Teju Cole writing in New Yorker this week about Charlie Hebdo stated it best about the forces at play in the magazine at the center of the dreadful massacre in France.

Is it a satirical magazine that should be allowed print whatever it likes or did it shade into blatant racism in recent times?

Cole wrote: ”In recent years the magazine has gone specifically for racist and Islamophobic provocations, and its numerous anti-Islam images have been inventively perverse, featuring hook-nosed Arabs, bullet-ridden Korans, variations on the theme of sodomy, and mockery of the victims of a massacre.”

“It is not always easy to see the difference between a certain witty dissent from religion and a bullyingly racist agenda, but it is necessary to try.”

It is indeed. In the 19th century, cartoons depicting the Irish as apes were very popular in Britain and the US.

One cartoonist Thomas Nast made much of his reputation displaying the Irish as gross simian caricatures in Harper’s Weekly and urging that immigrants from Ireland be sent back home.

In one infamous cartoon, he portrayed Catholic Church bishops as crocodiles landing on shore ready to devour children in America.

Nast made clear his racist views of the Irish by depicting them as violent drunks and sub human. He used the Irish as a symbol of everything wrong with America.

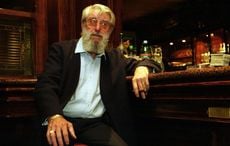

Thomas Nast

Despite his racism his reputation has survived and he is known these days in cartooning circles as “The Father of the American Cartoon.”

The racist cartoon campaign against the Irish was used even more heavily against Blacks, portraying them as tree dwelling, monkeys, lazy, shiftless, often drunk.

Before he was the beloved Dr. Seuss, Theodor Seuss Geisel thrived on anti-Black, anti-Arab, anti-Japanese stereotype cartoons. He too survived as a major beloved figure.

Theodor Seuss Geisel. University of California, San Diego, Library

So the history is very clear. Satire can quickly turn to hate speech. It can often depend on who is doing the drawing and the historical context.

So where is this line between hate speech and satire, or is there one?

I think there is, and Nast and Dr. Seuss clearly crossed it.

Thomas Nast

The images of Nast and Dr. Seuss are now widely seen as wrong, abhorrent, offensive. What are we to make then of Charlie Hebdo, the magazine which gladly published such stereotypes of shifty Jews, gay Muslims with Muhammad in one cartoon naked with only a star covering his rear.

Charlie Hebdo was always controversial in a juvenile delinquent way but it was far more serious than that.

In 2011 the French government begged them not to publish a naked likeness of Muhammad. As the New Yorker reported at the time:

When word got out a week ago Monday that the paper was printing a representation of Muhammad—an act that many Muslims consider blasphemous—Paris police called the editor (and cover cartoonist), Stéphane Charbonnier, just as the issue was closing. Charb, as he is known, sent the prefecture the front and back covers, and the police urged him to think again. He declined—satire is, after all, his bread and butter—and the issue hit newsstands a week ago Wednesday.

Immediately, the French government increased security and announced its decision to close the twenty foreign outposts last Friday, which was a Muslim day of prayer. French Prime Minister Jean-Marc Ayrault issued a statement criticizing the cartoons and any such "excess." Politicians and editorial pages in much of France attacked the drawings as irresponsible, inopportune, and imbecilic.

In 2012, the White House criticized the magazine for portraying Muhammad in such a negative light saying the images would be "deeply offensive to many and have the potential to be inflammatory."

Of course the newspaper argued otherwise, that intellectually they were making the point by satire. That the cartoons were an attack on extremist ideology, not an entire religion.

But I’m sure to many Muslims in the French ghettos what they were doing was deeply offensive, the Nast-type all white characters on the rich side of town looking down and condemning them and their God.

2011 Charlie Hebdo cover. Reads: “100 lashes if you don’t die of laughter!”

Tom Spurgeon editor of The Comics Reporter told The New York Times that the dreadful events have started “a dialogue about what privilege means, and a feeling that you don’t need to insult people, especially downtrodden people, to make your points.”

We can defend free speech without agreeing with it. But where does free speech degenerate into hate speech, and do we defend that?

Obviously the massacre of the Charlie Hebdo workers was horrific and completely insane, but in defending free speech we don't have to agree with what was bordering on hate speech to many.

Our much maligned Irish emigrant ancestors would likely agree. They would see a line from Nast to Charlie Hebdo and would view it all as much more than a bit of fun and satire.

Alas, it is too late for so many, including that incredibly brave Muslim policeman who died, shot like a dog, defending folks who were ridiculing his religion.

And while the French say they are all Charlie Hebdo now the great fear is they will be Marine Le Pen, the leader of the semi-fascist party in the next election, making matters even worse.

Comments