Trinity College Dublin, one of Europe's oldest universities, announced two years ago that it would engage in a process to look at historical legacy issues affecting the college.

One area looked into related to the future of human remains that were taken illegally from Inishbofin island in Co Galway and stored in Trinity.

The remains were removed by Trinity professors in 1890 for research purposes and without the consent of islanders. A decision on that was announced last week.

However, more controversially, Trinity is also considering whether a library named in honor of a 16th-century slave-owning philosopher, George Berkeley, should be renamed. A verdict on that is expected in October.

In relation to the skulls, it is clear that the academics involved in the theft knew that they were trespassing, looting, and desecrating the 14th-century cemetery. The monastery on the site, St. Coleman’s, replaced a much older one dating back to the seventh century.

Their operation took place under cover of darkness, and in a contemporary account written by one of the thieves he talks about hearing “two men slowly walking along the road and like Brer Fox we lay low and like the Tar Baby, kept on saying nothing. When the coast was clear we put our spoils in the sack and cautiously made our way back to the road.” High standards indeed.

There has been a growing campaign for Trinity to repatriate the skulls with support from such notable institutions as Notre Dame, which said in a letter that ‘’islanders today represent the most recent generation of a community of care that has venerated and safe-guarded the site of Saint Colman’s Abbey over more than 1,300 years.”

Pegi Vail, an anthropologist at New York University whose grandmother emigrated from Inishbofin, was also a prominent advocate for the return of the skulls.

Last week, the provost of Trinity apologized for keeping the skulls, saying that she was “sorry for the upset that was caused by our retaining of these remains and I thank the Inishbofin community for their advocacy and engagement with us on this issue.” At last, the remains will be buried in their rightful place.

It is taking Trinity a good deal longer to come to the “right” decision regarding George Berkeley. Not surprising really considering how much they have invested in him. Apart from naming the library after him, Trinity also has a stained glass window dedicated to him, three portraits, and various medals and awards for academic excellence in his honor.

Revered in philosophical circles, Berkeley’s primary achievement was the advancement of a theory he called "immaterialism" which held that ordinary objects are only collections of ideas, which are mind-dependent. He was also an Anglican bishop, and the city of Berkeley in California also takes his name.

But he was also a slave owner. In October 1730, while in Rhode Island, he purchased four black men to work on a 96-acre plantation he had acquired.

Similarly, he conducted religious sermons where he advocated that Christianity could be used as a means to justify the enslavement of a people, going so far as to suggest that if necessary Native Americans could be kidnapped and then educated and baptised at the college he planned to set up in Bermuda. It was part of what Berkeley said was his scheme of “converting the savage Americans to Christianity.”

There are those that try to justify what Berkeley did by claiming he was “a man of his times.”

This argument suggests that there were no voices opposing human slavery in the 1700s. However, this viewpoint has been comprehensively debunked by Dr. Phil Mullen, associate professor of Black studies at Trinity.

The truth is that there were many dissenting voices, not least from those enslaved. Berkeley chose not to listen to them and in doing so profited from his actions.

But there is another cogent reason why the library should be renamed. Berkeley was relentlessly anti-Catholic, believing Catholics were inferior to their Protestant compatriots.

In an open letter to Irish Catholic clergy, he stated, “I will venture to affirm, that neither Pope, nor cardinals, will be pleased to hear that those of their communion are distinguished above all others, by sloth, dirt, and beggary.”

His racist views were demonstrated yet again when he declared that the “Irish are wedded to dirt.”

A brilliant man with loathsome ideas and deficient moral judgment, one hopes that Trinity College consigns his reputation to the dustbin of history where it belongs.

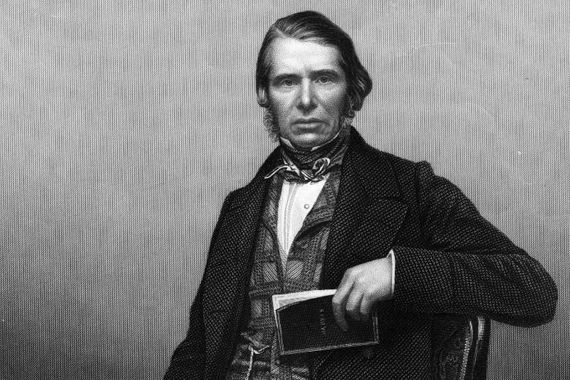

Charles Trevelyan. (Getty Images)

But it is not just institutions that are confronting their colonial and slave-owning past. The Trevelyan family which has many famous ancestors recently publicly apologized for its ownership of more than 1,000 enslaved Africans.

They are also paying reparations to the people of Grenada, where the family once owned six sugar plantations for which they received £27,000 compensation from the British government for the abolition of slavery. It was an enormous sum of money worth in the region of $20 to $27 million in today’s terms.

The family is to be commended for their actions. It came from their own initiative and was not forced upon them.

But is there a double standard at play? One of their ancestors was Charles Trevelyan, whose disastrous policies in Ireland during the Famine prolonged the suffering and undoubtedly increased the fatality rate.

Because of his role as a civil servant rather than a politician, historians disagree as to the extent of his culpability in the tragedy that unfolded. But culpable he was as under Trevelyan, relief by public works was too little too late, all food depots except on the western seaboard were closed, public works were suspended, and local relief committees were forbidden to sell food at less than prevailing prices.

He rejected criticism of the export of grain from the country on the grounds that the British government should not interfere with free trade.

He saw the Famine as a way to socially engineer the Irish population, and expressed the view that the Famine was “the judgment of God sent to teach the Irish a lesson…and the real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the Famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people.”

To many the Trevelyan family is indulging in virtue signaling with their mea culpa and the act of contrition. If they really are serious about atoning for the past mistakes of their ancestors, then they need to confront the shameful role Charles played in the Irish Famine, just as Trinity College needs to do with its beloved Berkeley and his racist views spanning two continents.

*This column first appeared in the March 1 edition of the weekly Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral. Michael O'Dowd is brothers with Niall O'Dowd, founder of the Irish Voice and IrishCentral.

Comments