My abiding memory of Martin McGuinness is Belfast City Hall on November 30, 1995 as President Clinton and wife Hillary ascended the stage to greet the assembled thousands.

It so happened that McGuinness and I were seated close to each other and, with veteran republican Joe Cahill on the other side, I was certainly in strong Sinn Fein company.

What I remember most is Martin McGuinness’s look at the moment the president stepped on stage. His eyes were alive and bright with anticipation.

He knew as I knew that an incredible milestone had been reached with the arrival of the president and his wife.

He knew Northern Ireland, the sectarian state where he grew up and where he had later been forced to defend his people from Loyalist attacks during battles in the Bogside, would never be the same again. So good a soldier he was part of the Downing Street peace talks in 1972 aged just 22, the hardest of hard men the newspapers claimed.

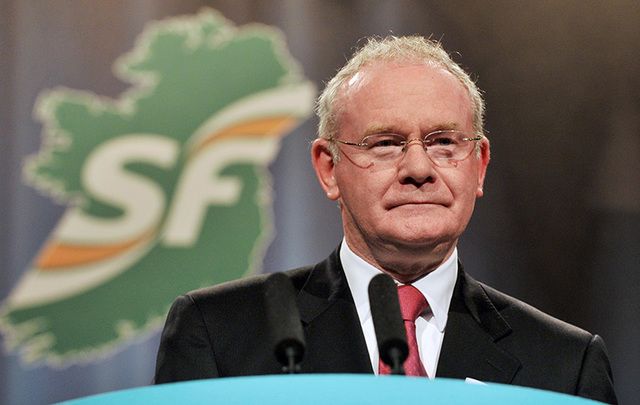

Martin McGuinness aged 22.

Now all these years later, he practically crushed my hand with his handshake and words were not necessary. America had intervened, all had changed.

I cast my mind back to a late autumn day in 1992, a few years before, as we sat in an old schoolroom in Belfast, an American delegation which first put the architecture together for an American visa for Gerry Adams and for getting Clinton to Northern Ireland. It was a long shot, but we were trying to convince Sinn Fein it could work.

The setting was slightly ridiculous, seated on school benches circa 1953. We felt like overgrown schoolboys.

McGuinness arrived and was clearly deeply agitated. He explained he had been followed all the way from Derry by security forces who had attempted to prevent him reaching the meeting. He was having none of it, he said.

When he spoke at the meeting it was with calm authority and directness. The Americans could make all the difference, he said. The British would hate more than anything to see them get involved. I remember remarking how clear-headed his thinking was. He saw the building blocks and made a calculated decision to work with our group as did Adams.

The result was the Adams visa in January 1994 that internationalized the conflict and brought America to the fore. McGuinness said the day Clinton landed he knew that was the moment the Rubicon had been crossed.

Read more: Sinn Fein likely to poll well as Northern Irish election set for March 2nd

Sure, there were setbacks, often frustrating, upsetting and annoying, but the ship was facing prow forward and inching through the turbulent waters.

McGuinness gave it his all. Barely publicized was his role in heading off a putsch by IRA quartermaster Michael McKevitt, who told an IRA general convention in Donegal in 1997 that the movement must go back to war.

He seemed to have the votes, but It was McGuinness who turned the tide and the IRA back towards the peace strategy. The peace process was saved and a year later came the Good Friday Agreement.

In 2007, after years of disputes and breakdowns, a solid power-sharing government was founded. McGuinness partnered with Ian Paisley, as unlikely a combination as chalk and cheese. I remember being at Stormont that first morning and wondering how on earth would all this work. Martin just grinned and said, “Watch us,” remarking that Paisley had as little love for British interference in the North’s affairs as he had. How right he was.

Amazingly McGuinness and Paisley made it work, as the two old arch-enemies who became known as “The Chuckle Brothers.”

"The Chuckle Brothers" Rev Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness.

McGuinness became a welcome visitor at the Paisley home. When the redoubtable reverend finally passed the family invited McGuinness to the funeral, an unheard of occurrence.

It was a tribute to his diplomatic skills. The fighter was also a superb negotiator and diplomat. Single-handedly at times, he kept the Good Friday Agreement afloat, even meeting Queen Elizabeth and dining at the royal residence in London in order to further the cause. Only McGuinness with his stellar reputation could carry that off and not incense his old comrades in arms.

Martin McGuinness shakes hands with Queen Elizabeth. Also present Peter Robinson and Prince Philip.

Throughout crises he remained the same calm McGuinness, commanding fierce loyalty from those around him. On the announcement of his retirement it was perhaps the flood of letters and tributes from Unionists that buoyed him the most and surprised many.

They should not have been. Soldier turned statesman, Martin McGuinness had excelled at both, and his extraordinary accomplishments give proof of that.

Read more: Sinn Fein’s young talent looking to future in power

Comments