History, just like geography, has a way of always getting in front of you. It can help shape your perspectives, your character and even your accent long before you get wise to the fact.

In Northern Ireland this is especially true. If ever there was a place where history keeps playing out on a loop tape over and over, it’s there.

So the most challenging thing you can do, in a place that’s reflexively repressive, is try to write your own story or step outside the one you’ve been handed at birth. Mold breakers more often find it’s themselves who are being broken there.

Like a lot of young people growing up in the North in the 1980s, writer Colin Broderick found the imprisoning claims of his community (and his family) increasingly suffocating. Their expectations were laid out early and it was made clear there would be no exceptions. The game had been rigged before he was even aware he was a participant.

In his new memoir 'That’s That' (Random House), a reference to the phrase his mother used constantly to discourage his teenage self from asking increasingly awkward questions, Broderick paints a portrait of a community in crisis.

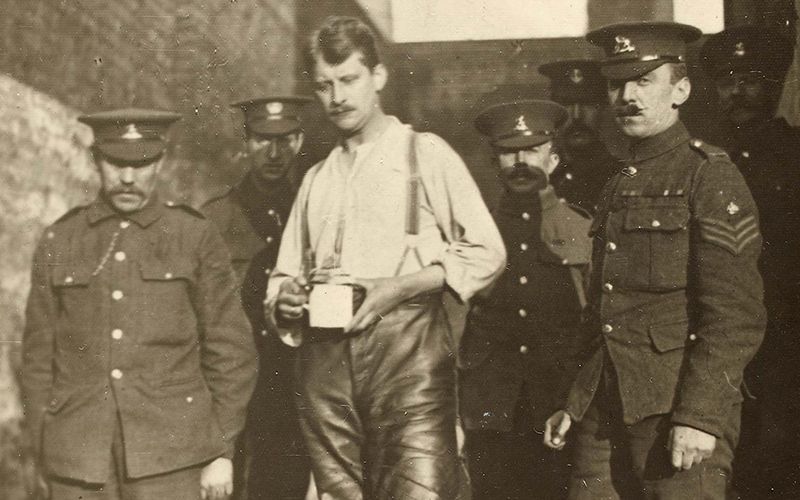

What’s interesting is that the people he writes about in 'That’s That' try to live as though they’re not in crisis. They may be poor, they may be surrounded by trigger happy police and soldiers, they may be tied to a wider conflict they didn’t start and can’t end -- but they have immense pride and they live, or try to live, as if none of it is happening.

It was happening though, and it was increasingly inescapable. In fact in 'That’s That' the demands of history are actually so consequential that Broderick actually opens the book by meditating on the history that created the conflict in Ireland in the first place.

It’s not such a grandiose move. To Irish people The Troubles and their legacy are as familiar as their national flag, but to most people born outside of the island it can look like an atavistic bloodbath with no real purpose and no end. We see a centuries old facedown between Gael and Planter, but the world sees pasty white people killing other pasty white people, and they just scratch their heads.

To make sense of his present Broderick mines his past. There are so many telling episodes from his childhood and adolescence to choose from in 'That’s That' it’s a wonder how he survived at all.

The first stirrings of desire are accompanied by bone deep religious panic and mortifying shame. Childhood innocence is discarded too soon, as though it didn’t matter, and throughout it all there’s the ever mounting pressure of his own spirit pressing back against the straight jacket his society wants to put him in.

When you grow up in a place that is making it increasingly clear it has no place for you, when you’re surrounded by choices that aren’t really choices at all, there’s only two things you can do. You can accept your lot and wrap your community around you like a blanket, or you can turn tail and run away as fast as you can.

Wisely, Broderick chose to run. But as 'Orangutan,' his first memoir made clear, it was no easy task.

In the North they often talk about the peace process, but they rarely ever talk about the peace you have to make with your own past. 'That's That' makes a point of it. The political cost of the conflict is visible to all, but its emotional cost has hardly appeared in print until now.

In fact Broderick’s reactionary tailspin lasted almost two decades until he finally surfaced and found his new life. To dull the pain and to outrun the demons he did what generations of the Irish did before him -- he kept moving, and when that didn’t work he turned to drink, the Irish anti-depressant.

'That’s That' is Broderick’s apotheosis. It’s the hard won testament he brought back from his broken past.

It turned out that it was love and not war that shaped him, but it can take half a lifetime to figure that out if the world you grew up in was daily rocked by bombs and barbarism.

In 'That’s That' Broderick does something that takes remarkable courage, he tells the truth. It’s the ultimate revolutionary act.

It isn’t his parent’s truth or his community’s truth. It’s his own, and it’s unassailable.

In Northern Ireland this is especially true. If ever there was a place where history keeps playing out on a loop tape over and over, it’s there.

So the most challenging thing you can do, in a place that’s reflexively repressive, is try to write your own story or step outside the one you’ve been handed at birth. Mold breakers more often find it’s themselves who are being broken there.

Like a lot of young people growing up in the North in the 1980s, writer Colin Broderick found the imprisoning claims of his community (and his family) increasingly suffocating. Their expectations were laid out early and it was made clear there would be no exceptions. The game had been rigged before he was even aware he was a participant.

In his new memoir 'That’s That' (Random House), a reference to the phrase his mother used constantly to discourage his teenage self from asking increasingly awkward questions, Broderick paints a portrait of a community in crisis.

What’s interesting is that the people he writes about in 'That’s That' try to live as though they’re not in crisis. They may be poor, they may be surrounded by trigger happy police and soldiers, they may be tied to a wider conflict they didn’t start and can’t end -- but they have immense pride and they live, or try to live, as if none of it is happening.

It was happening though, and it was increasingly inescapable. In fact in 'That’s That' the demands of history are actually so consequential that Broderick actually opens the book by meditating on the history that created the conflict in Ireland in the first place.

It’s not such a grandiose move. To Irish people The Troubles and their legacy are as familiar as their national flag, but to most people born outside of the island it can look like an atavistic bloodbath with no real purpose and no end. We see a centuries old facedown between Gael and Planter, but the world sees pasty white people killing other pasty white people, and they just scratch their heads.

To make sense of his present Broderick mines his past. There are so many telling episodes from his childhood and adolescence to choose from in 'That’s That' it’s a wonder how he survived at all.

The first stirrings of desire are accompanied by bone deep religious panic and mortifying shame. Childhood innocence is discarded too soon, as though it didn’t matter, and throughout it all there’s the ever mounting pressure of his own spirit pressing back against the straight jacket his society wants to put him in.

When you grow up in a place that is making it increasingly clear it has no place for you, when you’re surrounded by choices that aren’t really choices at all, there’s only two things you can do. You can accept your lot and wrap your community around you like a blanket, or you can turn tail and run away as fast as you can.

Wisely, Broderick chose to run. But as 'Orangutan,' his first memoir made clear, it was no easy task.

In the North they often talk about the peace process, but they rarely ever talk about the peace you have to make with your own past. 'That's That' makes a point of it. The political cost of the conflict is visible to all, but its emotional cost has hardly appeared in print until now.

In fact Broderick’s reactionary tailspin lasted almost two decades until he finally surfaced and found his new life. To dull the pain and to outrun the demons he did what generations of the Irish did before him -- he kept moving, and when that didn’t work he turned to drink, the Irish anti-depressant.

'That’s That' is Broderick’s apotheosis. It’s the hard won testament he brought back from his broken past.

It turned out that it was love and not war that shaped him, but it can take half a lifetime to figure that out if the world you grew up in was daily rocked by bombs and barbarism.

In 'That’s That' Broderick does something that takes remarkable courage, he tells the truth. It’s the ultimate revolutionary act.

It isn’t his parent’s truth or his community’s truth. It’s his own, and it’s unassailable.

Comments