Roddy Doyle's latest short story collection "Life Without Children" contains vivid reports from the lockdown in Ireland, including the way it has roughly turned Irish life on its head. The result is some of the saddest and funniest works Doyle's produced in years.

The darkness that always chases after life is fairly sprinting in Roddy Doyle's new collection of short stories, "Life Without Children." Unavoidable middle-aged rights of passage like sudden, serious health problems, or prescriptions for something stronger than a headache, or unexpected and life-altering career challenges, or the pain of empty nest proliferate - and the news, when it comes, is not always uplifting.

But it's the long shadow of the coronavirus pandemic in Ireland, in particular, those panicky early days when many people were still Silkwood washing their groceries as the better-off fled to their homes in the country that really jumps off the page in this so vivid you are there new collection.

Read more

“In the hotel foyer he didn’t want to put his hands on the counter,” Doyle writes of one unhappily married father in the collection's title story. “He didn’t want to hand over his debit card.”

Caught in England as the Irish lockdown looms, this anxious man in his early 60s suddenly contemplates not returning to Ireland at all, letting the pandemic allow him to strike off in a new direction, rewriting his story.

Choosing between the life he never had and the life he has but doesn't want, whilst other people are going to ground he's thinking about striking out in a new direction entirely.

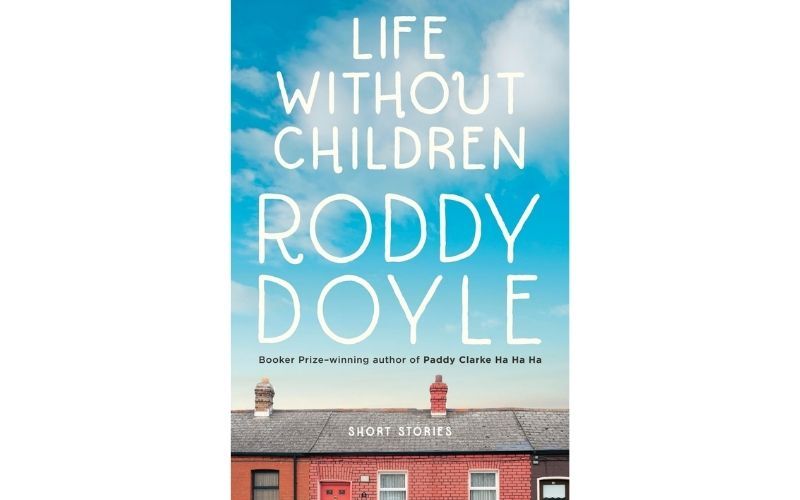

"Life without Children" by Roddy Doyle.

The dangerous gulf between England and Ireland's response to the arriving pandemic is a part of the story. So is the gulf between needing a new beginning and deciding to do something about it. As Ireland learns how to socially distance and mask up, the locals in Newcastle – where the title story is set – are still out on the town attending raucous stag and hen do's as though nothing bad is happening, or could.

So communication, or more precisely, the lack thereof, is really what's going on in these thorny and beautifully written stories, which have that rare E.M. Forster-like clarity of character and event but rarely ever heed his advice to connect.

Men, and in particular straight men of a certain age, aren't doing too well in these raw pictures from contemporary Ireland, where they have seen and mostly kept abreast of cultural and social changes but not so much the emotional changes in themselves.

Lockdown seems to have given the writer a shot in the arm, because these stories are full of people risking more of themselves, or seeing their lives implode from failing to take a risk, in a way that seems new and important in his work.

In prose clear as a mirror, Doyle identifies and conveys the festering disappointment that's curling around the edges of the man at the center of his title story for example by focusing on his father's legs at the beach and realizing that he has a similar pair now.

“They were pale - it must have been early in the summer - and they were hairless, unlike his arms and his chest - and there was a line like a river, a blue vein, running down one shin. He stood in front of the hotel room mirror and saw that vein in his own leg. He almost looked behind him, to watch his father coming out of the bathroom. His father had been dead for seven years. They were his own legs but he’d become his father.

“You’re a ringer for your dad. People had said it at the funeral. It’s f--kin’ uncanny. He had the legs of a dead man. I’ll say this, an old friend of his father’s had said that day, beside the hearse. He held on to Alan’s hand, and wouldn’t give it back. You’re not half the man your father was. I’ll leave it at that.”

This is extraordinary in its simplicity and effect. Doyle opens trap door after trap door for the man in this story to fall through. Even his reluctant decision to resume the old life he has – and hates – is another dispiriting pratfall. These aren't just men, they're open wounds and no one can seem to reach them, perhaps especially themselves.

The silence of the world of the pandemic, when people agree to stay indoors and the streets fall silent, is used to great effect by Doyle in this collection. One of his benighted male characters braves the empty streets, which have an eerie solitude that reflects the silence inside them.

It can happen that a man can get trapped inside himself and time after time we meet such men in these stories. Emotionally locked down or filled with almost uncontrollable rage, they oscillate between too little and too much and often alienate the people they love the most.

Not all stories have lost middle-aged men or sad endings, however. Stories of the everyday triumph of domestic love over events as rattling as a global pandemic are to be found here too and they remind you why Doyle became famous in the first place, through his celebration of the universal in the very particular, by making Dublin working-class life the key to all life.

Read more

Silence haunts the edges of these stories too. The silence of things unsaid, the silence that follows walkouts and their aftermath, the silence of a string finally snapping. But the biggest silence of all is here too.

“The Irish do funerals well, they say. Death doesn’t frighten the Irish. They know all the right words. He was a legend, a saint she was, a saint, he did great things for this place, I’m sorry for your troubles, I used to love meeting her, he’ll be missed around the town. They know how to sing. They know how to get drunk. They know how to stay polite for the day. If there’s genius, if there’s a national flair, it’s in the ability to get rat-arsed and remain civil and cute, to let go and hold back. To wait...”'

Some stories like The Worms, named after earworm songs that come back to us in the shower years and decades later, even if we don't particularly like them, tells the story of a couple in their sixties who somehow find each other again after years of parenting and mutual loneliness.

Set in the middle of the lockdown where the imagination and memory of the couple in question are finding endless time to remember long-forgotten songs and details, the husband and wife here also find what brought them together in the first place.

This is a story so pure that the language itself sings, bringing the man to a simple realization that has been lost amid the clutter of his daily life: how much he loves his wife. That may seem like a mundane discovery but in Doyle's hands, it has the power of a revelation.

One measure of love is loss, the tragedies and re-awakenings contained in this alternatingly heartbreaking and heart-lightening collection remind us. Even the dopey little pop songs of our youth contain precious gold if your eyes are open.

"Life Without Children" by Roddy Doyle, Viking $25.00.

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

Comments