Editor's note: The following is an excerpt from "A New Ireland" (Skyhorse Publishing) by Niall O'Dowd, founder of IrishCentral. This is the second article following on from "The tragedy behind how abortion became legal in Ireland."

The referendum battle begins

Following the death of Savita, the call for a referendum to legalize abortion increased dramatically. The horrible faith of the smiling young Indian woman was discussed everywhere. Nonetheless, it was no sure thing. Taoiseach Enda Kenny felt clarity was the key to the successful passage of the amendment.

“There needs to be a real discussion here, and people would want to know if you’re going to take that (The 8th Amendment) out of the Constitution, what are you going to replace it with?” he asked.

He and his successor Leo Varadkar who took over in 2017 felt the strategy had to be just right. Same-sex marriage between two consenting adults was an easier sell than introducing abortion into what recently had been the most conservative country in the Western hemisphere. The fact was that abortion was an incredibly difficult issue on both sides.

Kenny knew the intricacies and warned his cabinet at the first meeting on the topic that If a referendum were to be held right now, “it would not be passed.”

But Kenny’s hunch was also that after Savita and Miss X and Miss Y the country was ahead of the political class if the right tactics and message were utilized. Support had to come from the ground up, which is why, in the first instance, the imprimatur of the Constitutional Convention was vital.

Former Irish leader Enda Kenny.

His instinct was right. The Constitutional Convention was convened. The Irish Times reported that “Ninety-nine men and women gathered over five weekends in Malahide, Co Dublin, and heard from 40 experts in medicine, law, and ethics and six women directly affected by the amendment.” (The 100th person was the chairman, a distinguished judge, Mary Laffoy.)

The delegates would acquire incredible knowledge and an “almost uniquely comprehensive understanding” of abortion, Laffoy stated.

Given that, the result of their deliberations was astonishing: an extraordinary 87.3 percent wanted the amendment removed from the Irish constitution and 64 percent wanted no restrictions on abortions in the first twelve weeks of pregnancy.

The outcome was far more liberal than anyone had expected. It also showed the inability of the Catholic Church and its acolytes, such as the Knights of Columbus, to muster its base in opposition on arguably the most important issue of all to them.

From the convention, the recommendations went to The Oireachtas Committee dealing with constitutional referendums.

They met and backed up the citizen’s Constitutional Convention vote.

The Times reported that: “Led by Fine Gael Senator Catherine Noone, it would eventually mirror the decision of those 99 citizens, with the majority of TDs and Senators voting in favor of unrestricted abortion up to 12 weeks, and for access to terminations in the case of fatal fetal abnormality or where the life or health of the mother was at risk.”

The committee concluded its work in December 2017. Leo Varadkar had replaced Kenny as Taoiseach in June of that year. The last great battle between secular and religious forces in Ireland was now set. Varadkar just needed to announce the date. It was game on.

The old Ireland is gone

“I grew up in an Ireland that was so different. It’s not just another country it’s another planet,” - Ailbhe Smyth, Repeal the 8th Amendment Leadership Member, on the referendum result.

The path to the referendum date had not been all smooth.

Debate in the national parliament on the abortion referendum was fraught as conservative members attacked the proposed referendum bill. Health Minister Simon Harris led the debate for the government.

“I hope that as a country we can no longer tolerate a law which denies care and understanding to women who are our friends, our sisters, our mothers, our daughters, our wives.”

Hildegarde Naughton of Fine Gael, previously against removing the 8th, changed her mind after being educated about the abortion pill being allegedly effective for ten weeks.” Abortion pills are being taken in Ireland and if we do nothing, some women in the not-too-distant future will rupture their uteruses and die,” she said.

There was one sensational development. Micheál Martin, leader of the main opposition party Fianna Fáil, announced he was in favor of abortion up to 12 weeks. His own party at their annual convention had voted 3-1 against repealing the amendment.

He stated: “While I have supported different proposals to clarify the law and to address the threat to the life of the mother I have been broadly in favor of the law as enabled by the 8th Amendment.”

His decision was also influenced by the easy availability of the abortion pill. “Equally it is clear that the reality of the abortion pill means we are no longer talking about a procedure which involves the broader medical system.” However,” he added, “I believe we each have a duty to be willing to question our own views, to be open to different perspectives, and to respond to new information…I will vote accordingly.”

This admission of support from the leader of the party founded by Éamon de Valera, whose constitutional ban on abortion was being ripped asunder, was a huge boost for the Yes side. The unseen factor was the abortion pill importance. Irish women were using it and it was apparently effective up to 12 weeks. So why should the much safer type of abortion, with medical assistance, not be approved?

Ailbhe Smyth, Repeal the 8th Amendment Leadership Member, on the referendum result.

Leo Varadkar announced that the referendum would be held on May 25, 2018. Ireland “already has abortion, but it is unsafe,” he said. “Women from every county are risking their lives” by obtaining abortion tablets through “the post.”

The 1983 abortion referendum was one of the nastiest political campaigns in Irish history, but the 2018 campaign was conducted with far more restraint. Perhaps it was out of respect for the memory of Savita, whose face appeared on Yes posters throughout the last few weeks of the campaign. As Irish Times writer Harry McGee noted:

“The Savita case was never too far away from people’s minds during the eight weeks.”

Ivana Bacik, a Labour Party senator and women’s rights activist, also pointed to Savita’s death as a major factor.

Writing in the Guardian, she stated that the reaction to the Savita and Miss X case meant that “public opinion had thus shifted towards supporting repeal of the constitutional ban and for legal abortion to take place in Ireland.”

Maureen Dowd, star columnist of The New York Times, who was in Dublin to cover the story, wrote: “This country is in the midst of an excruciating existential battle over whether it should keep its adamantine abortion statute, giving an unborn baby equal rights with the mother. Under the Eighth Amendment, abortions are illegal, even in cases of rape or incest. The only exception is when it is believed that the mother will die. Anyone caught buying pills online to induce a miscarriage faces up to 14 years in prison.”

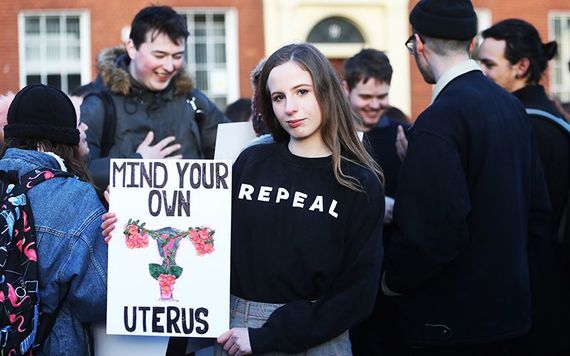

Repeal celebrations in Dublin.

Archbishop Eamon Martin, Primate of Ireland, issued a plea not to remove the 8th from the constitution.

“When you go inside the voting booth on 25 May, pause and think of two lives—the life of the mother and the life of her baby—two hearts beating; two lives which are both precious and deserving of compassion and protection,” Martin said.

He went on: “The Eighth Amendment recognizes the equality of life of a mother and her unborn baby,” and said women’s lives “are precious, to be loved, valued, and protected.”

But he said babies’ lives are also “precious, to be loved, valued, and protected.”

Martin also said abortion was not a Catholic issue, but one of human dignity steeped in “reason as well as in faith,” and is a value for “people of all faiths and none.”

The Pro-life Campaign issued its own statement headlined “Life Equality, Keep the 8th.”

“Each human being regardless of age, gender, disability, race, status in society, possesses a profound, inherent, equal and irreplaceable value and dignity.

"Abortion advocates want the unborn child to be an exception to this rule. To do this they resort to the ploy of denying the humanity of the unborn.

"The sign of a truly civilised society, however, is one that welcomes everyone in life and protects everyone in its laws.

"Equality includes Everyone."

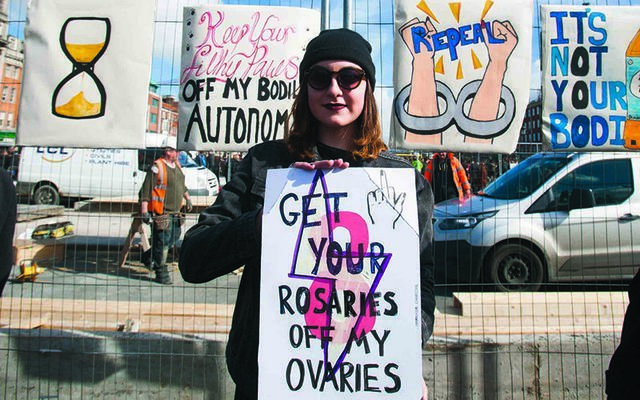

"Repeal the 8th"

As noted, the church went quiet as the debate heated up. The topic of abortion should have been catnip to them, but as the Jesuit magazine America noted:

“A notably muted voice during the debate… has been that of the Catholic Church in Ireland…its moral authority weakened by years of revelations about the sexual abuse of children by its clergy, the Irish Church, many say, has taken a low-profile role on the vote.”

The lack of a vigorous church response certainly impacted the campaign. Yet the Church was like Banquo’s ghost at Macbeth’s coronation banquet: with the sins of the past still resonating in the public mind.

The abortion campaign was also heavily influenced by a scandal involving Irish women getting false all clears from pap smears conducted by a company in Texas, which had been employed by the Irish health service, on the grounds of saving money. Many women would subsequently die because of these horrifying misreads.

Many Irish female voters perceived this as another example of neglect of women’s issues by the government.

On the pro-life side, two arguments were being made: The first that a provision allowing abortion, in the case of a risk of a mother’s suicide, meant the abortion could happen up to six months; the second that the vast majority of Down Syndrome babies were being aborted in Britain. The Yes answer was there was no way to identify a Downs baby in the first twelve weeks—a claim the No side denied.

However, when it came to expert testimony on the overall issue, there was far more buy-in on the repeal side by doctors and surgeons. This became particularly important during the televised debates when complex issues around abortion were examined.

There were also the lessons learned from the same-sex marriage victory: personal stories worked, they worked especially on social media, and they worked when shared with close friends and families. Tales of incest, rape, pedophile attacks, and taking night boats and trains to London for abortions all came spilling out.

Following the vote, 40 percent who voted “yes” said their vote had been influenced by personal contact with a woman or women who shared their stories with them.

As the voting day approached, the interest from the world media was beyond belief and the global press descended on Ireland.

Would Ireland once again defy its own history and rigid Catholic past to allow abortion?

As the Irish Times noted: “This extraordinary referendum campaign seeped into Irish public consciousness on doorsteps, in the streets, in the media, or on the airwaves… right up to polling day.”

The overall result was too close to call. The general sense was there would be a Dublin/rural split with the more conservative country voters disapproving. There was a large undecided vote.

The final opinion polls showed the gap closing with the repeal group ahead but there was widespread speculation of “shy” No voters not admitting they would vote against repeal.

Then came the moment of truth.

On May 25, 2018, the Irish voters spoke loudly and vociferously and they voted for abortion up to twelve weeks with no restrictions. 66 percent voted for, 34 percent against.

Even the most optimistic repeal advocates had not dared to dream of such a big win.

The Taoiseach Leo Varadkar welcomed the result.

“What we have seen today is the culmination of a quiet revolution [that has been taking place] for the past 10 or 20 years.” Still, it was a bittersweet victory.

Savita Halappanavar’s father full of emotion, told the Observer newspaper “I have no words to express my gratitude to the people of Ireland.”

“I’m really overwhelmed and proud,” Dominique McMullan, 31, told the Guardian while wiping away tears. “With the marriage equality referendum and this, we are leading the way—we are a new country. The old Ireland is gone.”

The Guardian headline read: “Ireland votes by landslide to legalize abortion.”

Every constituency bar Donegal voted to repeal. There was no city/rural divide.

In Dublin, a large mural of Savita Halapannavar became a symbolic pilgrimage site with hundreds leaving notes and candles.

Dominque McMullan had made her way there, too.

“I came down especially to pay tribute,” McMullan said. “It’s brilliant that this has happened, but we can’t forget the people who died because of our laws.”

W. B. Yeats’ words “All changed, changed utterly” spring to mind.

A new generation had changed Ireland, from a hidebound narrow and insular country to one of the most liberal and admired in the world. This was the reality that would greet Pope Francis during his August visit. Between two popes, John Paul II and Francis and their visits to Ireland 40 years apart, the country had changed beyond all recognition.

Just three months earlier abortion had been legalized by a stunning referendum win of 66 percent to 34 percent. In 2015 same-sex marriage had also been passed by a similar margin.

Comments