Close to where I live is the village of Slane, famous for St. Patrick’s paschal fire, rock concerts, whiskey, and the birthplace of the war poet Francis Ledwidge.

In Ledwidge, we have all the contradictions and mixed sentiments associated with Ireland’s relationship with England and its army in the first half of the last century. His most famous poem is dedicated to the executed 1916 leader Thomas McDonagh.

Its opening lines are known by every young school child that has studied poetry: “He shall not hear the bittern call in the wild skies where he is lain.”

Yet Ledwidge himself, despite being an Irish language enthusiast and initially opposed to World War I, signed up to fight with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, an Irish regiment. He did so to support John Redmond’s push for Home Rule. Sadly, Ledwidge’s second tour of duty ended in his death at Ypres in Belgium.

Over 100 years on and these contradictions still abound. Perhaps one of the most contentious symbolic acts in Ireland today is the wearing of the poppy in the run-up to November 11, Armistice Day.

Associated internationally with the production of opium, at this time of year its wearing across the island is enough to produce its own toxic reaction. The poppy is a well-known and well-established emblem that carries a depth of history and complexity of meaning.

Distributed by the Royal British Legion ostensibly as a reminder of World War I and as a fundraiser for its charitable activities, it is viewed by many in this country as a show of support for the British armed forces. An army which as we have seen, at the time of World War I, contained many Irishmen, encouraged by church and state propaganda at the time to defend “Catholic Belgium.”

While the exact number of Irish soldiers who died in World War I is unclear, it is believed to be in excess of 35,000. To commemorate those who served, there are over 600 memorial sites in the 32 counties. Ranging from cenotaphs to ornate windows, the list is still not finished, with the latest project to get the go-ahead being a memorial garden in Killester in Dublin dedicated to soldiers who were rehoused there after the war.

There is no shortage of respect for fellow citizens who fought and died for a cause they believed was just, but when you add to this mix what one UK journalist in 2006 termed poppy fascism, then it becomes more volatile.

The term was initially coined in relation to the pressure put on UK TV newscasters to wear the poppy, but it has now extended to anyone in public life. In that respect, Irish people living in Britain come under pressure annually.

This year is no different as the continuing vilification of James McClean, a professional soccer player, testifies. From Derry, McClean refuses to wear a poppy. Add to that list the actor Paul Mescal from Kildare who appeared on Graham Norton’s BBC talk show on November 4 without a poppy and was immediately subjected to a barrage of criticism. Interestingly Norton himself, who is from Cork, did wear the emblem.

It’s a fact that commemorations in Ireland are problematic. Ask Charlie Flanagan who, as minister for justice, wanted to remember the contribution made to Irish history by the notorious Black and Tans, an event that was immediately branded as a betrayal of those who fought for Irish freedom in the War of Independence. He soon backtracked on that.

Discontent also surfaced with the “Necrology Wall” erected in Glasnevin Cemetery which named all the people killed in conflicts in Ireland between 1916 and 1923, including civilians, British soldiers, and IRA members. Because of continuing politically inspired vandalism, all the names were removed from the structure. This has led to a separate campaign for the construction of a national memorial to the 40 children who lost their lives in the 1916 Rising.

And let’s not forget the commemoration controversy involving President Higgins when he declined an invitation to a “Service of Reflection and Hope” organized by the main Christian churches in Ireland to reflect on 100 years of a partitioned Ireland.

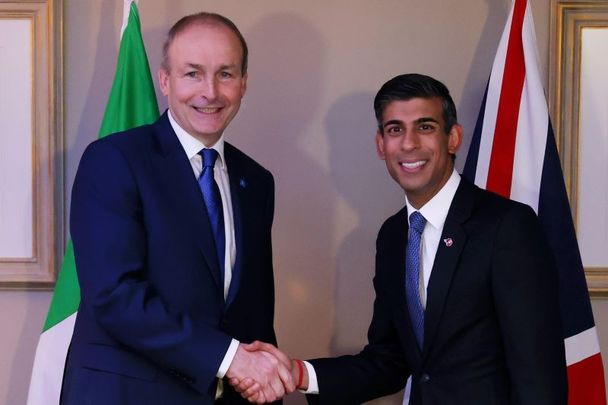

Threading on eggshells can be an easier task than trying to interpret our shared history, which is why Taoiseach Micheál Martin’s comments at the British Irish Council summit in Blackpool were tone-deaf.

Wearing a poppy, he stated that it is “appropriate ... that we would pay honor to those who lost their lives in World War II and in World War I and in other conflicts,” and that Irish people “have entered into a new mature reflection on all of these issues.”

Really? Those “other conflicts” include Northern Ireland. Should we pay honor to colleagues of Soldier F, who was guilty of pumping bullets into unarmed civilians on Bloody Sunday? How do the Ballymurphy victims’ relatives feel about honoring the British Army?

Or more recently, what about the SAS operatives in Afghanistan who, according to the BBC, repeatedly killed detainees and unarmed men in suspicious circumstances?

Martin should and does know better. His virtue signaling to a UK audience sounds sanctimonious at home where there is a complexity of feelings regarding the poppy and its symbolism.

The subliminal message of the poppy is that the British Army is a force for good, and those who have worn the uniform have always acted correctly and we should be proud of their actions. But this is patent nonsense. You cannot remember the individuals without also recalling their legacy.

The flower is also a powerful symbol of British national identity, and as such, it is not and never will be a symbol of reconciliation in Ireland. A step towards mutual understanding would be to respect the decision of those who chose to wear or not wear the poppy, which is why Martin’s comments were singularly unhelpful.

Respect for our war dead is important, which is why I attended the annual remembrance ceremony in my hometown, Drogheda, on Saturday. About 80 people took part in a respectful service for the over 300 townspeople killed in action during World War I.

It was attended by national and local representatives, Catholic, Protestant, and Presbyterian ministers, Garda Síochána, and retired members of the Defence Forces. Less than 10 percent wore a poppy despite the fact that they were on sale at the event.

Coincidently that evening while attending church, I learned that the bishop of Meath was starting a process to seek the canonization of Father Willie Doyle, a Dublin-born Jesuit priest who served as chaplain to the Royal Dublin Fusiliers during World War I.

Dubbed a martyr for charity, his courage in ministering to his men regardless of their religion was legendary. His life and death is just another rich vein in the British-Irish historical tapestry.

Doyle was killed in August 1917 just three miles away from where Ledwidge was blown up 16 days earlier. Two Irish casualties in the senseless slaughter in the mud of Ypres.

*This column first appeared in the November 16 edition of the weekly Irish Voice newspaper, sister publication to IrishCentral. Michael O'Dowd is brothers with Niall O'Dowd, founder of the Irish Voice and IrishCentral.

Comments