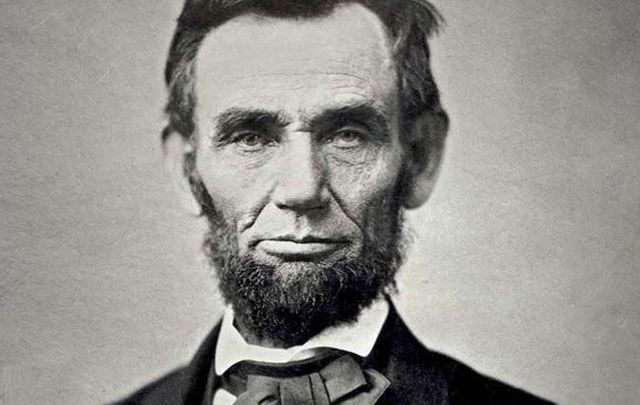

Marking Abraham Lincoln's birthday we look at how the Irish Republican Emmet influenced the US President and how the Irish situation impacted the American Civil War.

Editor's note: This following is an extract from Niall O'Dowd's newest book, "Lincoln and the Irish: The Untold Story of How the Irish Helped Abraham Lincoln Save the Union", available on Amazon.

Abraham Lincoln is known to have learned Robert Emmet’s speech from the dock by heart. Robert Emmet, just twenty-five, made the speech in 1803 after being sentenced to death for leading an abortive insurrection in Dublin. As a young man, Lincoln would often deliver it as a party piece for dignitaries visiting Perry County, where he lived.

Irish Republican Robert Emmet.

Emmet’s address was a necessary speech to learn for potential orators, but Lincoln seemed to have considered him a talisman. Knowing this years later, a political opponent won a surprising reprieve for a young Confederate spy.

In February 1865, Lincoln was considering an appeal to spare the boy when Delaware Senator Willard Saulsbury, who in January 1863 had called the president “a weak and imbecile man, the weakest that I ever knew in a high place,” appealed for clemency.

Read more: Lincoln and the Irish, the untold story revealed for the first time

Saulsbury played the Emmet card. He wrote, “You know I am no political friend of yours. You know I neither ask or expect any personal favor from you or your Administration . . . All I ask of you is to read the defense of this young man Samuel B. Davis), unassisted by Counsel, compare it with the celebrated defense of Emmet, and act as the judgment and the heart of the President of the United States should act.”

The death sentence was duly commuted.

Emmet continued as a lodestar. Lincoln also had direct contact with a member of the Emmet family. In 1856 at the Republican National Convention in New York, the chairman and keynote speaker at the convention was Robert Emmet, the patriot’s nephew and a successful politician and judge in New York. Emmet made a passionate attack on the Democrats and their embrace of slavery and may well have influenced Lincoln.

There was one other case recounted by Henry Wilson, abolitionist and later vice president under Ulysses S. Grant, who told the story of an Irish deserter that Lincoln saved. Wilson told the story in an interview with William Herndon, Lincoln's law partner, and biographer:

I remember talking early one Sabbath morning with a wounded Irish officer who came to Washington to say that a soldier who had been sentenced to be shot in a day or two for desertion had fought bravely by his side in battle. The officer said, “Told him (Lincoln) that we had come to ask him to pardon the poor soldier.”

After a few moments reflection, he said, “My officers tell me the good of the service demands the enforcement of the Law, but it makes my heart ache to have the poor boy’s shot. I will pardon him.”

Lincoln was keenly aware of world affairs despite his backwater upbringing. During the Hungarian revolution from 1847 to 1849, Congressman Lincoln, who had been elected in 1846, was one of a handful of US politicians to draft a statement in support of the Hungarian rebel Lajos Kossuth, who was seeking to break away from Austria.

The book cover for Niall O'Dowd's newest book "Lincoln and the Irish".

In the resolution, a specific reference to the Irish struggle was included. The statement was also highly critical of the British rule in Ireland, and specifically mentioned the mistreatment of two leaders of the failed 1848 Irish uprising rebels: John Mitchel, ironically, a bitter opponent of Lincoln later and a supporter of slavery who settled in the South, and William Smith O'Brien, who was transported to Tasmania.

The resolution reads:

That the sympathies of this country, and the benefits of its position, should be exerted in favor of the people of every nation struggling to be free; and whilst we meet to do honor to Kossuth and Hungary, we should not fail to pour out the tribute of our praise and approbation to the patriotic efforts of the Irish, the Germans, and the French, who have unsuccessfully fought to establish in their several governments the supremacy of the people. That there is nothing in the past history of the British government, or in its present expressed policy, to encourage the belief that she will aid, in any manner, in the delivery of continental Europe from the yoke of despotism; and that her treatment of Ireland, of O'Brien, Mitchel, and other worthy patriots, forces the conclusion that she will join her efforts to the despots of Europe in suppressing every effort of the people to establish free governments, based upon the principles of true religious and civil liberty.

He also clearly liked the Irish sense of humor and bearing. Speaking about Edward Hannegan, an Indiana senator who had been double-crossed for a position he thought he had been promised, Lincoln stated, “Hannegan had been a senator from Indiana six years, and, in that time, had done his state some credit, and gained some reputation for himself; but in the end, was undermined and superseded by a man who will never do either. He (Hannegan) was the son of an Irishman, with a bit of the brogue still lingering on his tongue; and with a very large share of that sprightliness and generous feeling, which generally characterize Irishmen who have had anything of a fair chance in the world. He was personally a great favorite with senators, and particularly so with Mr. Clayton, although of opposite politics.”

Despite Lincoln’s sympathy toward the Irish, it would be an altercation with an Irish rival—a fellow lawyer, budding politician, and remarkable leader of men in his own right—that would threaten to change the course of history years before Civil War.

Read more: The assassination of Abraham Lincoln and how two Irishmen might have prevented it

Comments