgamation, it's right there in front of you in the dance. And the dancing is spectacular.”

Paradise Square is now playing on Broadway.

Comments