Ireland knows all about moving statues and what they mean. Irish statues of Our Lady traditionally begin to signal and nod at awestruck locals when the country is facing acute economic anxiety.

These extraordinary revelations always seem to happen in the most homespun locations too, remote villages in remote counties, as far from the main cities as it’s possible to get.

They move to remind us that God still has the wheel and that, bad and all as things are at the moment, improvement is inevitable because an unseen but all-powerful deity is looking out for us.

So statues matter -- and not just the religious ones. For generations a landmark statute of Admiral Nelson stood in the center of Dublin like a kind of colonial acupuncture, claiming the nation for England and reminding us who was ultimately in charge of our affairs.

Admiral Nelson once stood above Dublin city on a pedestal.

The IRA blew it up in 1966, on the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Rising. That morning the then President Eamonn de Valera called The Irish Press to suggest this headline: “British Admiral Leaves Dublin By Air.” It’s impossible not to hear him laughing.

Lately, America has been rapidly catching up with this moving statues craze – and the targets have only been widening.

In the recent push for the removal of all Confederate statues, which critics rightly claim commemorate a racist system of human trafficking and slavery, the conversation behind the conversation has not occurred.

Most Americans know what these statues really represent, and they also think their forced removal represents a whitewashing of the country’s real history. They equate toppling these mustached men on horses with an erasing of the national memory.

But is it really? Isn’t there a different between remembering the past and revering it? Are these statues really reminders of the past or of the systemic institutional racism, segregation and slavery that the past was built on?

Do these national “reminders” heal a wound, or keep it raw and festering? If your ancestors owned a plantation, would you have a different understanding of the past than if your ancestors were forced in chains to work on it?

Who are these “reminders” really for then? Who do they help? What is the message they are sending to the present time? Who are they sending the message to?

We haven’t really asked ourselves this. We just say don’t erase history. We don’t really ask ourselves whom that history helps and hurts. There has been a lot of disparagement but not much debate.

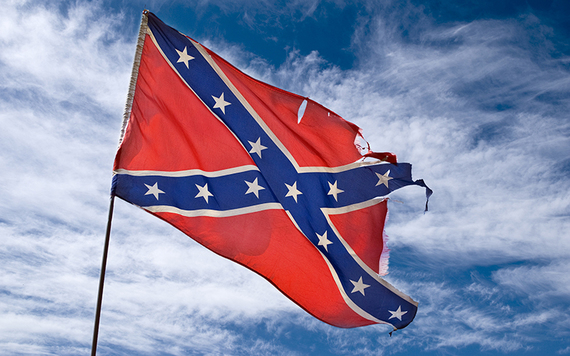

The Confederate flag, now often held high by racist groups.

It’s time we had a national conversation about the past, and about the images of the past that are embodied in statues. It’s time to have a conversation about who built America and on whose backs it was built.

It’s already happening, but it’s happening in the no man’s land between those it helped and those it hurt. As of April, at least 60 symbols of the Confederacy had been removed or renamed since 2015, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center.

How you feel about these statue removals largely depends on where you stand. Germany has no public commemorations to the Third Reich, and indeed has even outlawed citizens from reenacting its famous Nazi salute in public.

Recall that history is littered with toppled and broken statues. From Stalin to Nelson to Cromwell to Robert E. Lee, effigies of strongmen who in their time seemed undefeatable but who later fell out of favor can fall hard before or after their rule ends.

Tyrants who want to ensure their legacies are always trying to ensure their effigies are built to last. From statues to arches to coins to stadiums to tall buildings, they want to see themselves and their power carved into stone to send a message to themselves and their opponents: they mater and they are here to stay.

But where are the statues to millions of enslaved Africans who were forcibly brought here under gun and whip like livestock? Men, women and children forced to work enchained for a system that exploited and abused them from cradle to tomb?

Who is hand wringing over the “erasure” of their history? Who is even calling for it to be publicly commemorated?

Comments