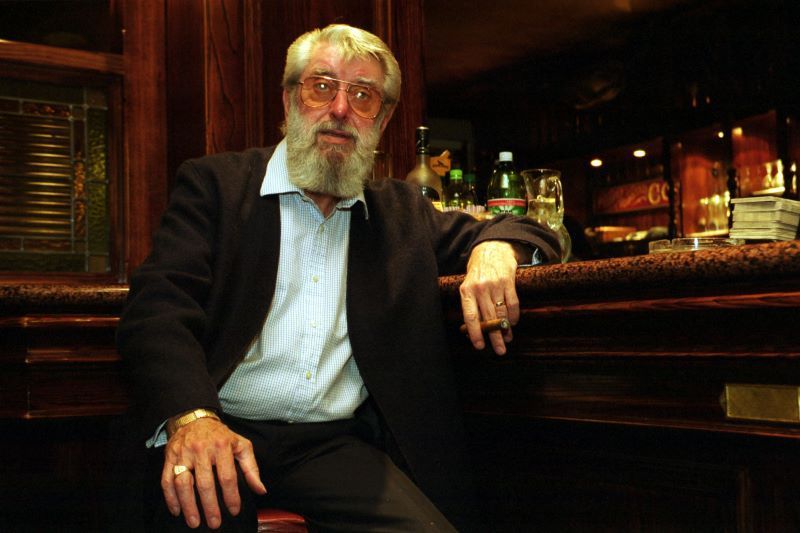

| Shane MacGowan |

The death of a newspaper, especially in these tough economic times, is always a source of deep regret, but the closure of the Irish Post in England is a truly awful event.

The announcement that Britain’s leading Irish newspaper was about to close down was a shock to the system. How at a time when tens of thousands of Irish are streaming into Britain again could their main newspaper be closing?

I don’t know the answer to that question, but its closure is a tragedy for the Irish community in Britain.

I can only imagine what the Irish Post founder, the late Brendan Mac Lua, would make of what has happened to his brainchild, I speak personally here.

Mac Lua provided much of the capital for the start up of Irish America magazine, was an investor in the Irish Voice and was a hugely encouraging friend to me in those early days of Irish American publishing.

I returned the favor for him years later by introducing him to the Jefferson Smurfit Company, which subsequently bought the Post and then sold it on to the Irish Examiner, the company that was managing the paper when it closed down last week.

Mac Lua established the Irish Post in 1970 in the teeth of rampant anti-Irish sentiment in England, mostly brought about by IRA bombings and a spate of comedians making Irish people the butt of all their jokes.

_______________

Read More:

Irish Post newspaper goes into liquidation

Major Irish newspaper Star on Sunday goes bust

Kerry's 'Kingdom' newspaper closes with loss of 11 jobs

Receiver appointed to the Sunday Tribune newspaper

________________

Mac Lua was fearless, however. He was so effective in standing up for the Irish that the Irish government of all people started a newspaper trying to close him down. It quickly failed.

His advocacy on behalf of the Guildford Four and the Birmingham Six, and his outspoken statements on shoot to kill policies in Northern Ireland, were all regarded by Irish governments at the time as being highly inconvenient, as they tried to forge an united front with the British government against Irish Republicans who they saw as the root of all evil.

The government was mistaken in that belief as Mac Lua pointed out, and he was more than vindicated by the Irish peace process and how enlightened Irish leaders such as Albert Reynolds forged alliances with Irish Republicans and the Irish diaspora to help bring about peace.

But the Post was much more than about politics. It covered a vast and sprawling Irish community from Glasgow to Cornwall and wrote about their local activities, dances, fundraisers, sports events and community happenings.

The Post was the vital hub of the Irish community when I lived in Britain during the 1970s, an eagerly awaited weekly insight into the happenings in the community that was a vital lifeline for so many.

Mac Lua also forged a relationship with then Greater London Council leader Ken Livingston, who ensured that Irish cultural activities received funding same as any other ethnic group.

That was a massive breakthrough, and allowed the Irish community to show how important and deep their historical ties to Britain were.

When you think of the Irish in Britain you have to think of Shane MacGowan, Martin McDonagh and the Gallagher brothers of Oasis as just a few examples of how deeply influenced young Irish in Britain were by their Irish/English roots.

The survival of that community as a cohesive group is threatened by the downfall of the Post. It is a sad end to a publication that saved a community and allowed them to embrace their Irishness.

Comments