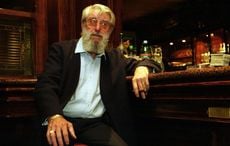

| Northern Ireland Attorney General John Larkin. |

The Northern Ireland Attorney General John Larkin told an inconvenient truth when he stated that inquiries into crimes committed before the 1998 Good Friday Agreement should be discontinued.

He is correct. Northern Ireland needs to draw the line under the past and get on with the future.

That is a hard truth for people on both sides, especially victims, to swallow, but better tell the truth than wallow in an everlasting land of false promises when it comes to actually carrying out such inquiries.

The people of Northern Ireland have proven remarkably resilient in their ability to move on – look at Martin McGuinness and Peter Robinson sharing power for instance.

Larkin was only stating the obvious. He pointed out that prosecutions following such inquiries, given the time that has passed and the human fallibility involved in terms of memories and health, would be next to impossible.

What he did not mention was that many of the inquiries, such as the Patrick Finucane murder and the Dublin/Monaghan bombings, have been utterly stymied by a refusal by authorities to grant access to the most relevant information.

Such crimes will likely never be prosecuted at this stage as the evidence has been withheld. The Unionist community no doubt have longed for similar inquiries into wrongs they suffered. There is no shortage of victims anywhere.

All the more reason then, that after a gap of at least 16 years and much longer in many cases, the truth must finally be told that such inquiries are no longer possible.

The just-released Smithwick inquiry in the Irish Republic into police collusion in the deaths of two senior RUC policemen, killings that occurred in 1989, is a case in point.

It found there was significant evidence of collusion, but could take the findings no further.

Such is the reality of what happens with the passage of time and the failure to have access to vital contemporary records and interviews.

Many cite the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission as an example of what can be achieved to right old wrongs.

But one could also cite Rwanda, where a genocidal civil war between Hutu and Tutsi tribes ended in reconciliation, not in terms of investigating wrong done but in creating democratic structures that led the country to peace.

The level of condemnation of Larkin’s comments from all sides makes it clear he was telling an inconvenient truth. The stark reality is that the passage of time has forever dimmed hopes of fully examining crimes and prosecuting those responsible.

Those are the facts, and Larkin deserves praise not condemnation for so saying.

It also has the additional benefit of allowing Northern Ireland to begin building a civil society based on equality and reconciliation without any untruths uttered to those who suffered the most.

Comments