"Working in mills and organizing laborers is not quite as flashy as flying IRA bombing missions and robbing museums."

This Sunday, The New York Times Sunday Styles section ran a front-page story about “Silver-Spoon Socialists,” a handful of “millennials” who are “using the riches they inherited to fight capitalism.”

Like Rachel Gelman, who said, “I was always taught that this is just the way the world is, that my family has wealth while others don’t.”

Armed with her “anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist and abolitionist” ideology -- that and millions of dollars from her family’s fortune -- Gelman and others are taking on “the man,” fighting the power, and doing whatever else they feel like doing.

Read more

Which is what rich kids always get to do, isn’t it?

This calls to mind Bridget Rose Dugdale, another trust-funder in the news these days. Dugdale used her family fortune and “anti-imperialist” leanings to take part in all sorts of Irish Republican Army operations back in the 1970s.

These include brazen thefts of prized artworks from Ireland’s Russborough House, as well as an infamous helicopter mission over Tyrone, which involved dropping bombs in milk crates on a Royal Ulster Constabulary station. The bombs never exploded.

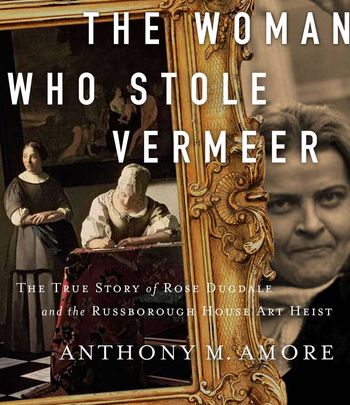

Dugdale, the subject of a new, much-discussed book entitled The Woman Who Stole Vermeer by Anthony M. Amore, was eventually sentenced to nine years in prison.

Before all that, though, Dugdale was just another (very wealthy, very English) young one trying to find her way, having put Miss Ironside’s School for Girls, then “finishing school” abroad, then Oxford behind her.

It was then that this (as Amore calls her) “reluctant debutante” decided to head off the U.S. Dugdale was still a decade from trying to bomb the Brits off the island of Ireland.

And yet, had she looked around a little bit while she was in the U.S., she could have gotten an early start on a very different kind of Irish education.

Dugdale could have learned about Anna Sullivan, the daughter of an Irish immigrant who also dedicated her life to challenging aspects of “the system.”

It was 1962 when Dugdale began studying at Mount Holyoke, “a small liberal arts women’s college in South Hadley, an ultra-liberal enclave in the western part of Massachusetts,” Amore writes, adding that the college’s founder Mary Lyon famously inspired her students to “go where no one else will go, do what no one else will do.”

What Amore doesn’t mention is that, in the grand American tradition of many idealistic thinkers, Lyon seemed to believe it was necessary to degrade some folks while you elevate others.

So Lyon’s opinion of Irish immigrants, from the town’s factory laborers to its maids, was not very high, as Mount Holyoke’s own Mary Renda, a history professor, has noted. Lyon held “derogatory views of Irish immigrant servant girls” and preferred “Anglo-Saxon New England norms.”

All the more reason Dugdale and so many other crusading Mount Holyoke students should have been paying attention to the likes of Sullivan, and the broader, vibrant Holyoke Irish American community.

As a teenager, Sullivan had gone to work at a cotton mill to help her widowed mother and younger siblings make ends meet.

The terrible working conditions Sullivan endured pushed her to organize workers, build up unions, and demand higher wages and better working conditions.

By the time Dugdale was a young, ambitious student at Mount Holyoke, Sullivan was nearing 60 and still organizing, a task made more difficult because of Holyoke’s long tradition of looking down on people exactly like Anna Sullivan.

Of course, working in mills and organizing laborers is not quite as flashy as flying IRA bombing missions and robbing museums.

But it does make the world a more just and fair place.

If those trust fund millennials can use their family fortunes to build on the work of Anna Sullivan, they may be on to something.

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

Comments