Noreen Bowden has worked on Irish emigrant issues for 20 years and headed up the Irish Emigrant Advice Network at one point for several years .

She understands better than most the ambivalence in Ireland towards emigrants and those who leave the country.

She has just written a thought provoking piece for

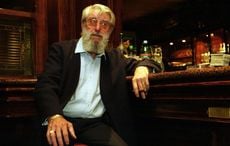

Partly it was brought up by my brief run for Irish president where the Irish Times op ed page and several other newspapers questioned whether I had the right to run as an American and Irish dual citizen.

Bowden writes that all is fine as long as emigrants and the Diaspora are sending back money and helping with investment but becoming part of the system or having actual input is not a part of the bargain as far as the Irish are concerned.

She states "When times are tough,... we hear the calls to embrace our renewed status as an emigrant nation. The loudest of these voices tend to belong to those who feel no urge to move themselves’

She notes that "In the 1980s, Brian Lenihan Snr’s “We can’t all live on a small island” seemed to sum up governmental complacency. During the current crisis, it was former Tánaiste Mary Coughlan who highlighted the government’s non-response to rising emigration figures: she claimed young people were emigrating because “they want to enjoy themselves. That’s what young people are entitled to do.”

She is making a point I fully understand.

Talk of emigration being good neatly sidesteps involuntary emigration which is a critical issue right now in Ireland,It is fine for those who want to go abroad, but what about the 50 per cent of young people who are afraid they will have to emigrate just to get a job?

Bowden points out that the Irish leaders like to have their cake and eat it too when it comes to emigrants and the Diaspora.

She writes; "It may have been Mary Robinson who started the celebration of the diaspora in Ireland in the 1990s, but her embrace was soon followed by the phenomenon of diaspora engagement for economic purposes. Irish policy-makers realised we were on to something."

She notes that "The Irish establishment has responded enthusiastically. Former Taoiseach Brian Cowen eagerly talked up the diaspora as a “huge and willing resource” when he launched the Smart Economy strategy in 2010. Enda Kenny was thinking similarly when he announced the initiative in which diaspora members would be paid for job creation. During the crisis, the notion that the diaspora could save us from our financial fate has loomed large. There seems to be no limit to what we can ask of our loyal foot soldiers abroad."

However, Bowden points out that when it came to having an emigrant possibly running for president it became a very different take.

The mentality among some was that ‘He’s not one of us’ she writes.

"There were plenty of voices pointing out that O’Dowd isn’t really one of us any more.

She notes that "The Irish Times ran an unintentionally comical article from the Northern Ireland-born, New York-resident Walter Ellis, who plaintively opined that O’Dowd “would not get my vote”. No surprise there, as Ellis is as disenfranchised as O’Dowd. Irish Times editors thoughtfully appended to the article the text of the US oath of allegiance taken by immigrants when they became US citizens. They did not add that the Irish government does not recognise such oaths as a renunciation of Irish citizenship."

Bowden concludes that " Once you go, your money, your contacts, and your expertise are welcome. Your presence in the political system is not."

That is an interesting finding and one that will hit home with emigrants everywhere. It will be interesting to see how it plays out.

Comments