Denis Kelleher was one of those who “came from away” and spent one week in Newfoundland after their plane was forced to land on the lonely Canadian outpost after news of 9/11 forced America to shut down air travel.

Denis was one of the most successful Irishmen ever to set foot in America. From near Killarney in Co Kerry, Ireland, he emigrated at a young age but unlike so many who went into construction or the bar trade, he started off as a messenger on Wall Street.

He proved to be a brilliant financial expert and soon was forming his own companies. He built an incredibly successful discount brokerage firm called Wall Street Access but distinguished himself as much in the area of philanthropy as making millions.

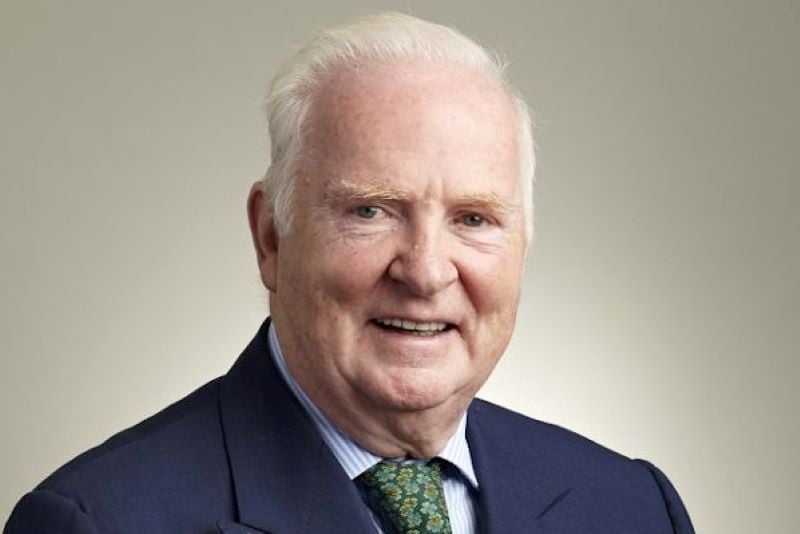

The late Denis Kelleher.

Now, on September 11, 2001, he was returning to the US from Italy, from the Isle of Capri where he, his wife Carol, son Sean, and Sean’s wife Wendy, had attended the wedding of a member of the powerful Newhouse family. Sy Newhouse, owner of Condé Nast, the parent company of Vanity Fair among other publications, was a close friend.

Kelleher and his family were seated in the first-class section of the Delta Airlines flight due into New York from Rome at 3:00 pm New York time. It had been an uneventful flight, and he was looking forward to getting back and seeing his three grandchildren again.

Suddenly, in late morning, as they approached the Canadian coast, they noticed the plane dropping sharply in altitude and commencing a sharp descent pattern.

The disquiet among the other passengers was evident to Kelleher, who initially thought there was a mechanical problem with the plane. He was thus quite relieved when the captain came on to advise that there was nothing wrong with the plane, but that they had just been advised by the Federal Aviation Administration that they should land right away. He said he would give more information when the plane landed.

There was a discernible buzz among the passengers in the plane, who were wondering what had caused the FAA to issue such a ruling. Perhaps Kennedy Airport and indeed the whole East Coast was closed by fog, or there had been some kind of aviation accident, some passengers surmised.

Shortly after landing at St. John’s Airport, in the capital of Newfoundland, the captain came back with an extraordinary message: “Now I can advise you that America has been invaded,” he told the startled passengers. He told them that the World Trade Center had been destroyed, the Pentagon had been attacked, and that there were several other landmarks under fire. He told them he was too emotional to discuss it any further with them but that he would find out more information on the ground and get back to them. He said no one could leave the airplane under any circumstances.

Kelleher thought he was in the middle of a bad dream. “It just seemed so absurd, insane actually,” he says.

“How could the World Trade Center be destroyed? It was impossible, the most outlandish thing I had ever heard. And who had invaded us?

"I immediately thought of a nuclear missile or something like that. Everyone on board was frantic trying to find out what happened."

His son Sean came racing over. “Dad, that’s where Alex works,” he said, referring to Alex Steinman, a close friend of the family. Steinman was employed in Cantor Fitzgerald, high in the north tower of the WTC.

Kelleher immediately reached for his phone. It turned out that he had the only working phone on the plane. It was a special international model that allowed him to call from or to anywhere in the world. Now, as frantic passengers crowded around, he tried to reach people in New York.

Impossible. All the lines were dead, and it was clear that the catastrophe was having far-reaching consequences as attempted calls to other destinations failed.

Finally, in desperation, with the passengers increasingly agitated, he called a lawyer in Kansas City who had recently worked on a major deal for him. Somehow, the phone rang and his lawyer friend, John Marvin, picked it up. It was from him that Denis, with the other passengers crowded around, learned the horrific truth of what was happening in America. Marvin told him about the plane, about the unbelievable scenes of people jumping, and of buildings being leveled to the ground.

“I had a very tough time comprehending what he was saying,” says Kelleher.

For all the passengers on board, there was an immediate sense of shock and disbelief. For the Americans on board, the major preoccupation was their families. How were they doing, especially those residents in New York?

John Marvin began calling all around the country, to relatives and friends of the passengers, relaying information when he could get it back to the plane. Denis found out that his son and daughter and in-laws and grandchildren were all safe. It was a tremendous moment of relief, he remembers.

Due to his company’s proximity to the World Trade Center, he was also desperately worried about his employees and friends on Wall Street. However, he was unable to immediately contact them. When he did, he found out that his son’s friend Alex had called his wife a number of times and told her that they were evacuating. They now had hopes that he had survived.

His own workforce had had a narrow escape. Back in Kelleher’s in New York, on the morning of September 11, his secretary Mary Schaffer had decided to come to work early because she knew her boss was returning from his overseas trip and would want to make immediate contact. As a result, she went through the World Trade Center earlier than usual, which may well have saved her life.

When the news of the first plane hitting came over, she gathered in Denis’s office with some senior executives. Suddenly, they heard what proved to be the second plane, coming in overhead, with an ear-splitting roar. It passed right beside them, veering sharply as it sought to hit the tower head-on. They all instinctively ducked, and soon after, the order to evacuate was given.

Back on the plane, having made his own calls, Kelleher’s phone was getting handed around to all the news-starved passengers. Each, in turn, called loved ones, or anyone else if they could not get through.

Soon, a relay system was set up around the country. Someone who answered in Missouri was asked to phone another family in Wisconsin where a passenger’s family lived.

In such a manner, almost all the passengers on the plane were able to account for themselves and their families. When the battery on the phone ran low, they charged it from a plane outlet.

Throughout the afternoon, with the pilot at an emergency meeting, the passengers were left to fend for themselves. From the windows, they could see fleets of other jets already landed on the small runway. From front to tail, Kelleher estimated there were close to 35 of the big birds on the ground. They were almost the last to land, they learned. Most of the planes after them, approaching the Canadian coast, had turned around and gone back to their European points of departure.

The hours passed. Finally, the captain returned and told the passengers that the “invasion” seemed to be limited to New York and Washington, that all the planes were now out of the sky and accounted for, and that the passengers were going to be taken off the plane. They would be processed by Canadian customs and kept in Newfoundland until further instructions were received.

The deplaning would take place in the order of arrival, bad news for the Delta Passengers. There was nothing for it but to hunker down on board, try to catch some sleep, and eat the meager remains of food that were left on board.

At 2:00 am that morning, the weary Delta Passengers finally got to alight. They were tired, hungry, and confused. They were warned not to take a single item off the plane except for the airline blanket. Kelleher had to leave his phone and his hand luggage on board, something that caused him understandable irritation.

Now they were taken by bus to a nearby hockey rink. There the passengers stood in line in the cold building while they were processed thoroughly by Canadian immigration agents. At 4:00 am, some of the passengers, including the Kellehers, were bussed to a nearby Pentecostal church to spend the night.

“They had mats on the floor, and we had to sleep shoulder to shoulder for the next six nights,” says Kelleher. “To say it was uncomfortable was an understatement.”

Many didn't even bother to try to sleep, preferring instead to watch CNN nonstop, their first images of what had really happened in New York and Washington. Kelleher remembers a stunned silence as they watched, over and over, the replay of the towers going down.

For Denis Kelleher and his family, the next few days would be a blur. They were just a few of 13,000 passengers stranded in Newfoundland, all in need of shelter and sustenance, and most varying stages of shock.

Kelleher knew from his childhood history that Newfoundland had been a major settlement for the Irish almost from the time of the first emigration to the United States. It was still a surprise to find people who had never set foot in Ireland speaking with perfect Irish accents.

Newfoundland had seen its first Irish settlers in the 17th century when ships from England called at several southern Irish ports to bring servants for the settlers who were setting up first villages on Newfoundland's icy coast. A history of the period states that most of the Irish migration at first was seasonal and that many returned. In the 1770s and 1780s, over 5,000 Irish settled there according to local history, most from Waterford, Wexford, Carlow, Kilkenny, Tipperary, and Cork.

In the 19th century, Newfoundland became a major emigration destination for Irish people. A local history compiled by Memorial University in St John’s makes clear their influence: “They [the Irish] created a distinctive subculture that is still evident. Almost all were Catholic. Many spoke Irish on arrival or distinctive varieties of English...their descendants emerged as full-fledged Newfoundlanders, a unique culture of North America.”

These Irish roots ensured that Denis Kelleher and his family, and indeed all the Irish passengers who landed in Newfoundland on September 11, received a very warm welcome.

For Kelleher, the next five days were as far removed from his busy life on Wall Street as was imaginable. “The highlight was the daily trip to WalMart, the department store, for clean underwear,” he says with a laugh.

The lowlight was trying to sleep in the cramped church with everyone lying shoulder to shoulder.

“You would just be falling asleep when someone would start snoring. I don’t think I slept more than a few hours over the entire period.”

There were other highlights though. “People invited us into their homes every night. We were told that we could shower, eat or just walk in and make ourselves comfortable. Those were wonderful people,” he says.

He also got to know his fellow passengers. “We were in such close proximity that we soon knew all about each other’s lives. We saw the best of people in tough circumstances, I can tell you that.”

On day four, just when it looked like they might get out, the tail end of a hurricane lashed the province and they were confined a further two days. Stir craziness started to set in. The waiting was the worst part, wondering if they would be kept in Newfoundland for days, weeks even, and what was happening with their families back home. Fortunately, the Canadian authorities announced on the sixth day that the air space over New York was reopening. It was a magical moment, Kelleher recalls.

Finally, after the passengers had bid farewell to their genial hosts, the Delta plane finally took off for American airspace, to the great relief of all on board. The spirit of camaraderie and friendship on board was palpable. Many have since kept in touch.

“I have 300 new friends,” Kelleher jokes.

For the Kellehers, the tale did not have a happy ending. Alex Steinman, so close that Denis considered him a surrogate son, did not make it out of the World Trade Center, despite earlier hopes.

“I gave him his first job. He was very close with my kids,” says Kelleher, his voice breaking. “It was just so senseless to lose someone like that.”

Editor’s Note: This is an extract from Niall O’Dowd’s book "Fire in the Morning" about the Irish and 9/11. Denis Kelleher died on November 22, 2019, aged 80.

Comments