The following is an extract from Niall O'Dowd's newest book "George Washington and the Irish: Incredible Stories of the Irish Spies, Soldiers, and Workers Who Helped Free America". This week (until June 26) the Kindle edition is available via BookBub for just $1.99.

“May the generous Sons of Saint Patrick expel all the venomous reptiles of Britain.”

- George Washington, June 1776, drinking a toast to the Irish as reported by The New York Gazette and The New-York Packet newspapers.

George Washington was all in on the Irish struggle for freedom.

As the Mount Vernon Historical record notes:

“General Washington, and the larger American population, was fascinated by the mounting political unrest in Ireland… Ireland’s patriotic struggle against the British crown mirrored their own hunger for liberty.”

Washington’s warm feelings for the Irish and the influence of the Irish fight for independence showed themselves in several ways.

He clearly believed his own words that the Irish had a “firm adherence… to the glorious cause in which we are embarked.”

Read more

He did not have to look hard for evidence of that.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the Sons of Saint Patrick’s toast was a clever call.

“Generals born in Ireland or who had Irish parents commanded seven of the 11 brigades wintering in Morristown,” the magazine notes. A figure that makes entirely clear how important Irish leaders and men were in the vanguard.

What also drew Washington to the Irish was the fact that in Ireland there was enormous support for the Americans fighting the same hated British for their freedom.

The Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, from 1776 to 1780, John Hobart, Earl of Buckinghamshire, wrote that the Irish Presbyterians were “in their hearts Americans” and they were “talking in all companies in such a way that if they are not rebels, it is hard to find a name for them.”

~~~~~~

Two separate Saint Patrick’s Day events, in 1778 and 1779, also make Washington’s feelings clear. In the vast encampment at Valley Forge, in the winter of 1777 and the spring of 1778, the 11,000 soldiers of the Continental Army under George Washington suffered great deprivation as did the 500 domestic women camp followers.

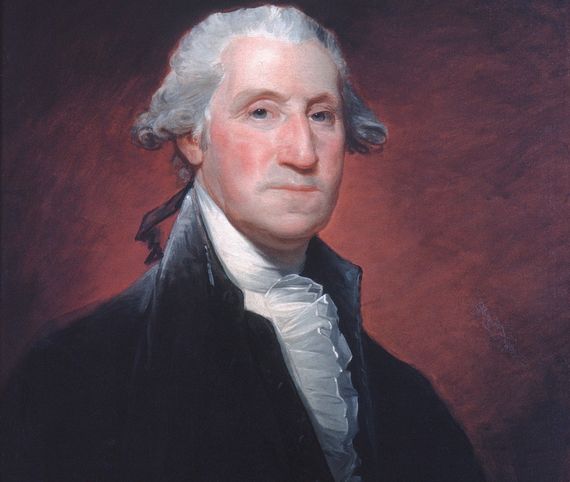

Washington at Valley Forge–December 1777–8.

It was not so much from the weather, which had none of the savagery that the winter of 1778 would have, but the fact that so many were ill-clad, without shoes and there were constant interruptions in the food supply. Men were surly, quick to see insult, and fearful of what lay ahead. There were rumors of mutiny, as there would be again.

If an army marches on its stomach, as Napoleon claimed, then Washington’s men had empty bellies and were in dire danger of taking Napoleon’s edict to the extreme. Food was a constant source of anxiety and fretfulness.

As Saint Patrick’s Day, March 17th, approached, the tensions between different ethnic groups within Washington’s army rose like the spring tides.

The Pennsylvania Germans, in particular, loved to ruffle the Irish battalions. Germany had sent the most participants of any European group, outside the British and Irish, into battle during the Revolutionary War.

German soldiers served in equal numbers in both armies, while there were many Germans associated with pacifism rather than fighting.

That dislike of battle did not extend to members of Washington’s German battalions. The Germans were quite frequently recruited into what would now be known as the military police.

As such, they were often the guards and captors of soldiers who had broken the law in some way, either through drinking, scuffling or more serious deeds. The Irish, with their love of carousing, were obvious offenders.

The Germans were known as rough jailers. They also stood apart as very few Germans knew the English language, which almost all of the army spoke. This led to numerous misunderstandings and conflicts.

There was bad blood from the beginning with Washington’s Irish battalions, likely due to German hostility to the rule-bending Irish. On one infamous occasion, it almost spilled over into an all-out battle.

Read more

As remembered by Colonel Allan McLane of the Continental Army, Washington himself had to get personally involved to resolve the matter. McLane wrote the following account in the wake of the incident, the text of which is contained in the annals of the Pennsylvania Historical Society.

“When Washington and his army lay at Valley Forge in 1778 some of the Pennsylvania Germans made a Paddy and displayed it on Saint Patrick’s Day to the great indignation of the Irish in the camp.” (A scarecrow covered with flecks of green cloth and a bishop’s miter on its head. Basically, it’s a Protestant insult to St. Patrick and the Irish.)

“They [the Irish] assembled in large bodies under arms, swearing for vengeance against the New England troops saying they had got up [created] the insult. The affair threatened [to become] a very serious issue; none of the officers could appease them.”

“At this, Washington, having ascertained the entire innocence [according to themselves] of the [German] troops rode up to the Irish and kindly and feelingly argued with them, and then requested the Irish to show the offenders and he would see them punished.

“They could not designate anyone. ‘Well,’ said Washington, with great promptness, ‘I too am a great lover of Saint Patrick’s Day, and must settle the affair by making all the army celebrate the day.’

“He, therefore, ordered extra drink to every man of his command and thus all made merry and were good friends.”

It is clear from the account that Washington sided with the Irish and called for a party in their honor.

A year later, it was very different. The camp was at Morristown, New Jersey, not far from Valley Forge and it was a cold coming that greeted the Continental Army when they took to their winter quarters.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

~~~~~

Twenty-eight separate snowstorms raged down on the shivering army between November 1779 and April 1780. Snow drifts of six feet were common. It was the coldest winter ever measured up to that time.

It was the cruelest time of the American Revolution. Men froze to death while others crowded together for warmth and survival. Food was scarce and disease rampant. The dreaded smallpox made its appearance, thankfully stymied by vaccines. But it still left many men weak and ailing. It was the ultimate winter of discontent. There was renewed talk of mutiny.

How bad was it at Morristown? “We were absolutely, literally starved,” Private Joseph Plumb Martin recalled after the war.

“I do solemnly declare that I did not put a single morsel of victuals into my mouth for four days and as many nights, except a little black birch bark which I gnawed off a stick of wood, if that can be called victuals. I saw several of the men roast their old shoes and eat them, and I was afterward informed by one of the officers’ waiters, that some of the officers killed and ate a favorite little dog that belonged to one of them.”

By March, the storms and the snow drifts had not let up or disappeared. Washington sought for a way to keep morale up. He decided to give his entire army a day off, on Saint Patrick’s Day, March 17th.

It was a testament to thousands of Irish who fought for him that Washington decided Saint Patrick's Day would be the only day of the year to offer his men a surcease and bring some lightness of spirit amid the encircling gloom.

As for his part, Washington was captivated by the Irish struggle being fought by the United Irishmen with the same ideals and vision that Washington had of true freedoms for all.

Read more

So it was no surprise that Washington decided that Saint Patrick's Day 1780 would be a day of rest and revelry -- an occasion to express solidarity with the “brave and generous” people of Ireland.

Washington issued the following proclamation: “The General directs that all fatigue and working parties cease for tomorrow the SEVENTEENTH instant,” read the orders, “a day held in particular regard by the people of [Ireland].”

Washington also asked “that the celebration of the day will not be attended with the least rioting or disorder.”

Washington himself personally celebrated. The New Jersey Journal, in its issue of March 15, 1780, published an account of a dinner in the camp at Morristown the day before:

“An elegant collation [meal] was provided by the officers of Colonel Jackson’s regiment” which Washington and several of his staff attended. Thirteen toasts were drunk, among them “St Patrick: “The Volunteer of Ireland: “May the cannons of Ireland bellow until the nation be free,” as well as toasts to the Irish leaders at the time who had won their own parliament (The Act of Union dissolved it in 1800): Henry Grattan, and the Duke of Leinster.

The New York Gazette reports that “next morning was ushered in with music and the hoisting of colors exhibiting the 13 stripes, the favorite harp and an inscription reading in capitals ‘The Independence of Ireland’.”

Washington issued a further proclamation about Ireland on March 16: “The General congratulates the army and the very interesting proceedings of the parliament and the inhabitants of the country which have lately been communicated not only as they appear calculated to remove those heavy and tyrannical oppression … but to restore to a brave and generous people their ancient rights and freedoms.”

George Washington.

As a shrewd commander, Washington knew that paying tribute to the fight for Irish freedom would play very well with his Irish troops. Luke Gardner, a member of the Irish parliament, stated in the Irish House of Commons in 1784 that he had been told “it was a common practice for the soldiers of the Pennsylvania line to converse in the Irish language.”

Light-Horse Harry Lee, father of Confederate general Robert E. Lee, wrote in his memoir about the Pennsylvania battalion: “They were known by the designation of The Line of Pennsylvania but they should have been called the ‘Line of Ireland.’”

Lee the senior was especially close to Washington, eulogizing him when he died as “first in war, first in peace and first in the hearts of his countrymen.” No doubt his respect for the Irish was shared by Washington.

In a biography of Commodore John Barry, the Irish-born founder of the American navy, author Joseph Gurn highlights how dear Ireland remained to Barry and all Irish fighting in the Revolutionary War and recounts the following story from an officer.

“While the army lay at Valley Forge in December 1776, Major Forest, in compliance with a regular order, marched the officers of his Irish regiment to take the oath to defend and support the independence of the United States.

“An Irish officer stepping forward exclaimed ‘Before we go in could you not, major, contrive to see the general and prevail upon him to put little Ireland in the oath?’

“‘That we could never do,’ replied the major, ‘but while we are engaged with England on the one side, let Ireland seize the golden opportunity and assail her on the other. Now is the time.’”

Read more

Washington was completely aware of the drive for freedom in Ireland.

As for the number of Irish in Washington’s army, the redoubtable Irish American historian Michael O’Brien in his 1937 book, George Washington's Associations with the Irish, counted more than 10,000 Irish names among the enlistment rolls kept in Washington of recruits to the Continental Army across the full period of the war.

(It should be noted that St Patrick’s Day was celebrated rather differently among the Irish fighting for the British. As the Journal of The Friendly Sons of Saint Patrick noted: “‘Volunteers of Ireland’, enlisted on the royal side of the dispute, [sat] down 400 strong on March 17, 1779, to a banquet in the Bowery where the King, no doubt, was toasted while the ‘shamrock was drowned.’ These Volunteers a year later were deserting to the patriots in such numbers that Lord Rawdon was offering ‘10 guineas for the head of any deserter.’” It was obvious where Irish sympathies lay, even at the heart of the British Army.)

* Niall O'Dowd's newest book "George Washington and the Irish: Incredible Stories of the Irish Spies, Soldiers, and Workers Who Helped Free America" is available on Amazon here. This week (until June 26) the Kindle edition is available via BookBub for just $1.99.

Looking for Irish book recommendations or to meet with others who share your love for Irish literature? Join IrishCentral’s Book Club on Facebook and enjoy our book-loving community.

Comments