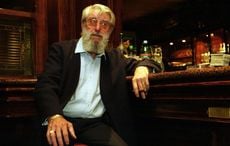

John Walsh, 104 years old and resident in Clonmel, Co. Tipperary, carries a unique distinction.

He is one of the very few people in Ireland, or indeed the world, who has seen and experienced the horrific Spanish flu of 1918 which killed at least 20,000 Irish people, and who has now lived long enough to be alive through COVID-19.

He was three years old when the deadly Spanish flu, which began in the U.S. and then spread like wildfire through Europe, arrived at his own front door. His father was struck down by it but survived.

“I was very young when the Spanish flu arrived in Clonmel,” Walsh, a former chief accountant at Bulmers, told The Irish Times in April 2020.

“Dad got the Spanish flu... My mother didn’t get the flu but I remember as he was getting better, she would let me peek in the door of his bedroom to see him.

“The warmth of his smile of welcome remains with me to this day – thankfully he survived ...”

He was one of the lucky ones. The flu, likely brought into Ireland by Irish soldiers returning from the First World War where it was rampant in the trenches, was a killer virus that spread worldwide even though there was little international travel at the time.

The first case of it was recorded on March 4, 1918, when company cook Albert Gitchell, from Haskell County, Kansas, reported sick at Fort Riley, a U.S. military facility there. Within days, 522 men at the camp had reported sick. From there it spread like lightning.

A makeshift hospital in Oakland, in 1918.

Indeed, one of the great mysteries to this day is how it seemed to explode simultaneously all over the world, even on some isolated Pacific islands.

It became known as the Spanish flu because the King of Spain was perhaps the most famous person to catch it -- he survived.

Lasting from January 1918 to December 1920, it infected 500 million people, about a quarter of the world's population at the time. The death toll is estimated to have been anywhere from 17 million to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in history.

Historian Dr. Ida Milne, whose book Stacking the Coffins: Influenza, War and Revolution in Ireland 1918-1919, deals with the impact on Ireland, estimates that 800,000 were struck down by the flu and that many deaths were unreported because hospitals were swamped and record taking was scattered at best.

The population of the entire island of Ireland at the time was about four million, which meant that 20 percent of people living on the island caught it.

It differed in one deadly way from the coronavirus, as one-fifth of those who died were young and healthy. The flu took many young men and women in their prime.

Milne writes, "What it did was silence entire communities and towns. You might see 3,000 sick in a town like, say, Dundalk, or a thousand in a town like New Ross all under medical care at the same time.”

Like today, large gatherings were fatal. A week after wild celebrations at the announcement of the end of the war the flu struck at its most deadly.

Milne says the British authorities in Ireland tried to cover up what the flu was doing.

"Right from the very beginning, secrecy is built in into the 1918 flu,” he wrote. Milne says they issued one statement that “only a Ph.D. would be able to read -- it was full of long words and difficult concepts about disease.”

As for what 104-year-old John Walsh thinks, he says the government today is doing a better job.

“I think the Irish government is doing a good job — I wouldn’t be so sure about the British,” he says.

He will be 105 in September and is hopeful coronavirus will spare him like the Spanish flu did his father. Amen to that.

*Originally published in April 2020.

Love Irish history? Share your favorite stories with other history buffs in the IrishCentral History Facebook group.

Comments