|

|

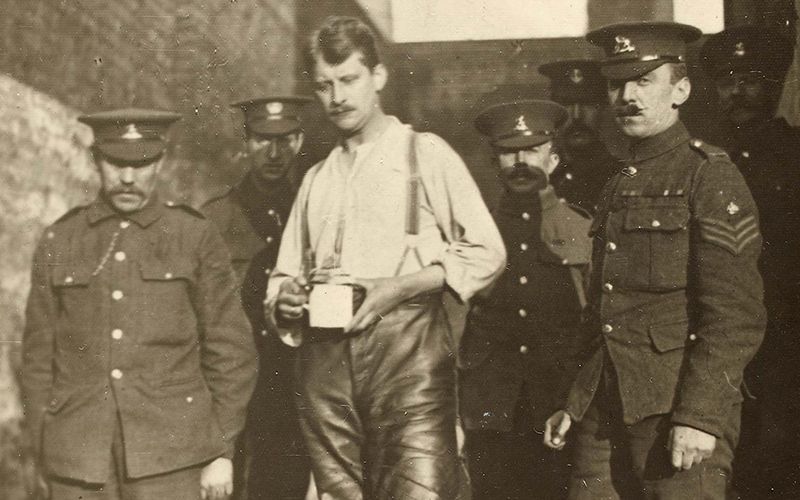

Irish actor Michael Mellamphy gives a tour de force performance in Conal Creedon's The Cure.

|

|

The Cure

By Conal Creedon

1st Irish Theatre Show

It is a truth universally acknowledged that the more insightful and accomplished a new Irish play is, the less chance it has of being produced on Broadway.

The major American critics love Ireland. The picturesque Ireland of early 20th century Irish drama, that is.

The truth is they usually don’t know very much about contemporary Ireland, nor do they welcome the complicated challenge it presents to their old certainties. They certainly don’t know much about its contemporary playwrights.

I don’t know why Conal Creedon hasn’t been produced on Broadway yet. Certainly his plays are as deserving as any recent work from Ireland that has made that cut. In fact, he has more to say, more concisely, than just about any of his dramatic contemporaries.

That thought struck me watching the gifted actor Michael Mellamphy’s performance in Creedon’s deceptively straightforward one act drama The Cure this week, which is being presented as part of the exciting 1st Irish Theatre festival.

On the surface The Cure is a charged monologue about a luckless man drinking his seasonal bonus pay on a three day bender in the lead up to Christmas.

But as the play progresses it becomes an absorbingly rich meditation on generational poverty, colonial exploitation, masculinity, sexual repression and the reflexive Irish cure-all, booze.

Creedon, the play reminds us, knows Cork intimately, from the unique aromas of each street to the important nuances of the Hiberno-English spoken on them. I can’t think of another writer who can conjure the city so vividly.

As our narrator (Mellamphy) winds his way through the city streets in search of the cure for his hangover (more booze) he encounters the old Christian brother who terrified him as a child, giving rise to questions about what happened to him and who he’s become.

Mellamphy inhabits his character so completely that he gives an electrifying performance. He also plays the characters that the narrator encounters, magically transforming himself to present a snapshot of the community.

It’s amazing how much Creedon actually packs into this rueful tale without harming its central premise. Although The Cure is most concerned with the ways class and history and oppression conspire to blight the lives of the innocent, he also manages to explore how the generations tangle with each other over ever diminishing expectations and opportunities.

Learned helplessness is one of the notable characteristics of a postcolonial society and it is everywhere in The Cure. Generations of Irish men see life as an increasingly meager speculation, the play reminds us, without ever understanding the bigger picture or their place in it. Instead they’re just left to flail and scramble on their own as history keeps on passing them by.

But Creedon knows there’s another story that could be told and he gently steers his narrator toward it, toward the bigger cure than the one that can be found in pubs. It’s a welcome reminder that a new generation of Irish playwrights are writing about modern Ireland free of the imprisoning traditions so beloved American theatre critics.

This production, nimbly directed by Tim Ruddy, deserves to be seen by a wide audience.

The Cure is playing at Ryan’s Daughter, 350 East 85th Street, New York. Visit www.1stirish.org for tickets and showtimes.

Comments