An excerpt from IrishCentral Founder Niall O’Dowd’s new book A New Ireland which tells the incredible story of how Ireland shifted from being one of the most conservative countries in the world to the most liberal.

Editor's note: On this day, April 2, 2005, Pope John Paul II, passed away. Today we remember his visit to Ireland in 1979.

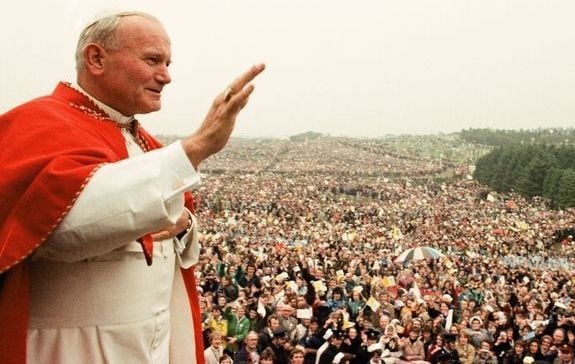

The visit by Pope John Paul II to Ireland in September of 1979 marked the high point of 1,500 years of Catholicism in the country since the time of Patrick. But even as millions turned out there were ominous signs of trouble ahead for an institution that had come to dominate Ireland more than any other European country.

If Pope John Paul II did not believe he was flying into the maw of a troubled country in September 1979, a deadly IRA operation on two fronts two weeks before he landed surely convinced him and led to speculation the trip might be canceled.

On August 26, 1979, a beautiful and sunny Irish day, a bomb exploded aboard the boat of Lord Louis Mountbatten, an uncle of Prince Phillip, a mentor to Prince Charles and a hugely popular member within the British Royal Family known within the royal circle as “Dickie.”

A New Ireland: How Europe's Most Conservative Country Became Its Most Liberal, a new book by Niall O'Dowd, now available on Amazon and at Barnes and Noble.

The bomb had been placed aboard his fishing boat, the white-and-grey-painted, 28-footer Shadow VI, at Mullaghmore Pier in Leitrim just inside the Irish Republic and a dozen miles from the border.

The question -- why such a prominent member of the royal family was fishing from a boat in the Irish Republic just a few miles away from Northern Ireland at the height of The Troubles -- was widely asked after the killing. Mountbatten obviously felt safe and had Irish police protection.

The officer on duty that day was a 25-year-old detective, Kevin Henry, who ushered Mountbatten and his party of six, including twin 14-year-old grandsons, Nicholas and Tim Knatchbull, and the twins’ maternal grandmother, Dowager Doreen Brabourne, onboard for their day of fishing and a picnic from Classiebawn Castle.

Henry’s job was done for the day, but just as he was leaving the harbor there was a large explosion, the ground shook, and an angry plume of black smoke and flame lifted toward the heavens. A 50-pound bomb had exploded under the engine placed there by the IRA during the night.

Mountbatten, one of his grandsons and a local boy who was a helper for the boat trip were killed instantly. Dowager Brabourne died the next day from her injuries. The shock bombing was followed hours later by a further IRA bombing when 18 British soldiers were killed in an ambush in Warrenpoint, Co. Down.

Tensions ran very high. Suddenly there were fears for the pope’s safety that Protestant militants might try and take him out in an act of revenge. A trip to Northern Ireland with Mass at the cathedral in Armagh had to be scrapped, much to the pope’s private secretary Monsignor John Magee’s chagrin. He would not get the pope to cross the border after all.

Instead, a very surprised, prosperous Irish farmer with massive land outside the town of Drogheda but in the Archdiocese of Armagh had his farm rented for the day by the Catholic Church. He was told a crowd of 40,000 -- the estimate was incorrect by 250,000.

A few weeks before the news became definite that the pope was coming, workmen in 24-hour non-stop shifts built a 135-foot tall cross in Phoenix Park, Europe’s largest open space. It later turned out it was constructed without planning approval or any oversight of the planning authorities, but who was going to stop a giant cross for a great pope? “The pope is coming” hysteria spread throughout Ireland, creating a bedlam of frantic preparations including a moral crusade to sanctify the souls of the Irish prior to his arrival began.

In an absurd moment befitting the comedians involved, The Life of Brian, a Monty Python film satire about a man mistaken for Jesus, was banned by censor Frank Hall who uttered the incredible ruling was because it “made Christians and Jews look like awful gobshites.” He was said to be especially upset by the scene when the Monty Python cast mistake “blessed are the peacemakers” for “blessed are the cheesemakers.”

Even one of the movie’s satirical songs, “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life,” fell under the censor’s pen. Ireland was going to be both good and holy for the papal visit.

When he arrived, fittingly on the Aer Lingus jet named St. Patrick, the pope strode off the plane, blessed the Irish people, and dropped to his knees to kiss the ground. Not since a young president named John F. Kennedy in the summer of 1963 had visited Ireland was there a similar momentous occasion when the nation flew its brightest colors.

The great and good of Ireland were waiting in serried ranks. It fell to the Irish President Paddy Hillery to escort His Holiness.

There had been rumors for years of a Hillery mistress, or maybe two or three. As the Irish Independent reported, “These rumors went on for months in 1979, in the run-up to the papal visit here. They were so persistent and pervasive that the then Taoiseach Jack Lynch advised Mr. Hillery that he had to deal with the situation.”

This came to a head when the editors of the national newspapers and the head of news in RTÉ were summoned to the Aras, Hillery’s official residence, where he denied a story that had not been published anywhere, completely confusing the public at large who knew nothing about the inside gossip.

Either way, in order to escort the pope, Paddy Hillery would have to be without sin, and he insisted that the rumors were completely false and that he would not be resigning, thereby gaining absolution. The sensational story was international news.

The pope thus began his whirlwind journey around Ireland by shaking hands with a beleaguered president.

The reception for Il Papa was incredible. Estimates of crowd figures were staggering. About 2.7 million people turned out to welcome the pontiff at six venues: Dublin, Drogheda, Offaly, Kildare Galway, Limerick, and Knock.

New York-based Irish journalist Cahir O’Doherty, who saw the pope in Mayo, remembers the countrywide hysteria, “It was as though The Beatles and Jesus had arrived together to play a concert,” he said. “It was mass hysteria; it was unprecedented. It was morning in Ireland.”

Deirdre Falvey, now an Irish Times writer, was a schoolgirl at the time:

“I remember trekking through fields at night to our designated pen. The wait for hours in the dark and cold was long but it was exciting to be out and about in the middle of the night among thousands arriving in the dark. By the time Mass started, we were tired but the infamous double-act (abusers Father Cleary and Bishop Eamonn Casey) whipped up excitement. The man himself was on a distant platform, and between the echoey PA and the accent, I barely heard what he said. Still, we roared and cheered and were thrilled: the hysteria and the crowds were like a rock concert.”

Nuala McCann from Northern Ireland wrote for the BBC years later what she remembered:

“Up at dawn and on our way to the wild fields of Galway to Ballybrit racecourse where thousands of young people had gathered to get a glimpse of this man. There, on the stage, Bishop Eamonn Casey and Father Michael Cleary whipped up the crowd. ‘Listen, listen…Is that a helicopter, I hear?’ and we all cheered and roared and sang ‘By the Rivers of Babylon’ jumping about in the icy field, wishing we had remembered to go to the toilet. Then, suddenly, he was among us. He told us in endearing English, heavy with a Polish accent, that he loved us. “Young people of Ireland, I lof you,” he said -- and we cheered wildly and tried to get within distance of the popemobile as he headed out among the crowds.”

Damian Corless, a papal steward for the day, remembers how high the stakes were: “Young Irish Catholics for a decade had been lapsing at a rate of knots, but generally not in favor of godlessness or open hostility to the Mother Church. Instead, many were shopping around for new beliefs and it was a boom time for maharishis, swamis, and a host of eastern and Christian offshoots. …”

When you take into consideration the population of the Republic was 3,368,217 in 1979, the numbers were incredible. More than one million people from all over Ireland and some cities in England attended the first-ever papal Mass in Ireland’s Dublin’s Phoenix Park.

Afterward, he traveled to that huge private farm outside Drogheda, where 300,000 people, many from Northern Ireland, had gathered. There the pope made his most significant speech when appealed to the men of violence: “On my knees, I beg you to turn away from the path of violence and return to the ways of peace.”

Listening was a Belfast Redemptorist priest based in West Belfast at the core of The Troubles. Father Alec Reid was prompted by the pope and his own sheer revulsion at the violence to begin an extraordinary peace mission that grew into the Irish peace process that ended the violence with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998.

Amazingly, three years later, Father Reid, on a much-needed break from his peace work, was in St. Peter’s Square on May 13, 1981, when there was an assassination attempt on the pope’s life that occurred just after the popemobile had passed him by.

Pope John Paul began the second day of his tour with a short visit to the ancient monastery at Clonmacnoise in Co. Offaly. Later that morning he celebrated a Youth Mass for 300,000 at the racetrack in Galway. It was here that the Pope uttered perhaps the most memorable line of his visit: “Young people of Ireland, I love you.”

The Irish visit by Pope John Paul II was destined to dwarf the crowds for the Eucharistic Congress in 1932 and prove that the “Faith of our Fathers” was just as strong in the new generation.

In Galway, hundreds of thousands of young people chanted, “We love the Pope.” As the Irish Independent reported, at one point “the swaying and ecstatic gathering broke into song with ‘He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands,’ symbolizing their feelings of love of Christ’s Vicar on earth.”

As Independent newspaper reporter Kim Bielenberg noted: “The song title was used as the banner headline across the front page of the Irish Independent on the following day, summing up perfectly the rapturous mood of the visit.”

It was the Irish Catholic Woodstock, presided over by two deviant clerics whose names would eventually become notorious. Bishop Casey and Father Cleary led the anthem calls and roused the young to fever pitch.

The Irish Independent report focused on the music festival atmosphere: “Woodstock, the Isle of Wight, and all the Ballisodares (an Irish festival) one could imagine could not give the right impression of volume and enthusiasm in Ballybrit yesterday.”

As Bielenberg pointed out, the church was in its prime still in terms of its influence:

“At the time, church teaching was powerful enough to ensure that certain key doctrines dominated the political sphere. Seven years after the visit, traditionalists wielded their power by ensuring that attempts to introduce divorce were defeated in a referendum. In 1983, they also introduced the eighth amendment to the constitution, banning abortion. On those autumn days in 1979, the façade of the church looked secure and stable, but inside the structure was already crumbling.”

The Irish Independent, using language that was incredibly devout, editorialized: “The 59-year-old Polish Pontiff is coming to ensure that Ireland remains faithful. …”

In retrospect, Irish American history professor James Donnelly of the University of Madison, Wisconsin, said the red lights were flashing despite the adulation for the pope. “Apart from conferring certain limited short-term benefits, the papal visit did not, in fact, better equip the Catholic Church in Ireland to deal effectively with its challenges and problems,” he said.

Such sober analysis may be history’s verdict on the papal visit, but for those who were there, it became almost hysterical at times, including for the VIPs. But it was not just the ordinary folk who became overexcited. A papal steward at the event, speaking anonymously, remembers amazing occurrences right after the Phoenix Park Mass:

“I had made my way back up to the altar when there was a sudden commotion nearby. I turned and was amazed to see Pope John Paul II himself, struggling to make his way through an admiring, enthusiastic group of cardinals, ambassadors, and various dignitaries.

“Suddenly I felt a hard clout on my shoulder. Surprised, I wheeled around indignantly to see who it was that had delivered such an uncalled-for whack. There, standing behind me was Dublin Archbishop Dermot Ryan. Before I could utter a single word he shouted at me, ‘Get up there and help that man!’ -- that man being His Holiness the Pope. Without any further encouragement, I ran up to where His Holiness was and linked arms with other volunteers.

“We surrounded the pope, protecting him from the admiring mob of dignitaries. Together, we were able to escort John Paul off the altar into his rooms. The next time I saw him, he was on route to his helicopter, on his way out of the Phoenix Park and onwards in his pilgrimage to Ireland.”

The Irish Times reported:

“Dublin events alone required a mammoth amount of equipment, including various fittings, banners, piping, benches (about two thousand), tarps, tents, chairs, signage, plywood sheeting, stakes, tables, and about 800 umbrellas. The latter were specially ordered for visiting archbishops and bishops, only to go unopened as the nice weather made them an unnecessary expense.”

When the crowds left, it all had to be dispersed somewhere. As The Irish Times explained, it was auctioned off by the church in a series of bargain auctions held. The auction the Times reporter attended on a freezing cold day the following winter was a sight to behold:

“A whole line of gentlemen was standing on a bench stamping their feet to keep the blood moving, when the bench collapsed and the man with the dozen umbrellas at £1.50 apiece, the man with the six slightly damaged communion trays, and the man with the roll of red carpet at £2 a yard, all crashed to the frozen mud floor.

“Des Kelly, who fitted the carpet, was there to buy it back in large quantities at £1 a yard – to sell it again. … [and that] Tony Curran wanted carpets, too. ‘I’m going to make an overcoat with ‘the pope walked on this’ printed on the back.’”

The country had gone certifiably crazy for the pope, and the immediate impact was full churches, deep expressions of devotion, and thousands of male children called John Paul. It was the high-water mark of 1,500 years of Catholicism.

* A New Ireland, by Niall O’Dowd, is available on Amazon.com and Barnes & Noble.

Comments